Early life

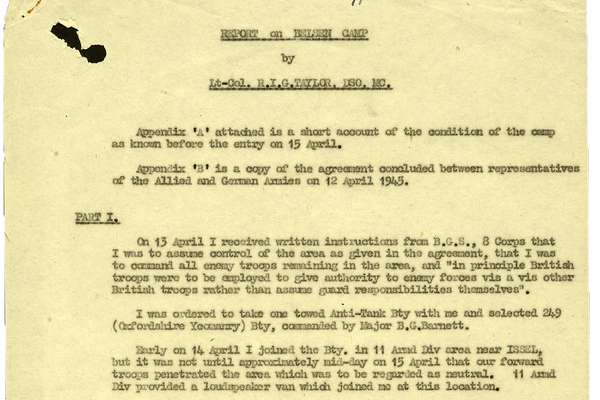

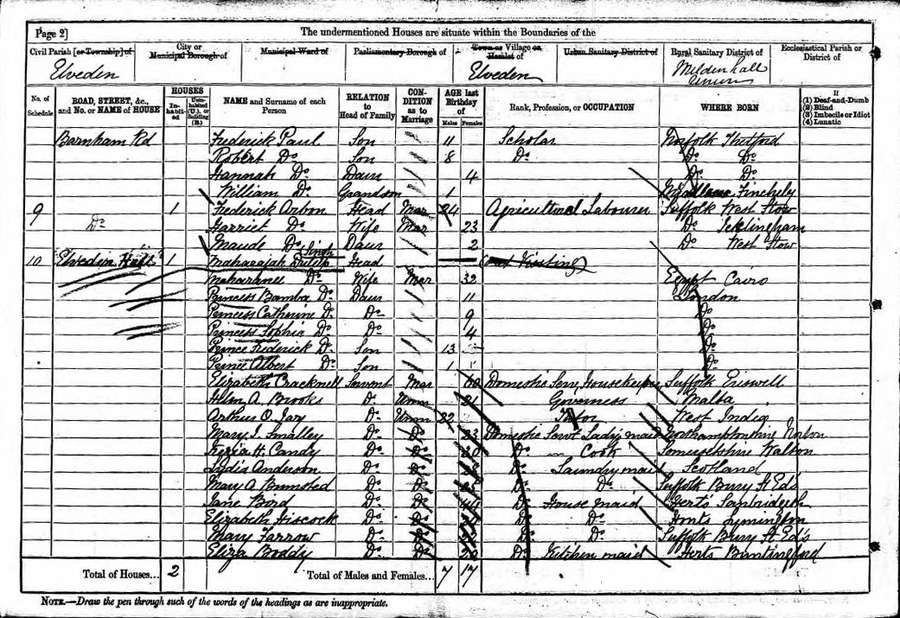

Sophia, born in 1876 in London, was the daughter of Maharaja Duleep Singh, the last Maharaja of the Sikh Empire, and Bamba Müller, of German and Ethiopian descent. Our records first mention Sophia at just four years old, living with her family in their grand home at Elveden Hall, Suffolk. At that time, the five siblings – Victor, Frederick, Bamba, Catherine (later joined by Albert) – lived with their parents and 19 domestic staff, including ladies’ maids and valets.

Maharaja Duleep Singh had a complex relationship with the British monarchy. At the age of 11, his Sikh Empire was taken from him by the British, and he was exiled from India. Despite this, he had a close friendship with Queen Victoria when they were young. Throughout the family’s time in England, they were kept under surveillance by the India Office.

Sophia’s parents' relationship broke down, and in 1887 Bamba Müller sadly died. Maharaja Duleep Singh spent the last six years of his life in Paris, campaigning to be restored to the throne of Lahore and died in 1893. The children were put under the guardianship of Arthur Craigie Oliphant and Sophia was sent to a small girls’ school in Brighton.

