His father's reputation

Little is known about Thomas Cromwell’s early life and family, but legal records provide us with some insights. Mantel opens her novel Wolf Hall (2009) with Walter Cromwell, Thomas’s father, beating the young Thomas. But Walter’s notoriety is largely the product of misunderstanding the records.

Resident in Putney, Walter gained a reputation for minor infractions of the law, including watering his ale and running his animals on the common. While he certainly was fined at local courts for brawling and other misdemeanours, he still rose to the level of yeoman and was able to lend money and act as guarantor for others seeking credit.

Misconceptions about the severity and extent of his crimes were begun by John Phillips, an engineer (not a professional historian), who lived in Putney and published two articles on Walter in the 1860s. Phillips’ misrepresentations have been spread by historians but are largely incorrect.

While Walter possibly operated a smith in Putney, the records show he definitely brewed beer and became relatively wealthy.

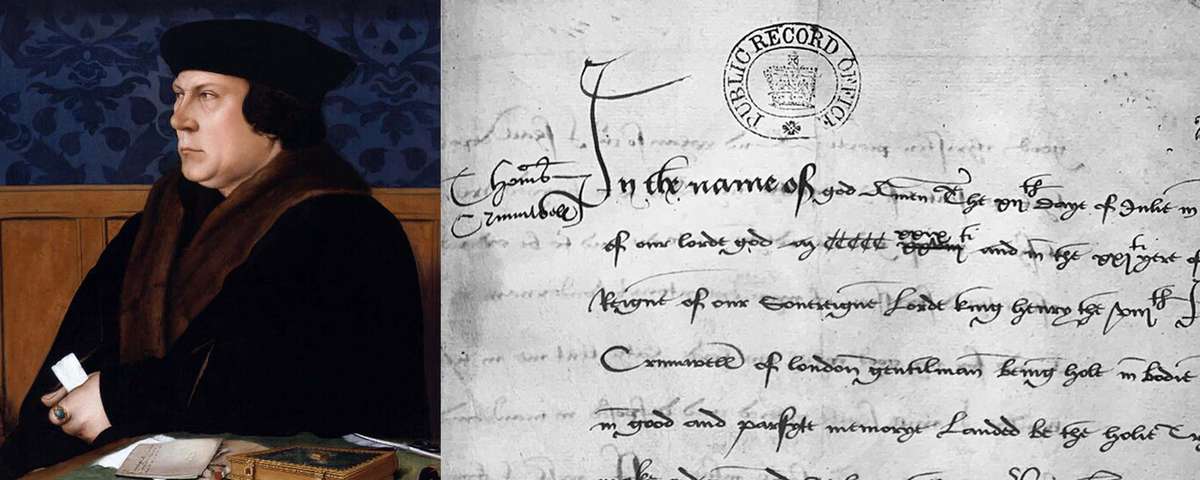

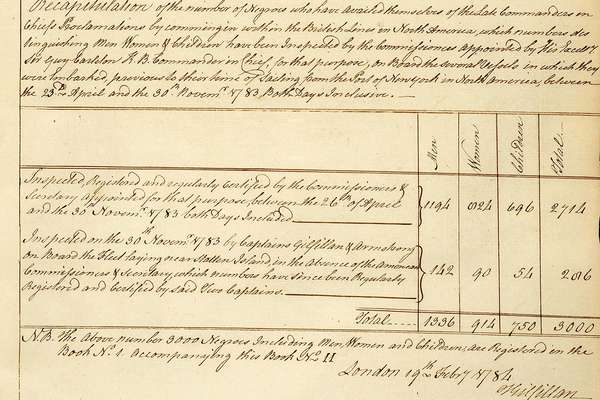

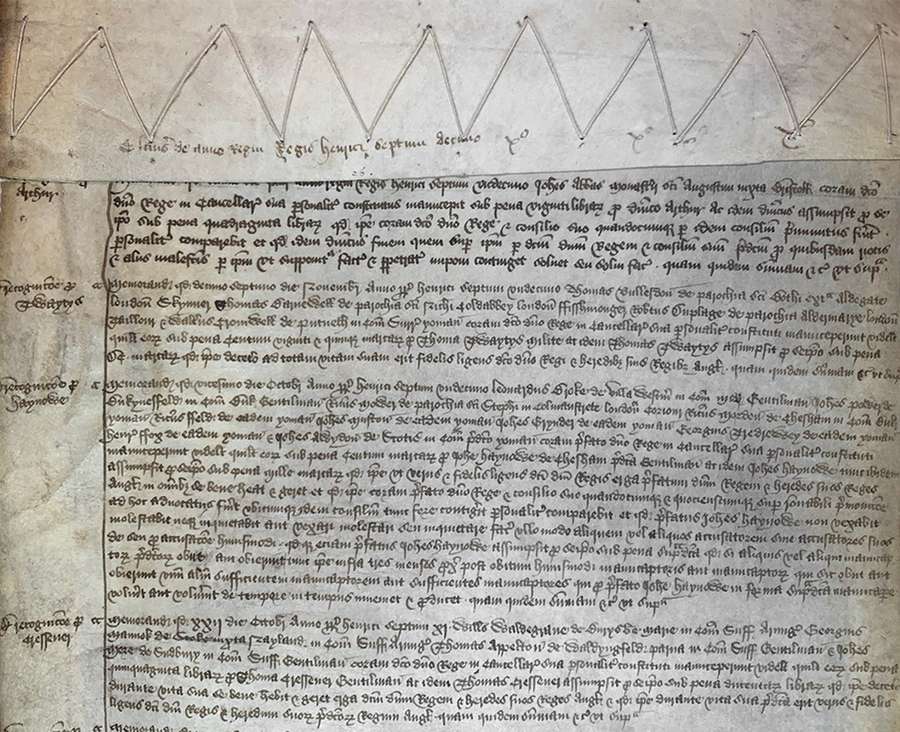

Close roll mentioning Thomas Cromwell’s father Walter, 17 November 1495. Catalogue reference: C 54/376, m. 19. 10 Henry VII

Walter appears in this Close Roll – a type of document containing private, often important, instructions – dated 17 November 1495. It describes his involvement in a bond for 125 marks, promising the lifelong loyalty of Sir Thomas Thwaites, ex-treasurer of Calais and resident of Barnes. Thwaites had been found guilty of involvement in Perkin Warbeck’s plot to overthrow King Henry VII, but had been spared death.

