Finding her passion

Sophia Jex-Blake was born in Hastings, England to a wealthy family. She was determined to make a difference, despite her family’s objections to her earning money. She was initially drawn to teaching, but after a trip to America was inspired to move into the field of medicine. Sophia saw the need for women to exist in the profession, in part to represent the specific medical needs of women.

At this time there were many barriers to women working in medicine especially as doctors, most notably the lack of education. The 1858 Medical Act established a register of qualified doctors, but the more formalised the profession became, the more explicitly women were excluded. Two women made it on to the register by 1865 by qualifying abroad, but such progress provoked more backlash.

Sophia published an essay in 1869 entitled Medicine as a Profession for Women. She argued women were not given the same access to education and qualifications as men, so had no opportunity to prove themselves.

We are told so often that nature and custom have alike decided against the admission of women to the Medical Profession, and that there is in such admission something repugnant to the right order of things, that when we see growing evidences of a different opinion… it surely becomes a duty… to test these statements by the above principles, and to see how far their truth is supported by evidence.

Sophia Jex-Blake, Medicine as a Profession for Women, 1869.

Sophia set out to prove her point. In 1869 she applied to study medicine at Edinburgh University.

The Edinburgh Seven

Sophia’s application was initially accepted, and then overruled. She rallied other students to challenge this, and a compromise was found – separate classes for female students. These women passed the entrance exams and were the first group of enrolled female undergraduate students at any British university. They were: Mary Anderson, Emily Bovell, Matilda Chaplin, Helen Evans, Sophia Jex-Blake, Edith Pechey, and Isabel Thorne. They became known as the Edinburgh Seven.

Although these women were a privileged minority, they nevertheless faced great challenges. Their smaller class sizes made courses more costly, male students were hostile, not all teachers were willing to support them and their access to practical study in the infirmary wards was restricted.

Photograph of Surgeon's Hall, Edinburgh, registered for copyright in 1903. Catalogue reference: COPY 1/460/307.

Things came to a head when the seven women were walking to Surgeons Hall for an examination and encountered a large group of demonstrators, including aggressive male students. The incident became known as the Surgeons Hall Riot and gained significant publicity and public sympathy.

During Sophia’s medical student days, she was close to Ursula Du Pre and they are believed to have been lovers. In 1871 they were listed as living together, and remained close throughout their lives.

Despite the Edinburgh Seven’s tenacity, the university still denied the women the rightful qualifications for the studies they had undertaken. The matter went to various court levels, but the ultimate outcome was the same. Trying to progress within the existing system was not working, so Sophia tried a different approach.