1881 census form, showing the Duleep-Singh family at Elveden Hall, Suffolk. Catalogue reference: RG 11/1846

Life at Hampton Court

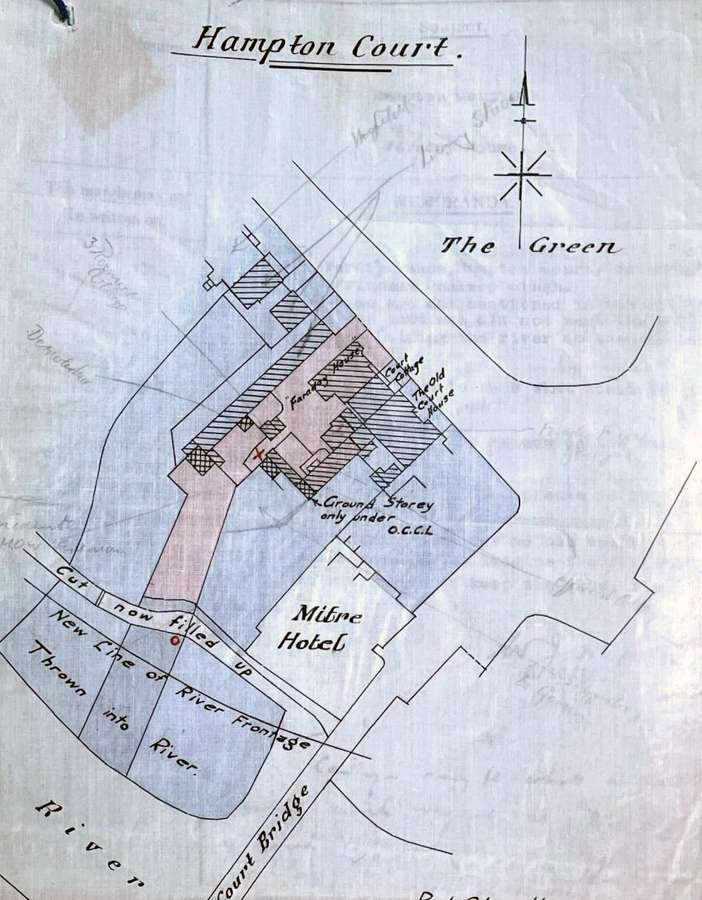

Sophia was the goddaughter of Queen Victoria, who provided for the sisters after the death of their parents. In 1897, a warrant placed Bamba, Sophia and Catherine in possession of Faraday House, on the Hampton Court Estate. The Queen also granted her an allowance of £200 a year to maintain it.

The sisters were moving into a home at the heart of the British establishment; some of the neighbouring tenants on the grounds had helped suppress the ‘Indian Mutiny’, which had brutally kept British rule in India. As one of the younger children, Sophia was more protected from the experiences of empire than her siblings, who held a deep distrust of the British.

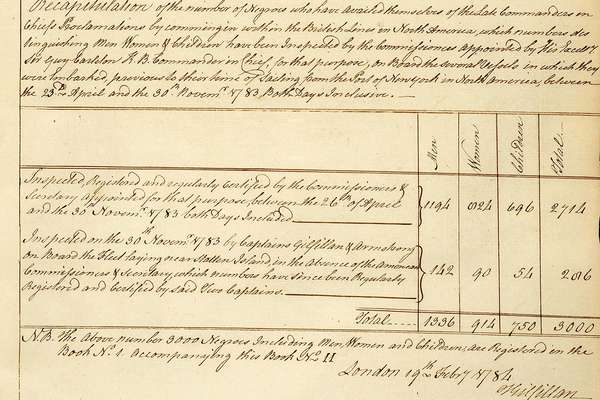

Map of Faraday House, surrounding cottages and land. Catalogue reference: WORK 19/315

Life at Faraday House was not what they had been used to at Elveden Hall – they had to seek approval for any changes in the property. Office of Works files show tensions between the Duleep Singh family and the authorities, as they requested modern conveniences like electric lights, hot water and separate bathrooms. Sophia loved her garden and took an interest in the trees and plants, often objecting to works that might harm them. Her love for music and animals was evident in their home.

While Catherine was still involved in Faraday House, she had fallen deeply in love with her German governess, Lina Schäfer, and the couple made a life together in Germany. While Bamba moved to Lahore and married Dr David Sutherland.

