Record revealed

‘The Book of Negroes’: Black refugees who fought in the American Revolution

This volume offers a brief glimpse of the numerous ‘Black Loyalists’ who seized the American Revolutionary War as an opportunity to gain freedom from enslavement.

Important information

Please note this page highlights a document that discusses enslavement as a trade and as a condition, and that contains racist language. It is presented here to accurately represent our records and to help us understand the past.

Images

Image 1 of 4

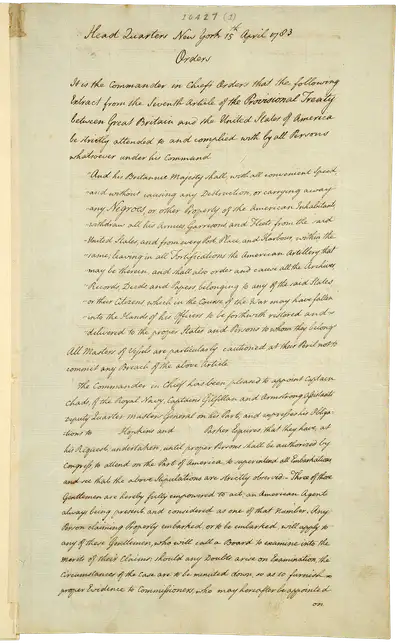

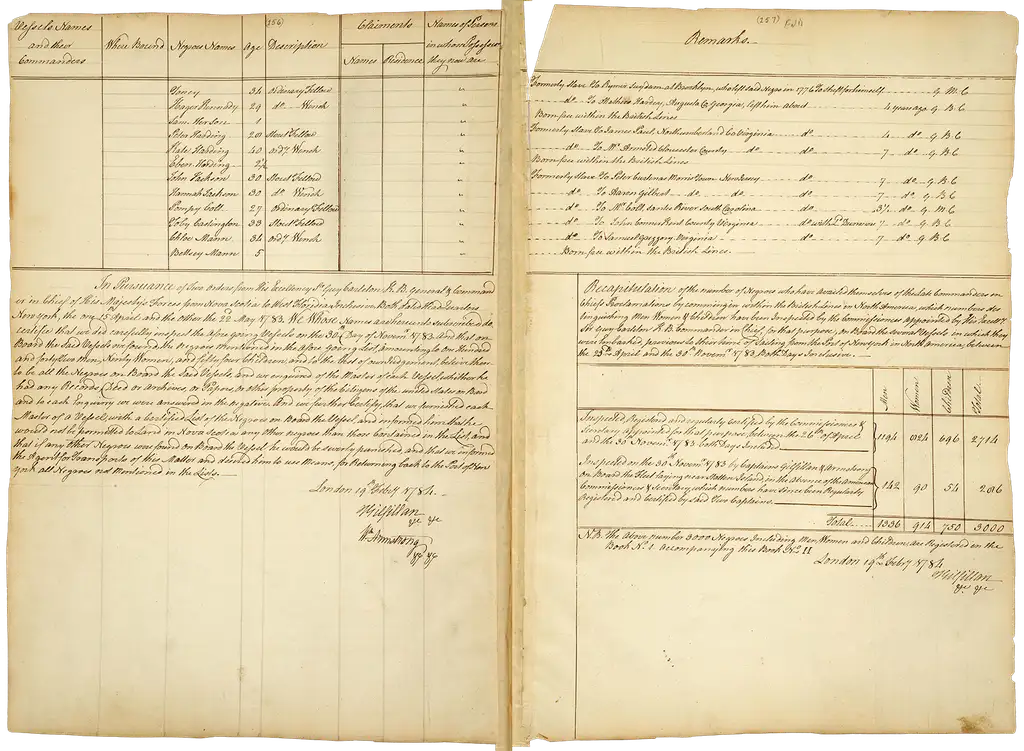

Double-page spread detailing Black Loyalists that embarked for Nova Scotia.

