Important information

This story contains descriptions of violence against children that some people may find upsetting

Prison licences

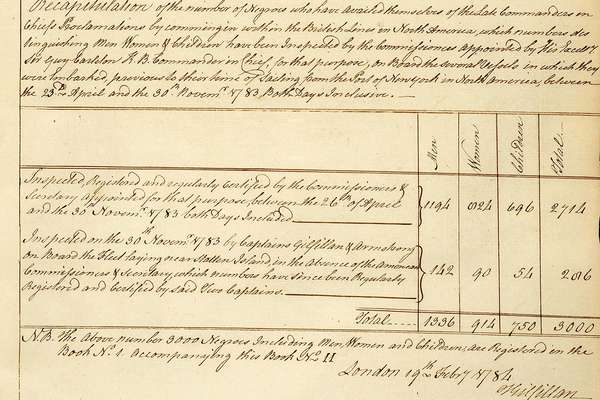

The National Archives holds approximately 5100 unique prison licence files for female prisoners for the years 1853 to 1887. Licences were issued to prisoners coming to the end of their sentence, giving them permission to leave early provided they did not re-offend, and a copy was added to their prison file.

These files can also include a photograph of the prisoner and background information on the woman and her crimes.

Taken as a whole, these files serve to highlight the lives of working class women, the difficulties they faced in their daily lives, and the range of crimes typically committed during this period.

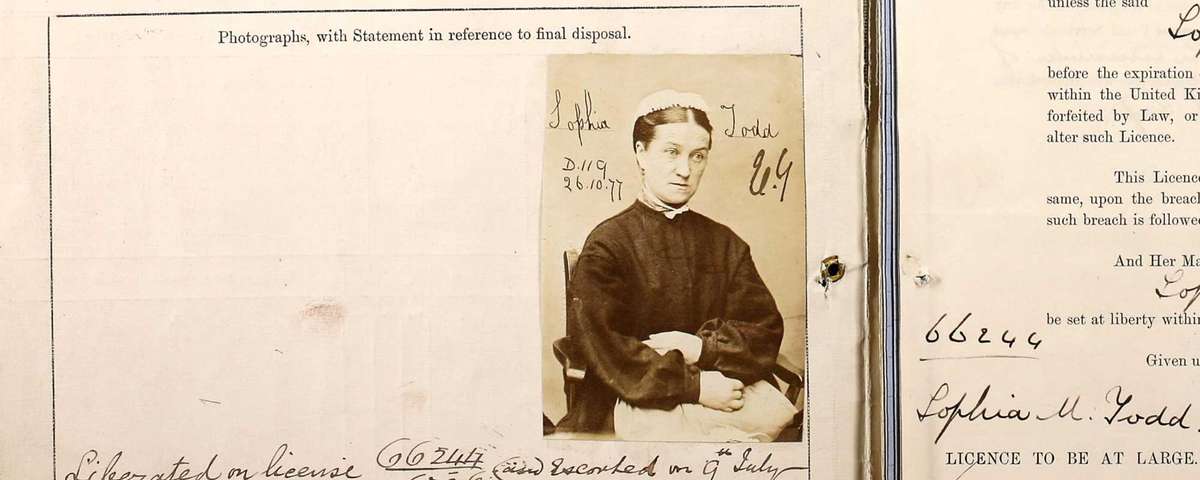

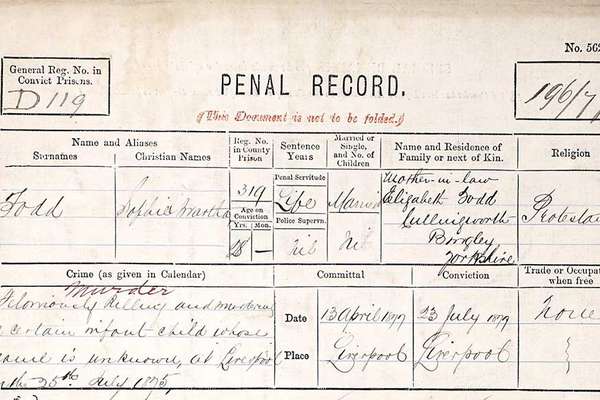

One such file concerns Sophia Todd who was sentenced at Liverpool Assizes in 1877 for the murder of a baby two years earlier.

A photograph of Sophia from her prison file. Catalogue reference: PCOM 4/51/18.