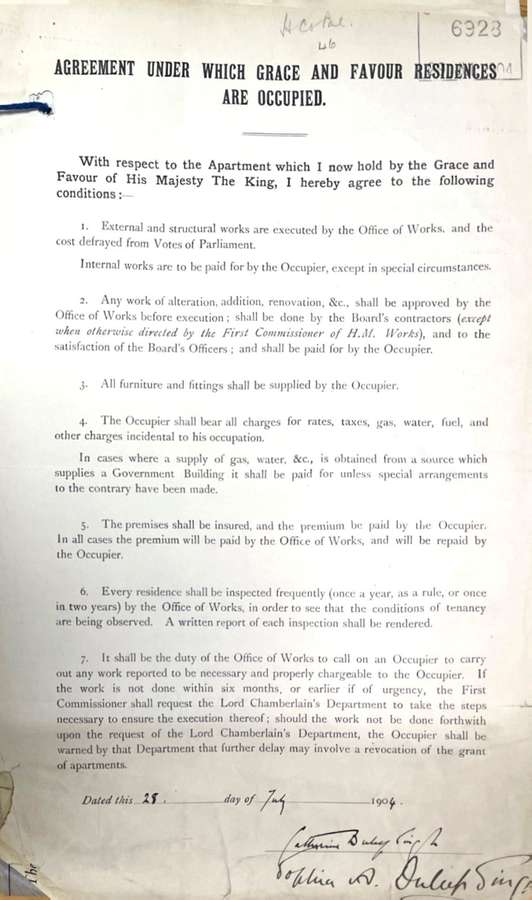

AGREEMENT UNDER WHICH GRACE AND FAVOUR RESIDENCES ARE OCCUPIED.

… I hereby agree to the following conditions:

- External and structural works are executed by the Office of Works, and the cost defrayed from Votes of Parliament.

Internal works are to be paid for by the Occupier, except in special circumstances - Any work of alteration, addition, renovation, &c., shall be approved by the Office of Works before execution; shall be done by the Board’s contractors (expect when otherwise directed by the First Commissioner of H.M. Works), and to the satisfaction of the Board’s Officers; and shall be paid for by the Occupier

- All furniture and fittings shall be supplied by the Occupier

- The Occupier shall bear all charges for rates, taxes, gas, water, fuel, and other charges incidental to his occupation…

- The premises shall be insured, and the premium be paid by the Occupier. In all cases the premium will be paid by the Office of Works, and will be repaid by the Occupier.

- Every residence shall be inspected frequently (once a year, as a rule, or once in two years) by the Office of Works, in order to see that the condition of tenancy are being observed…

- It shall be the duty of the Office of Works to call on an Occupier to carry out any work reported to be necessary and properly chargeable to the Occupier…

Dated this 28 day of July 1904

[signed]

Catherine Duleep Singh

Sophia Duleep Sing

Agreement under which grace and favour residences are occupied, signed by Sophia and Catherine, 1904. Catalogue reference: WORK 19/315

Travels to India

The Duleep Singh siblings took various voyages to India, as can be seen across passenger lists from the 1890s onwards. This was done cautiously, given the exile of their father.

A visit by Sophia in 1907 proved an awakening for her. On this trip she encountered extreme poverty and the reality of British rule in India, listening to nationalist speakers like Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Lala Lajpat Rai. She was also confronted with the scale of what her father had lost. Her more critical perception of the British led her to also question things on her return, where she was surrounded by the growing women’s suffrage movement.

Votes for women

Sophia was described as a new woman, embracing smoking and cycling, while also being deeply committed to women's rights. The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) had been founded in 1903, determined to use any means necessary to win the vote, heralding a new era of the suffrage movement – Sophia signed herself up.

Like many suffrage supporters, Sophia was part of multiple societies, attempting to use a variety of methods to gain women the vote. She was also a member of the Women’s Tax Resistance League, who argued taxation without representation was tyranny. Sophia was tried at local courts on several occasions for not paying taxes. Alternatively, Catherine supported the non-militant National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies.

The movement was dominated by white women and the focus was on British women’s right to vote. Suffrage organisations could be very traditional, parades often celebrated the Empire – such as the 1911 Empire Pageant – which had a delegation representing India. Sophia and Catherine are some of the few known women of colour to be involved – it is on the basis of their elevated status that we know their names and stories today.