Medical schools

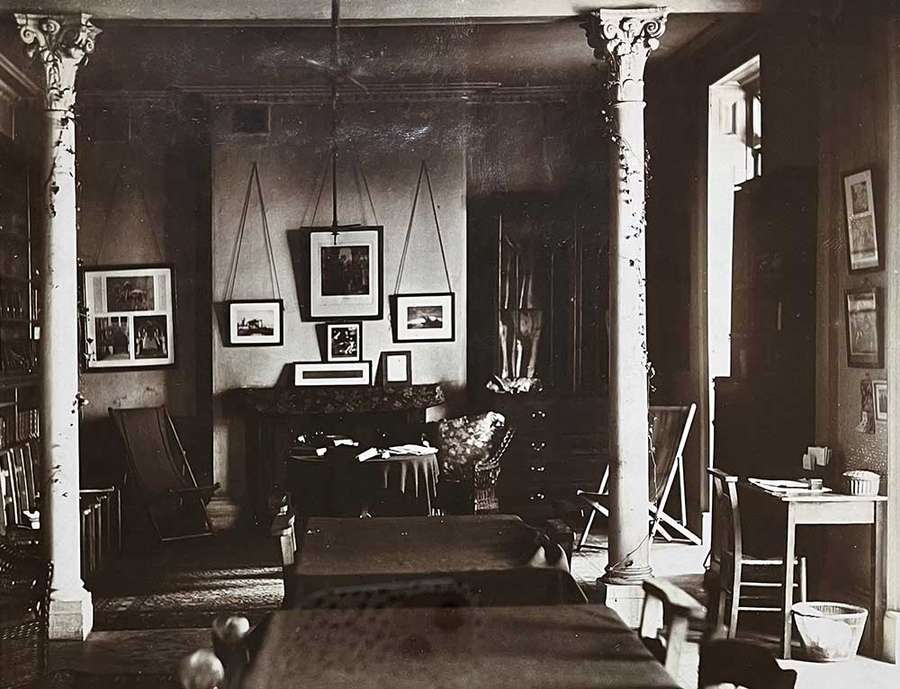

Sophia, and other pioneering women, founded the London School of Medicine for Women in 1874, while she was still a student herself. The school initially had 14 female students.

Photograph of the common room of the London School of Medicine for Women at 30 Handel St, Brunswick Square. Registered for copyright in 1900. Catalogue reference: COPY 1/447/603.

The General Medical Council was reticent to engage in the debate around women and medicine, however it did send a statement to the Privy Council in 1875.

The medical council are of opinion that, the study and practice of Medicine and Surgery, instead of affording a field of exertion well fitted for Women, do, on the contrary, present, special difficulties which cannot be safely disregarded; but the Council are not prepared to say that Women ought to be excluded from the Profession

Catalogue reference: PC 8/206

The debate was shifting. The following year a private members bill was passed to allow (but not enforce) the acceptance of women candidates by exam boards. In 1877, Sophia qualified as a doctor after taking her medical examinations in Switzerland, away from the spotlight in England.

Sophia was headstrong and not everyone agreed with her. After a dispute with the London School, she returned to Scotland to start her own medical practice and ended up forming the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women in 1886.

At this time Sophia met Margaret Todd, one of the first students at the Edinburgh School. They lodged together close to the premises and had a very close relationship for several decades. Records indicate they may have been romantic partners.

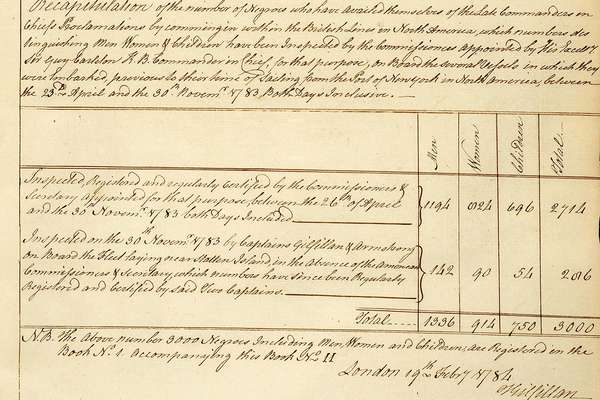

Scholarships for Indian women

The logistics of running a medical school were challenging, Sophia appealed to her contacts to help fund the institution. She was particularly keen to encourage overseas students to be trained.

Mr James Cropper offered to financially support the medical education of Indian women. While training was available to women in India, similar struggles to those in the UK persisted and formal qualifications were not yet available. A number of Indian women were supported by the Cropper scholarship to study at the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women and implement their training in India, including Lydia Datt and Rose Govindurajulu.

In 1897 the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women closed, having educated 80 women, 53 of whom made it on to the British Medical Register. The scholarship fund was to be reallocated. Surviving correspondence shows the selection of Queen Margaret College in Glasgow as an alternative scholarship school.