Walter, here described as a yeoman, has links to London merchants and to a former high officer in Calais. This strongly suggests he had the means to educate his son, and potentially a broad network to introduce him to. Thomas may have been able to make good use of these contacts in Calais and the Low Countries when he began his career as a merchant around the year 1512.

The cardinal’s man

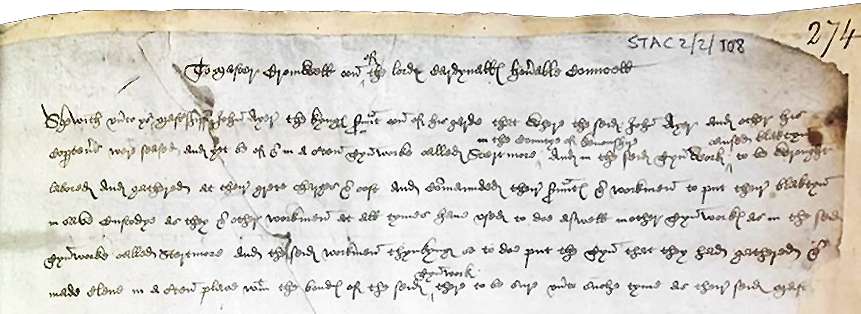

Thomas began his political career as one of Cardinal Wolsey’s servants in the 1520s. He was elected an MP to the House of Commons in 1523 and by the end of the decade he was publicly acknowledged as the cardinal’s man, as demonstrated in the bill of complaint addressed to ‘Master Cromwell of the Cardinal’s Counsell’. It was submitted to Star Chamber, the judicial arm of the Privy Council, a powerful body that advises the monarch.

Proceedings of the Court of Star Chamber, Ayer v Langifford, including bill written to Cromwell. Catalogue reference: STAC 2/2/108

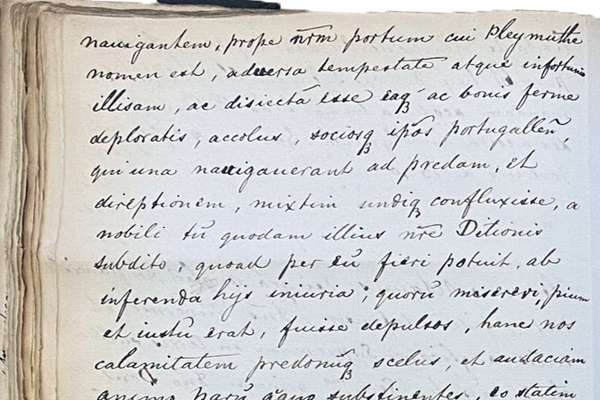

Henry VIII was a fickle master and Cardinal Wolsey eventually fell out of favour, having been unable to secure a papal annulment for Henry’s marriage to Queen Katherine. It is probably no coincidence that Cromwell made his will at this time, which has survived in the State Papers, an extraordinary collection of bound volumes of correspondence and other material that runs from 1509–1782.

