Record revealed

The first American invention to obtain an English patent

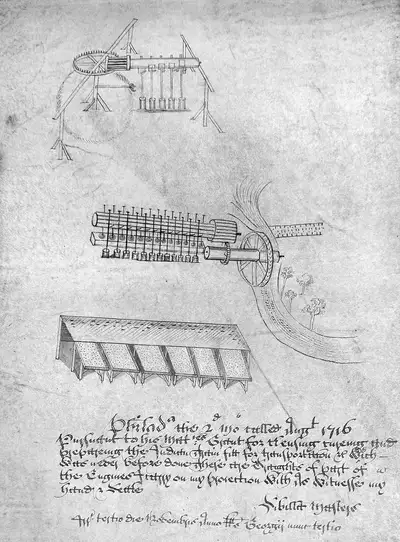

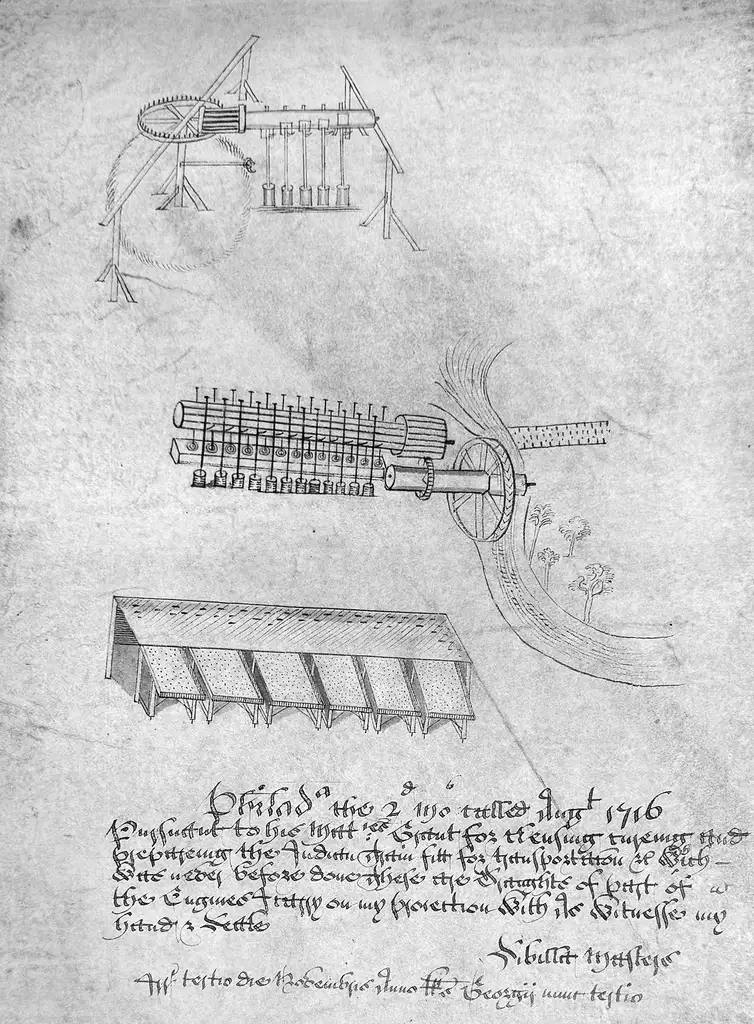

Sybilla Masters (around 1670s – 1720) submitted these drawings in the final stage of securing a patent for machinery for 'cleaning and curing Indian corn'. They made her the first person living in the American colonies to obtain an English patent for an invention.

Images

Image 1 of 1

Sybilla Masters, drawings for an invention for 'cleaning and curing Indian corn'.

Transcript

Philadelphia, the 2nd day of the 6th month called August 1716.

Pursuant to his Majesties Grant for cleansing, curing and preparing the Indian Grain fitt for transportation & Which was never before done these are draughts of part of the Engines I testify on my protection With the Witnesse my hand and Seale

SIBILLA MASTERS

In tertio die Novembris Anno MDCCXVI Georgij anno tertio

Why this record matters

- Date

- 1716

- Catalogue reference

- SP 34/21/43

Sybilla Masters was a Quaker woman who lived in Philadelphia, in the British Province of Pennsylvania. Little is known about Sybilla's early life. Her father was a merchant and mariner and her husband, Thomas, who may have come from Bermuda, was a successful merchant who served in official posts in Pennsylvania, including two terms as mayor. Pennsylvania was a key site for early Quaker settlers after William Penn designated it as a refuge from religious persecution when he founded the colony in 1681.

Corn, referred to in this record as 'Indian grain', was an important crop for early settlers in the North American colonies. This record shows three drawings that illustrate a process for cleaning and curing corn in which a series of hammers attached to an engine were used to beat the corn kernels repeatedly to shell and grind them. This action could be powered either by a wheel turned by an animal, as shown in the first drawing, or by water, as in the second.

This method mechanically replicated the process used by indigenous women, who beat corn by hand with a mortar-like tool to grind it and make it into hominy meal, a staple of the local diet.

Sybilla had plans to export hominy meal and attempted to market it as a health food, claiming it could offer relief from tuberculosis. She branded the product 'Tuscarora rice' seemingly after the Tuscarora, an indigenous people of North Carolina, although it is not clear whether she had any direct connection with them.

Although some of the early colonies had established their own patent laws and protections, in 1712 Pennsylvania was not yet one of them. Demonstrating considerable determination, Sybilla sailed to England to petition for a patent under English law which granted exclusive rights to make an invention and profit from it for a period of 14 years.

This was a complicated, time-consuming and expensive process and involved navigating a labyrinth of government offices and courts. Sybilla described her efforts in a petition in 1713:

'I have been at great trouble, expence, and have ventured my life across the seas […] I have left my country, my family and all your comforts of life for the good of the publick' […] I have spent seven years and vast sums and still must more'.

At this time, married women could not own property, participate in trade, or sign contracts in their own name, so the patent was granted to her husband, Thomas Masters. Despite this, the wording of the grant to Thomas acknowledges that this was a 'new invention found out by Sybilla, his wife.'

In 1716, she was able to return home to Philadelphia with her patent secured, becoming the first American in the colonies to do so. Thomas had purchased a mill and there is evidence that it was in operation, although 'Tuscarora rice' never achieved success in the English market. Sybilla passed away in 1720, just four years later.