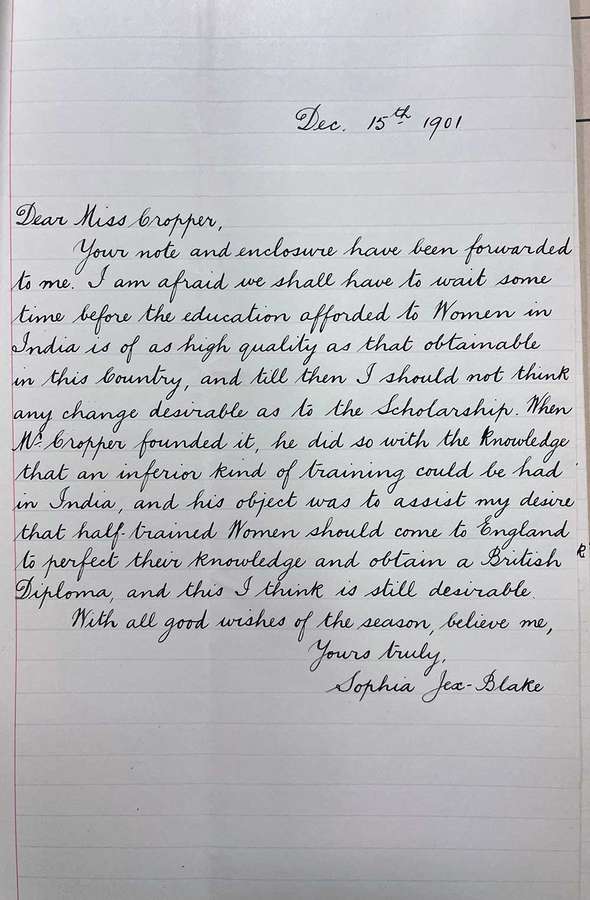

Letters between Sophia and Mary Cropper, daughter of James Cropper, show their continued interest in this fund and highlight some of the individuals who received support to study at Queen Margaret College.

Mary Cropper was increasingly keen to see the scholarship handed to a hospital in India, ‘I am feeling strongly but now that there are facilities for Indian women to study medicine in India my father scholarship or to be transferred there’.

This funding certainly helped Indian women but also represented entrenched colonial attitudes.

Dec. 15th 1901

Dear Miss Cropper,

Your note and enclosure have been forwarded to me. I am afraid we shall have to wait some time before the education afforded to Women in India is of as high quality as that obtainable in this country, and till then I should not think any change desirable as to the Scholarship. When Mr Cropper founded it, he did so with the knowledge that an inferior kind of training could be had in India, and his object was to assist my desire that half-trained Women should come to England to perfect their knowledge and obtain a British Diploma, and this I think is still desirable.

With all good wishes of the season, believe me,

Yours truly,

Sophia Jex-Blake

Letter from Sophia Jex-Blake to Mary Cropper from 1901 discussing education of Indian women. Catalogue reference: TS 18/98.

Return to Sussex and life with Margaret

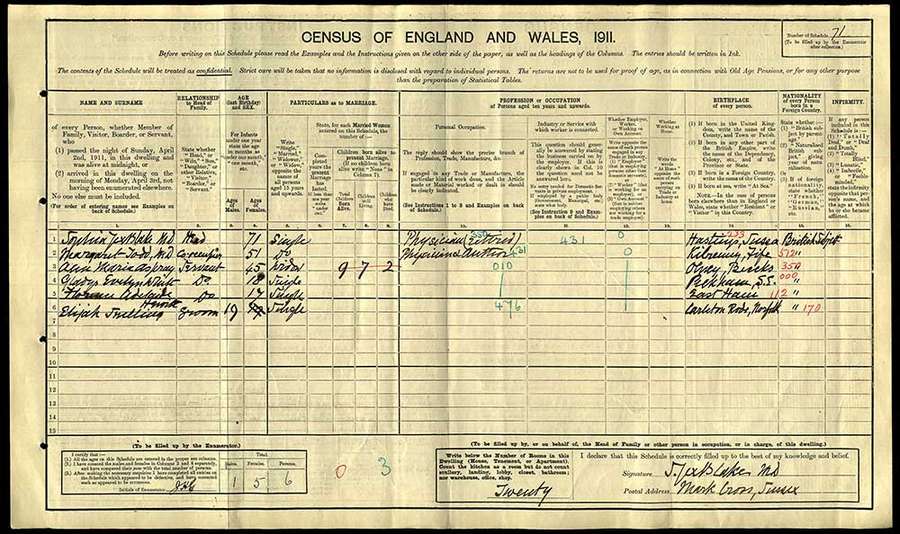

For much of her later life, Sophia lived with Margaret Todd. After the school closed, they moved to Sussex, and are listed as living together on both the 1901 and 1911 censuses.

