Record revealed

The Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS)

The first Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea was prompted by the sinking of RMS Titanic. An attempt to establish basic rules became the most important international treaty about the safety of merchant ships and sea travel.

Images

Image 1 of 3

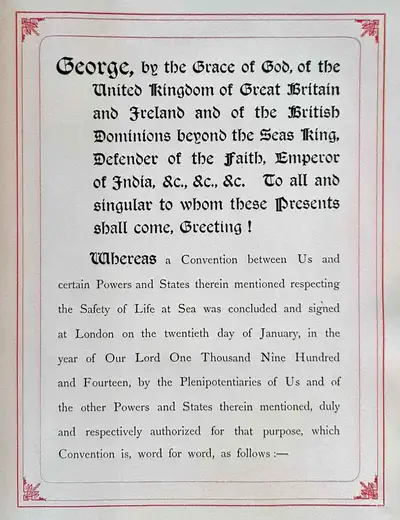

The first page of the British ratification of the 1914 Convention.

Transcript

George, by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and of the British Dominions beyond the Seas King, Defender of the Faith, Emperor of India, &c., &c., &c. To all and singular to whom these Presents shall come, Greeting !

Whereas a Convention between Us and certain Powers and States therein mentioned respecting the Safety of Life at Sea was concluded and signed at London on the twentieth day of January, in the year of Our Lord One Thousand Nine Hundred and Fourteen, by the Plenipotentiaries of Us and of the other Powers and States therein mentioned, duly and respectively authorized for that purpose, which Convention is, word for word, as follows :—

Image 2 of 3

Note signed by the Foreign Secretary stating that adhering to the Convention might not be possible until after the First World War.

Transcript

The undersigned, His Britannic Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, in depositing the Ratification of His Britannic Majesty of the International Convention respecting the Safety of Life at Sea, signed at London on January 20, 1914, hereby declares that His Britannic Majesty's Government reserve to themselves the right, in case of necessity, to defer taking steps to enforce certain of its provisions until after the cessation of the present hostilities.

Done at London, the Thirtieth day of December, 1914.

E Grey.

Image 3 of 3

The back of the seal, in red sealing wax with seal tassels of silver bullion.

Why this record matters

- Date

- 30 December 1914

- Catalogue reference

- FO 94/999

As a result of the sinking of RMS Titanic in 1912, delegates from 13 different countries and their associated colonies assembled in London between 23 November 1913 and 20 January 1914 to establish international standards in shipping safety.

The conference was divided into six committees, which looked at the safety aspects relating to radiotelegraphy, shipping design and construction, safe shipping lanes, ice warnings, life-saving routines and appliances, ice patrols and distress signalling.

The British delegation was headed by John Charles Bingham, Lord Mersey, who had headed the British Board of Trade enquiry into the sinking of RMS Titanic, and who would go on to do so for the official enquiries into the sinking of RMS Lusitania, and RMS Empress of Ireland.

The original convention consists of eight chapters covering 73 articles. Among these:

- An international ice patrol was to be set up to warn ships of the presence of icebergs, to destroy dangerous icebergs or ‘derelicts’, and to recommend safe routes to avoid them.

- Companies were obliged to publish the routes of their vessels, and owners were compelled to follow routes established by the large shipping firms.

- Ships had to be fitted with a radiotelegraph and all first- and second-class ships had to maintain continuous radio watches. Appendices formalised international distress codes and Morse codes.

- Inspections became mandatory during construction and regularly afterwards to ensure that all ships reached safety requirements regarding build, efficiency, and maintenance, requiring certification each year.

- Both lifeboats and lifejackets were required for everybody on board, including passengers and crew. Lifeboats were to be easily launched and of sufficient strength to be safely lowered into the water when full.

- Each member of crew was to be allotted emergency duties, and musters and drills were to be carried out before and during each voyage.

Before the convention could be ratified, Europe was plunged into the horrors of the First World War. Of the 13 nations which took part in the conference, only five ratified the first convention: Great Britain, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, and Sweden.

The version shown here is the British ratification, signed by King George V on 30 December 1914. It bears his first great seal, showing the king in his uniform as Admiral of the Fleet, instead of the conventional image of the monarch on horseback.

The convention was revisited several times after the war, and new versions were established in 1929, 1948, 1960 and 1974. Since 1974 all changes have been made as amendments. These have arisen as a result of new technologies, such as better fire-retardant materials, as well as disasters such as the foundering of Costa Concordia, which resulted in new regulations regarding safety signage.

It is now administered by the International Marine Organisation, a branch of the United Nations. Signed by 168 countries, it represents 99% of the world’s shipping.