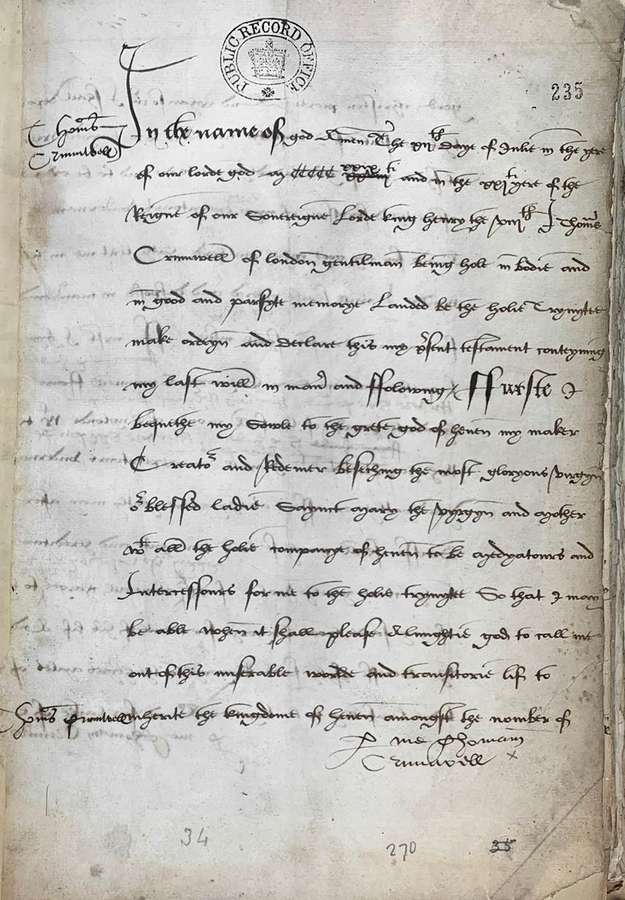

Thomas Cromwell’s will

In the name of God Amen The xiith daye of Julie in the yere

of our Lorde god mcccccxix and in the xxith yere of the

Reigne of our Sovereigne Lorde king henry the viiith I Thom[as]

Crumwell of london gentilman being hole in bodie and

in good and parfyct memorye Lauded by the holie trynytie

make ordeyn and declare this pr[e]sent testament conteyning

my last will in man[ne]r and following ffurste I

bequethe my sowle to the grete god of heven my maker

Creator and Redemer beseching the most gloryous virgyn

O[u]r blessed ladie saynt Mary the vyrgyn and mother

wth all the holie companye of heven to be medyatours and

Intercessors for me to the holie trynytee so that I may

be able when it shall please Almightie god to call

out of this miserable worlde and transitory life to

inherite the kingdome of heven amongst the number

p[er] me Thomas

Crumwell

Excerpt from Thomas Cromwell’s will, originally written on 12 July 1529 and periodically updated thereafter. Catalogue reference: SP 1/54, ff 235–44

As you can see here, Cromwell signed the bottom of each page of his will. This was a living document in Thomas’ lifetime and – rather poignantly – he had to update it several times as two of his children, Anne and Grace, died in their early childhood.

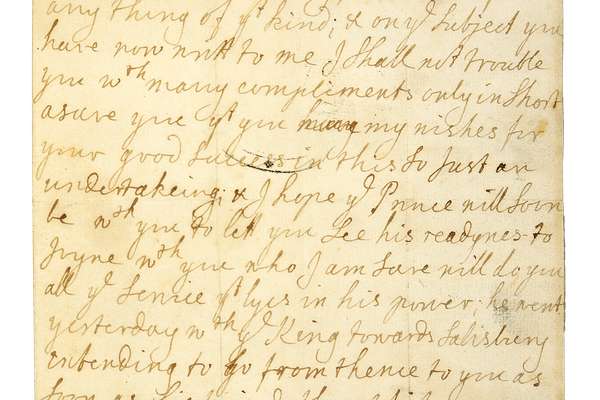

Wolsey’s dismissal from office by Henry left Cromwell exposed to Wolsey’s political enemies, who now became his own. In this letter, also contained in the State Papers, Thomas’ friend Stephen Vaughan writes that he had heard the news of the cardinal’s ‘overthrow’ but sought to reassure Thomas:

‘You are more hated for your master’s sake than for any thing which I think you have wrongfully done against any man.’