Partial transcript

[Sample rows from the table]

Vessels Names [and] their Commanders: Free Britain

Where bound: Port Rossway

Negroes Names: Leven Johnson

Age: 31

Description: Stout Fellow M

Claimants Names: [blank] Places of Residence: [blank]

Names of the Persons in whose Possession they now are: Sturg.s [Sturgess] Perry

Remarks: Formerly slave to Capt. Thomas Bell, Philadelphia left him at the Evacuation of said City. Gen.l [General] Birch's Certificate

[...]

Negroes Names: Jemima Bull

Age: 26

Description: Slender Wench B

Claimants Names: [blank] Places of Residence: [blank]

Names of the Persons in whose Possession they now are: Donald Ross

Remarks: Formerly slave to Mr. Bull Rhode Island left him with the British Troops in 1779 G.B.C

[...]

Negroes Names: Isaac Wilkins

Age: 15

Description: Stout boy

Claimants Names: Thomas Cropper, Places of Residence: Accomack. E. S. Virginia

Names of the Persons in whose Possession they now are: John Cowling

Remarks: Formerly slave to Jno [John] Wilkins Northampton Co.y [County] Virg.a [Virginia] left him 4 Years past. G.B.C.

Image 2 of 4

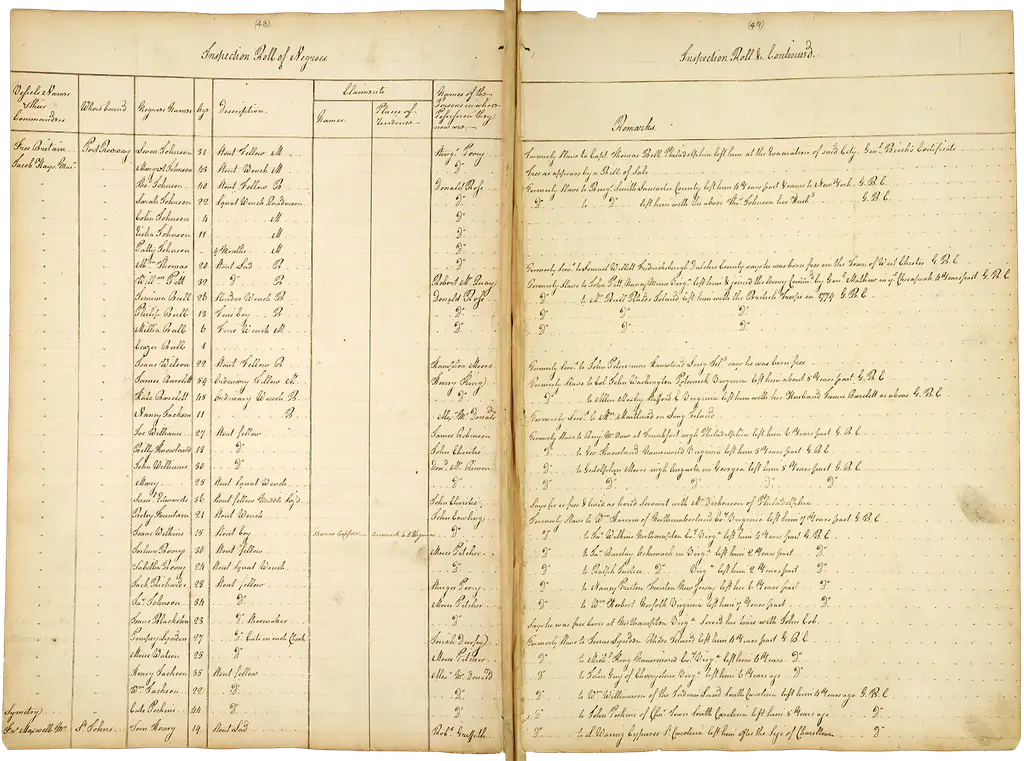

Page from the 'Book of Negroes' quoting from the 1783 treaty prohibiting the ‘carrying away of Negroes’.