A knock at the door

Sophia’s prison file, together with the Home Office Supplementary file for the case tell the story which started on 25 July 1875. She was sitting in the kitchen of her rented accommodation with her landlady when there was a knock at the door. Sophia went to answer it and when she returned to the kitchen she was holding a baby.

Sophia maintained that she had been paid to look after the baby while the parents went to visit friends for the evening. The parents never returned, and the baby died in her arms that night. Sophia panicked and hid the baby in her trunk, wrapping the body in blankets.

Baby farming

Sophia did not fit the typical criminal stereotype. She was born in the West Indies to wealthy parents, she could speak several languages. She spent three years in Poland where she worked as a governess for the Reverend Boys-Smith, Chaplain to the Consul. She then moved to Russia where she worked for two more years before returning to England to take the position of governess for the children of Lord Decies.

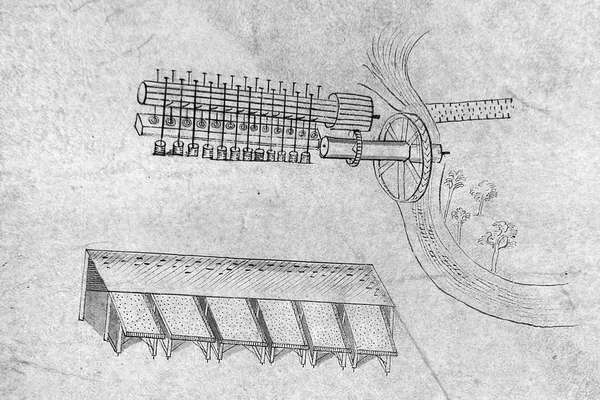

But could the events of that night in 1875 be seen another way? That Sophia was a 'baby farmer', making a living by taking money from vulnerable parents unable to look after their babies, murdering the children and disposing of their bodies.

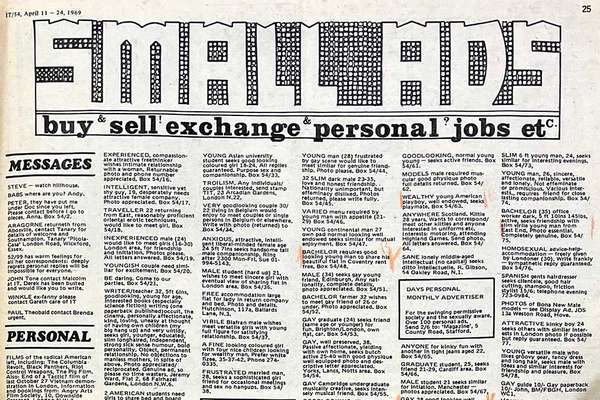

An illustration from 1870 of baby farmer Margaret Waters disposing of a child's body (Public domain via Wikimedia Common)

Soon after the baby died Sophia moved to another rented room, taking her trunk with her, before disappearing and leaving the trunk behind. It was left untouched until 9 March 1877 when the landlady, Mrs Oldham, opened and examined the contents. She found a bundle inside containing the body of a female child, which showed that the infant had been properly attended to after its birth. When a detective untied the bundle the head appeared to break from the body and dropped off.

Arrest

Sophia was apprehended near Manchester on 24 March 1877, and brought to Liverpool, where she made a statement to the detective to the following effect – that she had put an advertisement in the paper; and that, in consequence, the child was brought to her; that it died suddenly on the night it was brought, and that, being afraid, she had put it in her box and told her landlady that it had been called for.

When the body of the child was examined by medical men, and the clothes in which it was wrapped were submitted to microscopic examination, it was found that they were stained with blood and blood cells which showed that the blood must have flowed during life and not after death. No wound or injury was found on the remains.