Stephen Vaughan to Thomas Cromwell, 30 October 1529. Catalogue reference: SP 1/55, f. 198

Earning the king’s trust

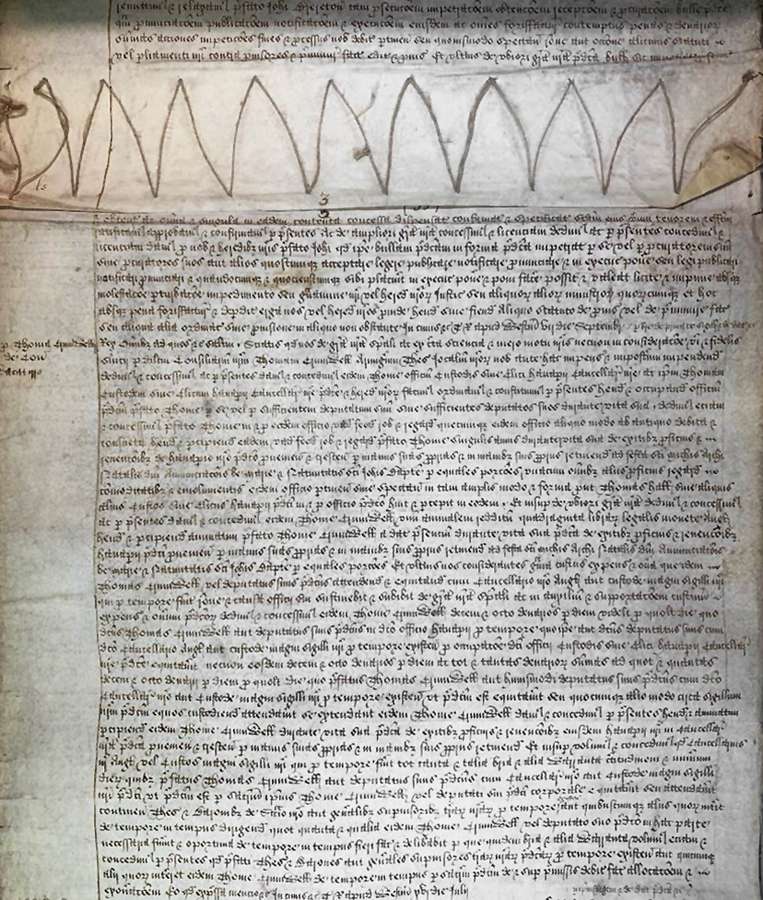

After the cardinal’s fall, Thomas moved into royal service. The document below records his appointment in July 1532 as Clerk of the Hanaper in Chancery, one of the most powerful courts in the land. The role gave him oversight of all of Chancery’s workings (as well as an opportunity to collect the fees it charged).

The document is a 'letter patent'. Like Close Rolls, letters patent were issued by the crown and enrolled on parchment, but this time the contents were public – here, announcing a promotion.

Patent roll showing the letter appointing Cromwell to royal service, 3 July 1532. Catalogue reference: C 66/660