Partial transcript

Head Quarters New York 15th April 1783

Orders

It is the Commander in Chief’s Orders that the following Extract from the Seventh Article of the Provisional Treaty between Great Britain and the United States of America be strictly attended to and complied with by all Persons whatsoever under his Command

“And his Britannic Majesty shall, with all convenient Speed,

“and without causing any Destruction, or carrying away

“any Negroes, or other Property of the American Inhabitants,

“withdraw all his Armies, Garrisons, and Fleet, from the said

“United States, and from every Port, Place, and Harbour, within the

“same, leaving in all Fortifications the American Artillery that

“may be therein, and shall also order and cause all the Archives,

“Records, Deeds, and Papers, belonging to any of the said States,

“or their Citizens, which in the Course of the War may have fallen

“into the Hands of his Officers to be forthwith restored and

“delivered to the proper States and Persons to whom they belong”

All Masters of Vessels are particularly cautioned, at their Peril, not to commit any Breach of the above Article

Image 3 of 4

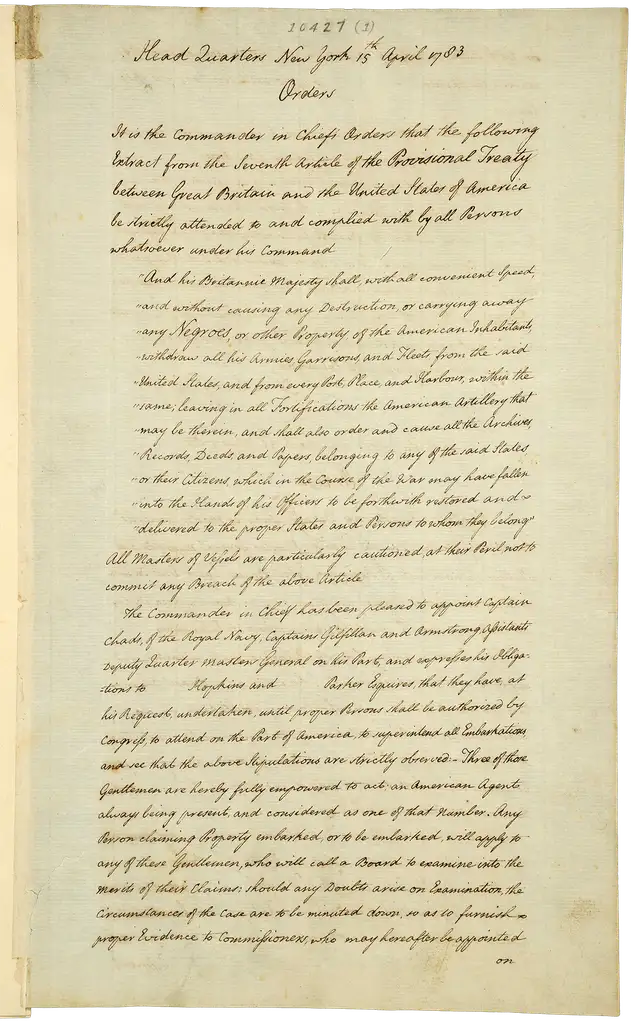

Minutes of hearings determining the re-enslavement of Black Loyalists.

Transcript

Friday July 24th 1783

Present

On the Part of

Great Britain.

Captain Armstrong

M.B. Phillips

Captain Cooke

America.

Lieut Colo. Smith

Case

Gerrard G Beekman claims two Negroe Children, one a Boy named Peter, the other a Girl named Elizabeth, lately embarked with their Father to go to Nova Scotia and brought on Shore for Examination

Evidence

The Claimant produces a Certificate from Pierre Van Cortland Esqr of the Manor of Cortland in the County of Westchester that in the year 1777 he gave the Wench (the mother of the said Children) with her Children to his Daughter Cornelia the Wife of the Claimant And upon Examination it appears that Samuel Doson (the Father of the Children) in April 1778 took them from the House of the said Pierre Van Cortland and brought them to the City of New York where they have remained ever since.