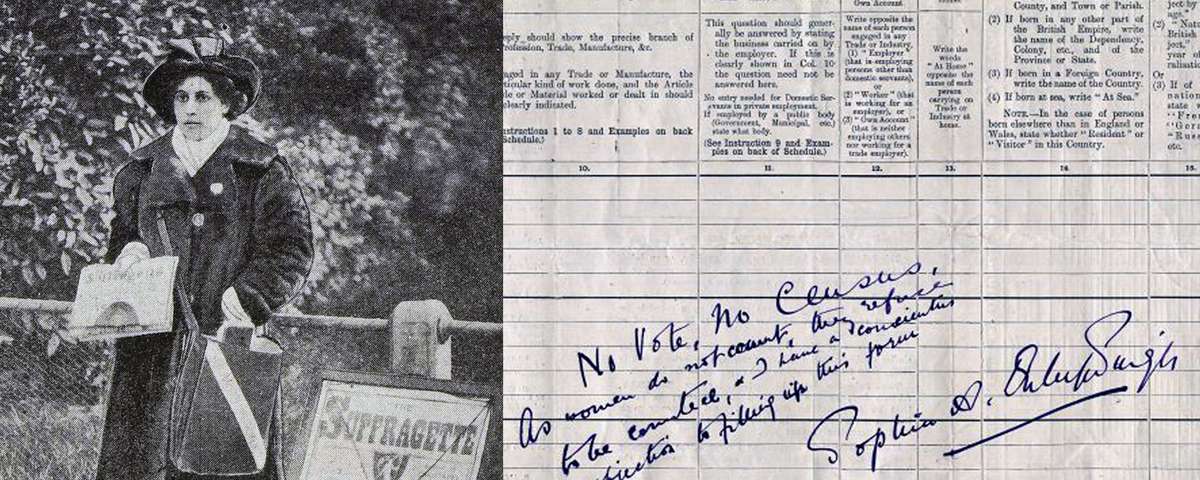

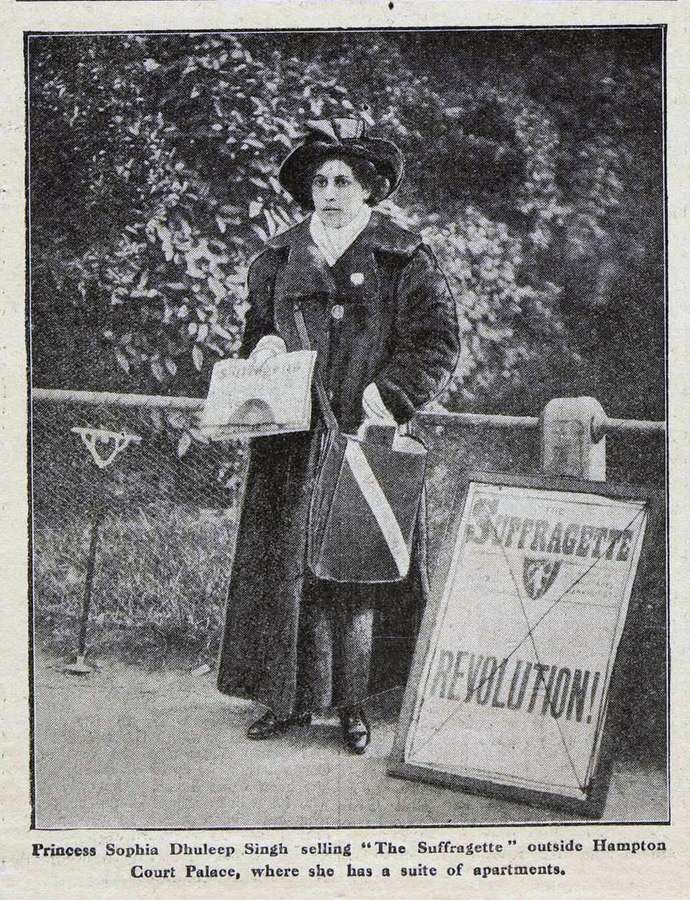

Sophia selling copies of The Suffragette outside her home in Hampton Court Palace grounds, April 1913. Image from a copy of The Suffragette seized in a raid of the printers. Catalogue reference: ASSI 52/212/17

Black Friday

18 November 1910 saw a turning point for the suffrage movement, on a day known as Black Friday. Frustrated at repeated disappointments, dozens of women marched on Parliament, with Sophia in the first deputation. Protestors refused to disburse, leading to hours of brutal clashes between the police and suffragettes. A later report to the Home Office described the physical, verbal and sexual assaults these women faced at the hands of the police.