Photograph of Margaret Todd taken around 1916. © National Portrait Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

By 1911, Margaret is listed as a ‘co-occupier’ of their East Sussex home. Both had MD noted after their names in the census, in acknowledgement of their hard fought for medical qualifications. Margaret was also an author, successfully writing fiction that included reflections on being a woman in the medical profession.

The 1911 census record for Dr Sophia Jex-Blake, Dr Margaret Todd and their servants in Wadhurst, Sussex. Catalogue reference: RG 14/4916.

Sophia died in 1912, having made a huge impact on the lives of many women, those in the medical profession and those who received care from them.

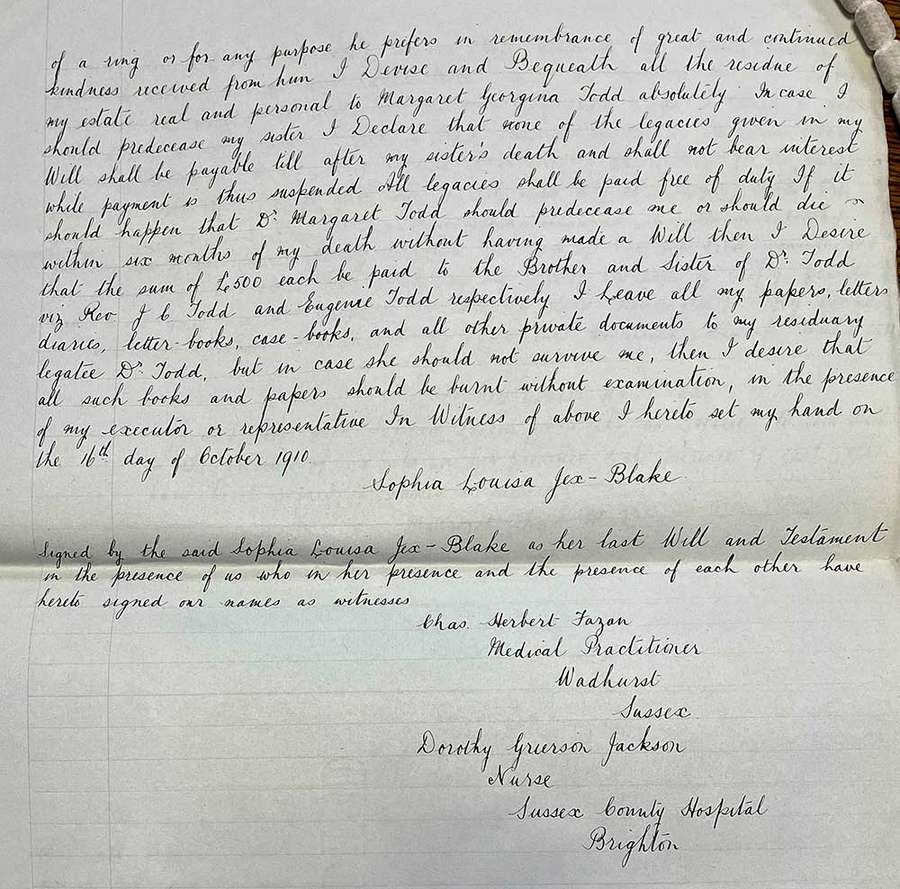

Last will and testament

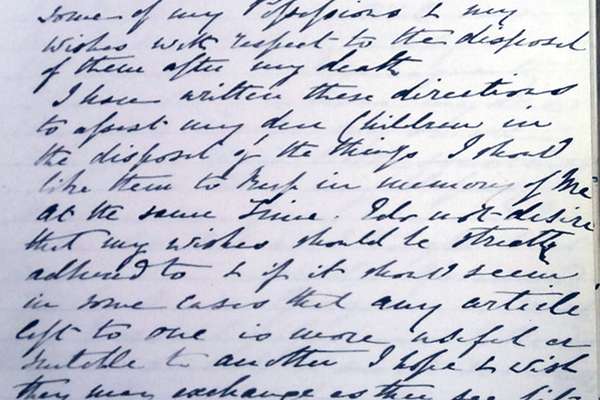

The National Archives do not usually hold wills from this period, but the complications around administering the scholarship fund meant a copy of Sophia’s will was consulted upon her death and was preserved in a Treasury Solicitors file. Margaret and Ursula du Pre both became administrators of the fund.

The will provides a unique window into what was important to Sophia throughout her life. Sophia was wealthy and left money to various notable causes and individuals, including the Society for Women’s Suffrage, the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women and a number of her female friends who were qualified doctors.

Margaret was one of two executors for the will and received the remainder of her estate ‘real and personal’. The nature of Sophia and Margaret’s relationship is implied in the text of the will itself.

Sophia stipulated:

I leave my papers, letters, diaries, letter books, case books and all other private documents to my residuary legatee, Dr Todd, but in case she should not survive me, then I desire that all such books and papers should be burnt without examination in the presence of my executor or witness.

Will of Sophia Jex-Blake. Catalogue reference: TS 18/98

I Devise and Bequeath all the residue of my estate real and personal to Margaret Georgina Todd absolutely. In case I should predecease my sister I Declare that none of the legacies given in my will shall be payable till after my sister’s death and shall not bear interest while payment is thus suspended. All legacies shall be paid free of duty. If it should happen