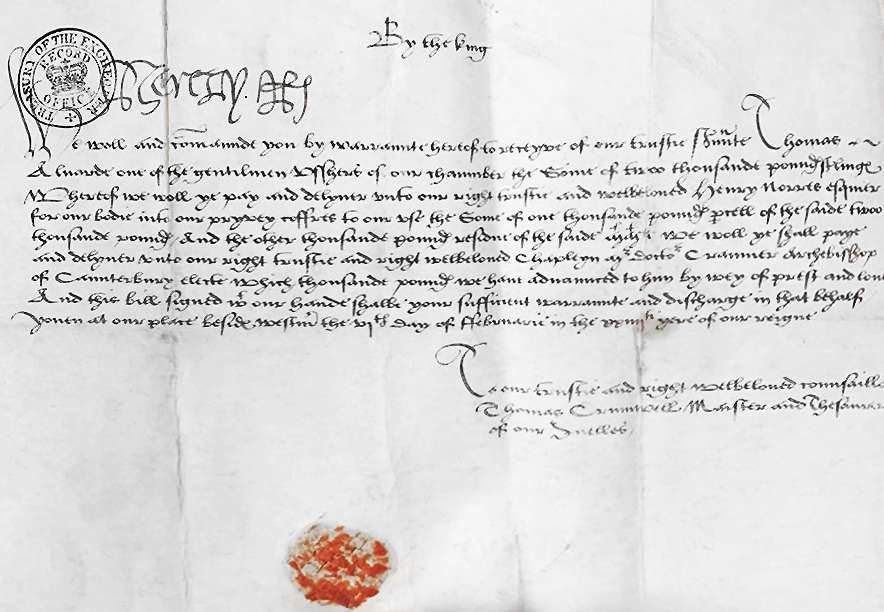

Thomas had evidently won the king’s trust by 1532 and was also appointed the Master of the Jewel House. In this document, we can see Thomas performing his duty, receiving a warrant (an order) from the Exchequer to organise a loan of £1,000. The money was for the archbishop-elect of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, to purchase a papal bull (an official decree from the Catholic Church) confirming his appointment. Henry VIII’s stamped signature is at the top left.

Warrants relating to Cromwell’s work as Master of the Jewels, 6 February 1533. Catalogue reference: E 101/421/9

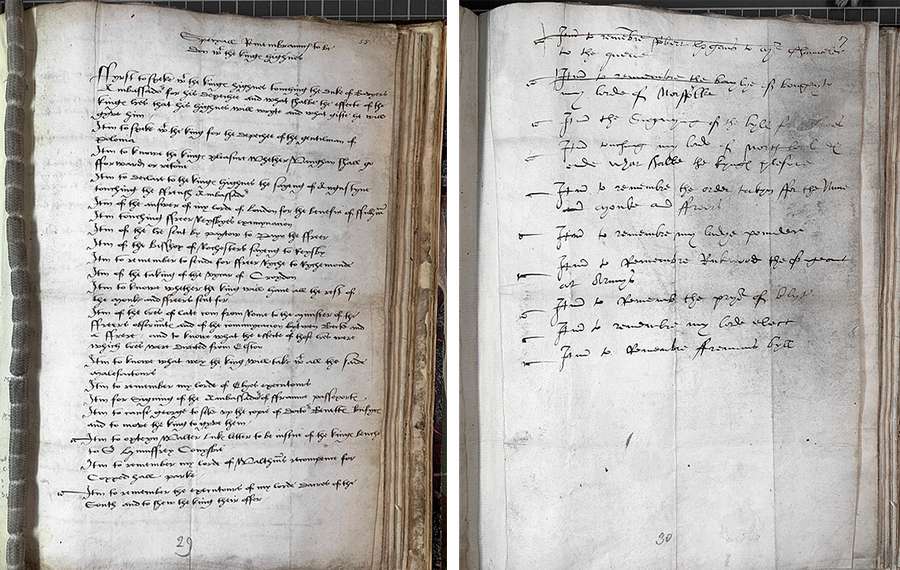

We have Cromwell's notebooks, which offer a wonderful insight into his work at this time. In the one below, he had a clerk make notes for the day's business with the king, before Thomas himself took the notebook and made additional notes or deletions. Thomas' handwriting is visibly hurried in comparison with the first page, where the clerk has carefully noted the business, possibly having been dictated by Thomas.

Thomas Cromwell’s 'Notebooks': a collection of his papers spanning the 1530s, including some of Wolsey’s papers. Catalogue reference: E 36/143

The Act of Supremacy

Wolsey’s failure to secure an annulment of Henry’s marriage to Queen Katherine created an opportunity for religious reformers to exploit. They sought to use the king’s frustrations with the papacy to have Henry declare himself the Supreme Head of the Church of England, instead of the pope. This monumental move was secured through parliament in 1534. The Act of Supremacy, though short, has had enormous consequences for the people of Britain and Ireland since the sixteenth century.