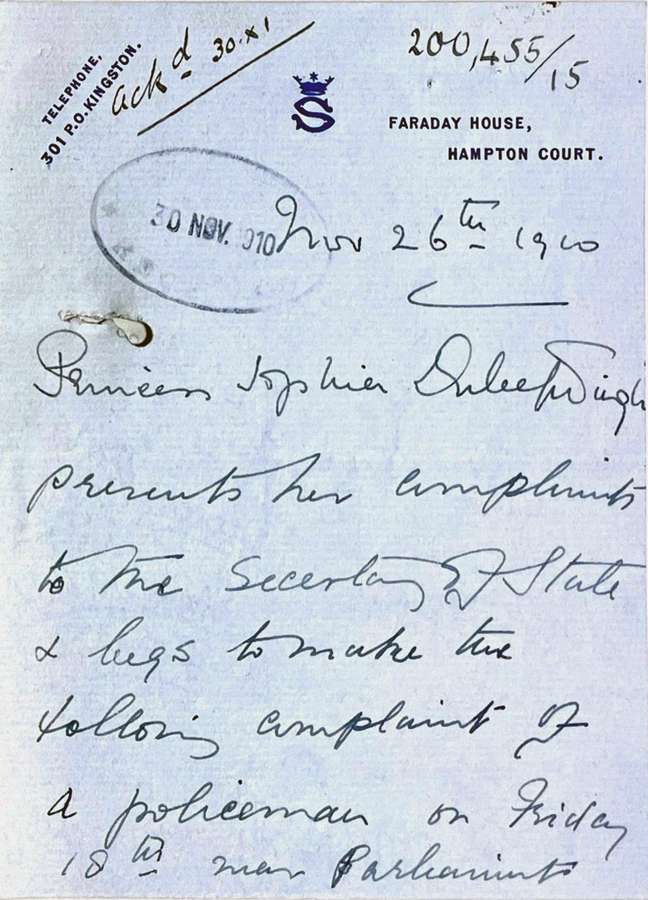

200,455/15

FARADAY HOUSE, HAMTON COURT.

Nov 26th 1910

Princess Sophia Duleep Singh presents her compliments to the Secretary of State and begs to make the following complaint of a policeman on Friday 18th Nov Parliament Square. His number is V.700. He pushed a poor exhausted lady so that she fell onto her hands & knees & when she got up, he took hold of her most roughly and pushed her along. Princess Sophia followed some distance to see what happened, the lady (whose name she is not aware of) was eventually released. The policeman was unnecessarily and brutally rough and Princess Sophia hopes he will be suitably punished.

Page one (of four) of a letter of complaint from Sophia to the police after the Black Friday protests. Sent from Faraday House. Catalogue reference: HO 144/1106/200455

Sophia was in the fray and witnessed the violence. She noted down the number of one police officer, after observing them push a 'poor exhausted lady so that she fell onto her hands and knees'. Sophia argued it was 'unnecessary and brutally rough'. Police responded to these accusations by arguing, 'the ladies themselves resorted to physical force and no doubt to meet it physical force had to be used', seeing these complaints as 'part of a plan to discredit the Police who tried to do their duty under most difficult conditions.' A curt note from Home Secretary Winston Churchill read, 'Send no further reply to her' (catalogue reference: HO 144/1106/200455).