Opinion

The Board are of the Opinion that the Children ought to be delivered to the Claimant And he his hereby permitted to take and dispose of them as he may think proper.

August 2d 1783

Present

On the Part of

Great Britain.

Captain Armstrong

Major Phillips

Captain Cooke

America.

Lieut. Col. Smith

Case

Thomas Smith claims a Negroe Woman named Betty lately embarked to go to Nova Scotia and brought on Shore for Examination. She produces a Certificate from the Commandant Brigadier General Birch in the name of Elizabeth Truant That she was

Image 4 of 4

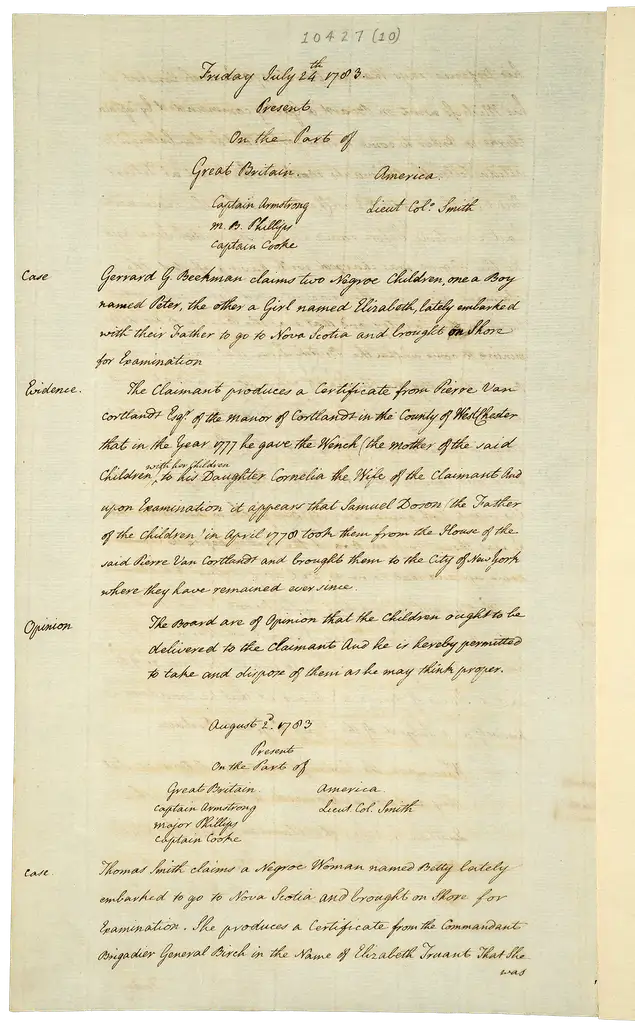

Final pages of the ‘Book of Negroes’, with the total number of embarked Black Loyalists listed as 3,000.

Partial transcript

In Pursuance of Two Orders from His Excellency Sr Guy Carleton K.B. General & Commander in Chief of His Majesty’s Forces from Nova Scotia to West Floridia Inclusive, Both dated Head Quarters New York, the one 15th April and the other the 22d May 1783. We Whose Names are hereunto subscribed do certifie that we did carefully inspect the afore going Vessels on the 30th Day of Novemr 1783. And that on board the said Vessels we found, the Negroes mentioned in the afore going List, amounting to One Hundred and forty Two Men, Ninety Women, and fifty four Children, and to the best of our Judgement, believe them to be all the Negroes on Board the said Vessels; and we enquired of the Master of each Vessel, whither he had any Records, Deed or Archives, or Papers, or other property of the Citizens of the united States on Board and to each Enquiry we were answered in the negative. And we further Certify, that we furnished each Master of a Vessel, with a Certified List of the Negroes on Board the Vessel, and informed him that he would not be permitted to Land in Nova Scotia any Other negroes than those Contained in the List, and that if any other Negroes were found on Board the Vessel he would be severely punished, and that we informed the Agent for Transports of this Matter and desired him to use Means, for Returning back to the Port of New York all Negroes not Mentioned in the Lists.