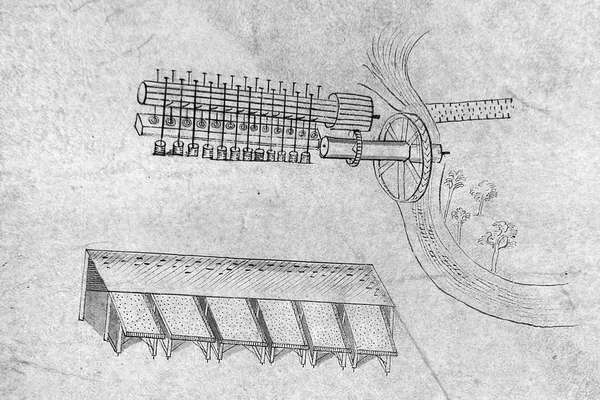

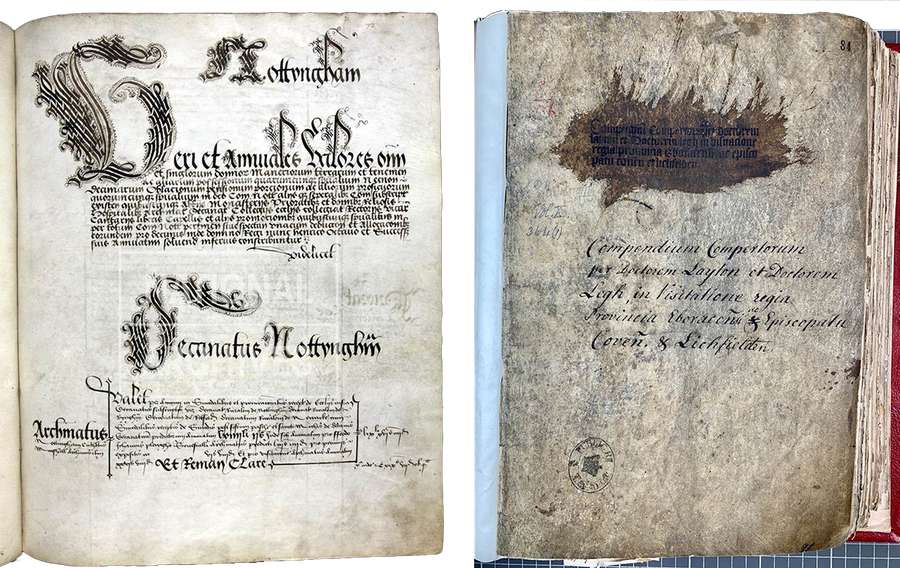

Religious reformers such as Cromwell wished to target the wealth of the church in England, specifically that held by the monasteries and religious houses. From 1534 the government pursued a policy of confiscation. Cromwell was a tireless administrator who carefully assessed the value and wealth of each establishment, and compiled it all for the king in a survey called the Valor Ecclesiasticus (‘valuation of the church’).

To justify confiscating it, Cromwell collected sordid accounts of clerical abuses during a series of visitations in 1535–6, collated in a document called the Compendium Compertorum ('collection of findings').

Left: Page from the Valor Ecclesiasticus. Catalogue reference: E 344/22, f. 72. Right: Page from the Compendium Compertorum. Catalogue reference: SP 1/102

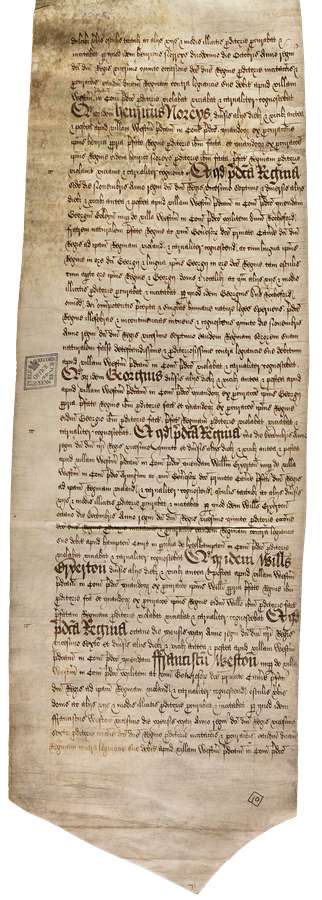

Accusation against Anne

Anne Boleyn forms a central part of the Thomas Cromwell story, and he of hers. Having been unable to produce a male heir for the king, Henry sought her removal. By 1536 the uneasy alliance that had existed between Anne and Cromwell broke down, and he facilitated her downfall by setting up charges against her, including of having had affairs with her courtiers and her brother. Anne was arrested and accused of treason.