that Dr Margaret Todd should predecease me or should die within six months of my death without having made a Will then I Desire that the sum of £500 each be paid to the Brother and Sister of Dr Todd viz Rev J C Todd and Eugenie Todd respectively. I leave all of my papers, letters, diaries, letter-books case-books, and all other private documents to my residuary legatee Dr Todd, but in case she should not survive me, then I desire that all such books and papers should be burnt without examination, in the presence of my executor or representative In Witness of above I hereto set my hand on the 16th day of October 1910

Sophia Louisa Jex-Blake

The second page of a copy of the will and codicils of Sophia Louisa Jex-Blake MD. Catalogue reference: TS 18/98.

LGBTQ+ history can be obscured by a lack of surviving records because it often did not feel safe or acceptable to preserve such items. Margaret was clearly Sophia’s most trusted companion. These archival records can tell us a little about the pair’s relationship and the important work Sophia did throughout her life to promote women’s equality, in medicine and beyond.

Margaret died a few years after Sophia in 1918. Continuing in their tradition, she also left money to the advancement of women in medicine.

Margaret’s last legacy was a biography of Sophia, published just before her death. The pair are buried together in St Denys' Churchyard, Rotherfield, Sussex, near to where they lived.

Records featured in this article

-

- From our collection

- COPY 1/460/307

- Title

- Photograph of Surgeon's Hall, Edinburgh

- Date

- 1903

-

- From our collection

- COPY 1/447/603

- Title

- Photograph of the common room of the London School of Medicine for Women

- Date

- 1900

-

- From our collection

- PC 8/206

- Title

- Statement from the General Medical Council regarding women in medicine

- Date

- 1875

-

- From our collection

- TS 18/98

- Title

- Documents from the Treasury Solicitor regarding the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women

- Date

- 1893-1913

-

- From our collection

- RG 14/4916

- Title

- Census record for Sophia Jex-Blake and Margaret Todd

- Date

- 1911

Read more

Research Guide: Sexuality and gender identity history

This guide will help you find records relating to sexuality, including gay, lesbian and bisexual histories, as well as transgender and gender identity history.