London 19th Febry 1784

[signed] Gilfillan &c &c

[signed] Wm. Armstrong &c &c

Why this record matters

- Date

- 15 April 1783 to 19 February 1784

- Catalogue reference

- PRO 30/55/100

This record captures a vital moment in the history of enslavement in the Atlantic world. It also offers a snapshot into the lives of thousands of formerly enslaved Black people, who strove to retain their freedom against immense odds.

When the American Revolutionary War broke out in 1775, enslaved people comprised approximately 20 per cent (500,000) of the colonies’ population. The British-American economy, particularly in the south, relied on the exploitation of their lives and labour.

In an effort to undermine the American rebellion and expand its own military forces, Britain offered freedom to any person, enslaved by a rebel American, who escaped and signed up to fight as a ‘Black Loyalist’. For the British, this was a practical advantage. For many enslaved people, it was a real opportunity for self-emancipation.

Thousands of Black men and women braved the dangers of war, and the risks of re-enslavement and punishment, to seize their own freedom. Black Loyalists served in a variety of roles during the war, including scouts, spies, engineers, and officers’ staff.

The peace treaty agreed between Britain, France, and the new United States of America in 1783 stipulated that all American property acquired during the conflict must be returned before the British forces departed. The Americans argued that this should include formerly enslaved people, and the treaty explicitly forbade the British from ‘carrying away any Negroes’.

The British were not necessarily against enslavement, but argued that they had offered a binding promise of freedom to Black Loyalists during the war. In compromise, freedom was offered to Black Loyalists who had self-emancipated prior to the ceasefire in 1782. Meanwhile, enslavers were permitted to bring evidence to a joint Anglo-American board to prove ‘ownership’ of Black Loyalists. Hearings included in this record provide examples of that process.

Those who successfully gained their freedom from American enslavers were entered into the ‘Book of Negroes’, and assigned to a ship departing New York. The Book names each man, woman, and child, along with a brief description and remarks; it also lists any ‘Claimants’ attempting their re-enslavement.

For many Black Loyalists, registration in the ‘Book of Negroes’ was a vital confirmation of their freedom from enslavement, recognised by both British and American signatories. Although their future remained uncertain, the emancipated Black Loyalist entries in this book represent a conclusive step in thousands of personal journeys of self-emancipation.

However, this record does not represent an abolitionist victory. While free Black Loyalists were offered land in the British colony of Nova Scotia, many people listed in the Book remained enslaved by British colonists also making that journey. Although they sailed alongside the free Black Loyalists, they would remain enslaved upon arrival in Nova Scotia. The fight for freedom was not yet over.

Related galleries

Featured articles

Record revealed

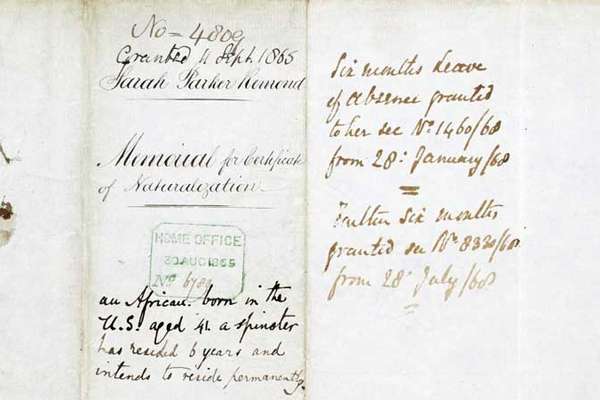

Sarah Parker Remond’s application to become a British Citizen

Sarah Parker Remond (1826–1894) fought for a more equal world as an abolitionist and suffrage supporter. Why and how did she apply for British citizenship?