A remarkable account of these days survives in a letter gifted to Queen Elizabeth I, Anne and Henry’s daughter, in 1558. In it, a supposed eyewitness recounted to Elizabeth his recollections of having witnessed Henry learn about the allegations against Anne. They were at Greenwich Palace at the time and courtiers witnessed the king's anger and Anne's shock at what was alleged. The account describes how Anne was holding the infant Elizabeth in her arms, pleading with Henry. Of course, this may have been an embellishment to win the new queen's favour.

The charges against Anne Boleyn, her brother and other courtier. Catalogue reference: KB 8/9

The charges stuck and a special court was established under the authority of the Court of King's Bench to try the queen, presided over by her uncle, Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk. The charges against Anne were read out and she failed to overturn them, so her fate was sealed. She was convicted and executed.

Though this moment may have marked the high point of his power and influence, within just a few years, Cromwell himself would meet the same fate.

Cromwell's downfall

When it came, Cromwell’s undoing was swift. Having promoted and secured Henry VIII’s marriage to Anna of Cleves, the king’s lack of interest in his bride created an increasingly perilous situation for Cromwell.

Although it was hidden from all but the closest advisors for several months in 1540, Henry’s inability to consummate the marriage was both humiliating for him and dangerous for Cromwell, as he would have to explain to the world why the marriage was to be cancelled.

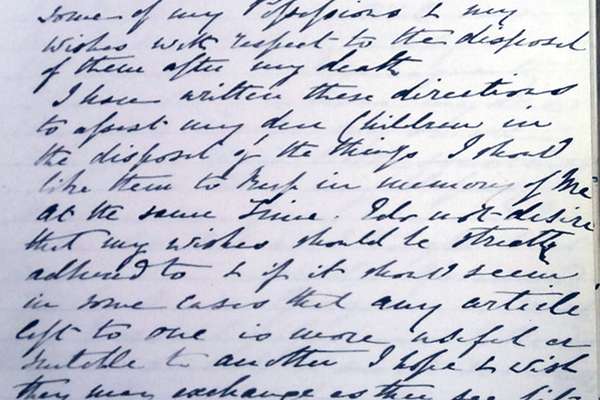

The pressure grew on Cromwell, and Thomas’ enemies now saw an opportunity to unseat him. Although elevated to the earldoms of Essex and Oxford in April 1540, by June he was arrested at the privy council, stripped of his honours and titles, and charged with both heresy and treason. He was attainted by parliament while imprisoned in the Tower of London, where he was executed on 28 July, the same day that Henry married Katherine Howard.

... your Majesty now of late hath found [...] the said Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex, contrary to the singular trust and confidence which your Majesty had in him, to be the most false and corrupt Traitor, Deceiver, and Circumventor against your most Royal Person, and the Imperial Crown of this your Realm, that hath been known, seen, or heard of in all the time of your most noble Reign.

Thomas Cromwell's Act of Attainder. Parliamentary Archives: Private Act, 32 Henry VIII, c. 62

Most of Cromwell's letters were lost. He had used an exact archival system for his correspondence, with clerks copying outgoing letters and carefully filing incoming ones. But copies of Cromwell's outgoing letters were likely destroyed by his staff upon his arrest.

Many documents from the Tudor period have not survived, but hundreds of thousands remain. Important insights into lives like Thomas Cromwell's, both personal and professional, can be uncovered in records at The National Archives. Through them, historians can attempt to interpret and explain this complex and tumultuous era.

Records featured in this article

-

- From our collection

- C 54/376

- Title

- Close roll mentioning Thomas Cromwell’s father Walter

- Date

- 1495

-

- From our collection

- STAC 2/2/108

- Title

- Proceedings of the Court of Star Chamber, mentioning Cromwell

- Date

- 1519–1520

-

- From our collection

- SP 1/54

- Title

- Thomas Cromwell’s will

- Date

- 1529

-

- From our collection

- C 66/660

- Title

- Patent roll including the letter appointing Cromwell to royal service

- Date

- 1532

-

- From our collection

- E 101/421/9

- Title

- Warrants relating to Cromwell’s work as Master of the Jewels

- Date

- 1533

-

- From our collection

- E 344/22

- Title

- Returns of the Valor Ecclesiasticus

- Date

- 1535

-

- From our collection

- SP 1/102

- Title

- The Compendium Compertorum

- Date

- 1536

-

- From our collection

- KB 8/9

- Title

- Charges against Anne Boleyn, her brother and other courtiers

- Date

- 1536