Sentencing

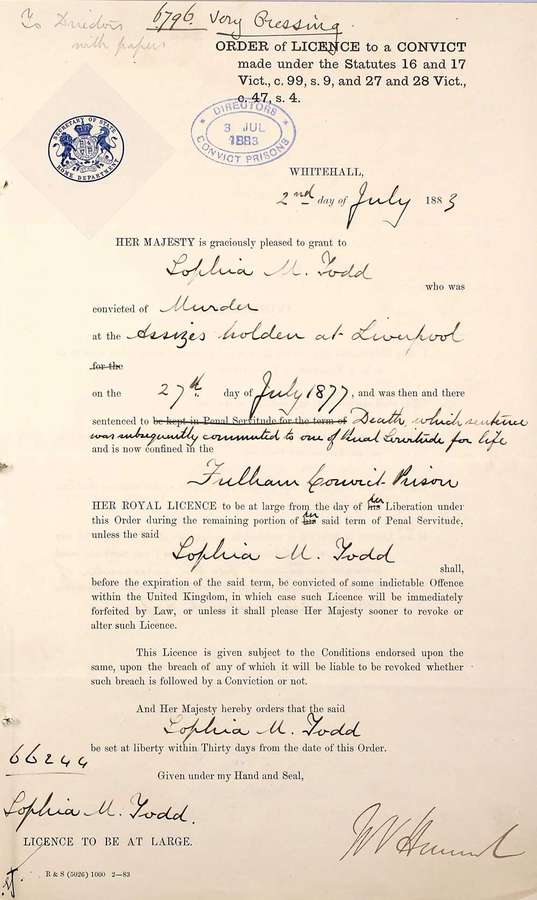

The jury in Sophia's trial returned a verdict of ‘Wilful Murder’ and a sentence of death was passed in the usual form. This was later commuted to a life sentence, following a campaign led by Sophia’s sister Sarah.

Sophia was eventually released on licence on 9 July 1883. This early release can perhaps be attributed to the decline in her health whilst in prison, so much so that her life was considered to be in danger.

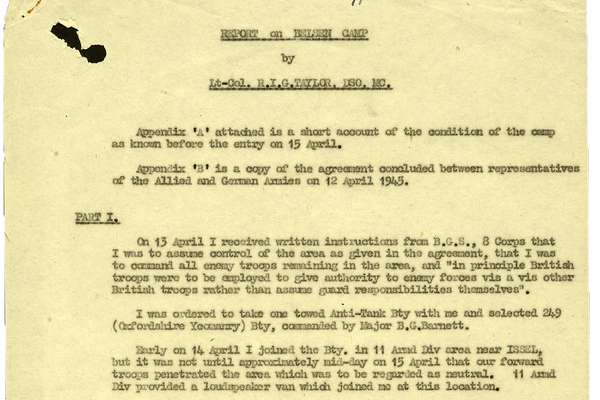

WHITEHALL

2nd day of July 1883

HER MAJESTY is graciously pleased to grant to Sophia M. Todd who was convicted of Murder at the Assizes holden at Liverpool on the 27th day of July 1877, and was then and there sentenced to Death which sentence was subsequently commuted to one of Penal Servitude for life and is now confined in the Fulham Convict Prison

HER ROYAL LICENCE to be at large from the day of her Liberation under this Order during the remaining portion of her said term of Penal Servitude unless the said Sophia M. Todd shall, before the expiration of the said term, be convicted of some indictable Offence within the United Kingdom, in which case such Licence will be immediately forfeited by Law, or unless it shall please Her Majesty sooner to revoke or alter such Licence.

This Licence is given subject to the Conditions endorsed upon the same, upon the breach of any of which it will be liable to be revoked whether such breach is followed by a Conviction or not.

And Her Majesty herby orders that the said Sophia M. Todd be set at liberty within Thirty days from the date of this Order.

Sophia's licence for her early release in 1883. Catalogue reference: PCOM 4/51/18.

Was Sophia Todd a baby farming murderer, or simply someone caught up in a series of ill-fated events? From the letters on her file we can see that her sister Sarah certainly believed she was innocent, and she knew Sophia better than anyone else.

Perhaps we shall never know the truth behind this case, one of the many thousands of true stories hidden in records series PCOM 4, the female prisoners’ licences.

Records featured in this article

-

- From our collection

- PCOM 4/51/18

- Title

- Sophia Todd's prison file

- Date

- 2 July 1883

-

- From our collection

- HO 144/27/66244

- Title

- Home Office Supplementary file on Sophia Todd

- Date

- July 1877

Read more

Blog: How to trace your criminal ancestors

The vast collections of criminal records are a rich source of detail for family historians and many others: they provide an insight not only into crime and punishment in the 1800s, but also into the daily lives of working people who are so often anonymous in the historical record.

Research Guide: Prisoners and prison staff

Records of prisoners and prison staff are held in a number of different places, including The National Archives, prisons themselves and local archives. This guide will help you find the records you need for your research

Research Guide: Prisons

A brief guide to finding records of prison administration and policy