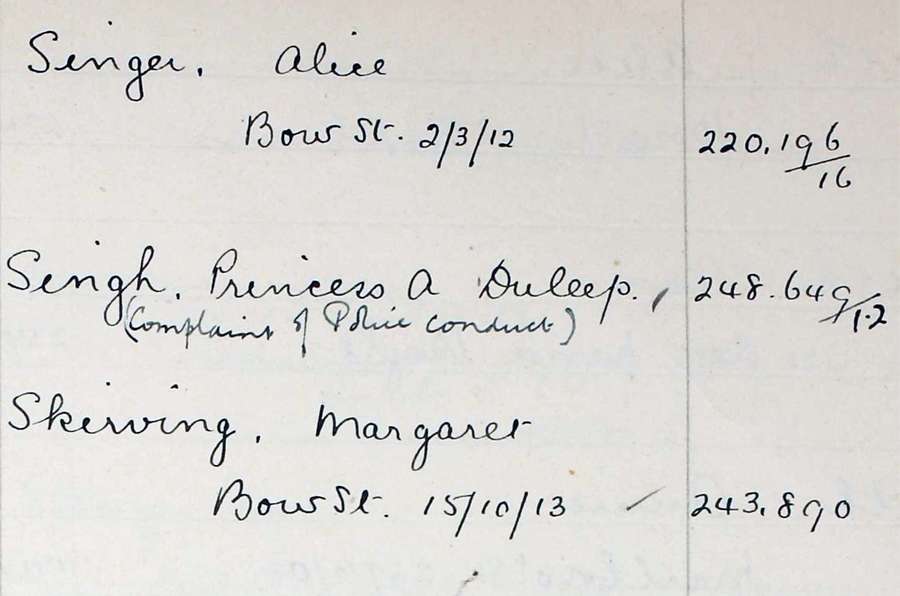

It is notable that Sophia was treated differently to other suffragettes, on this occasion and others. She was aware of the press attention her status attracted and so were the police – they were keen to avoid any extra publicity or controversy. Though she gets a mention on the index of suffragettes arrested, compiled by the Home Office, her entry only relates to her complaint about Black Friday.

Section of the suffragette index of arrests, listing 'Sing, Princess a Duleep (complaint of police conduct)'. Catalogue reference: HO 45/24665

Protests continue

As a suffragette, Sophia regularly participated in meetings and sold suffrage literature, activities that were core to the movement. She used her privileged position to make a stand, selling copies of The Suffragette newspaper on the grounds of Hampton Court and encouraging others in the Kingston branch to also sell the paper.

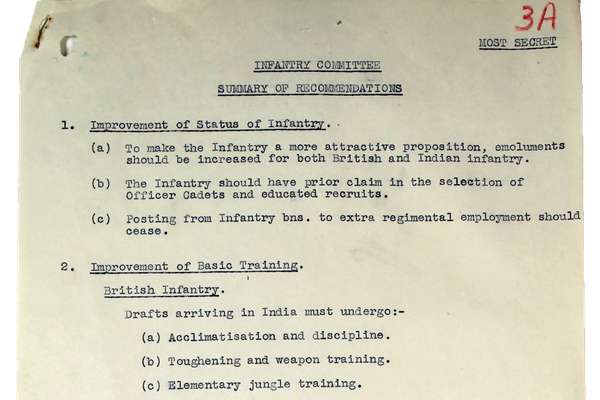

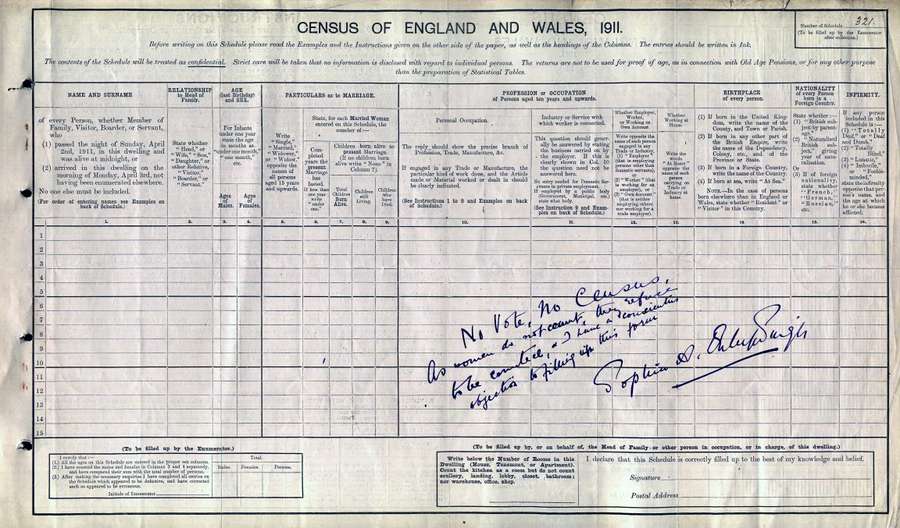

In 1911, the Women's Freedom League organised a mass census boycott, a nonviolent direct action to make the government pay attention to their cause. Many women evaded the census arguing that if they were to not be treated as citizens with a democratic voice, why should they be counted. But Sophia was determined to leave her mark. From her establishment home at Hampton Court, she wrote in vivid blue ink across her census schedule:

No Vote, no census, as women do not count, they refuse to be counted, I have a conscientious objection to filling in this form.

She added her name in large, bold letters. The following census sheet contains brief information on Sophia, compiled by the enumerator, estimating her age and wrongly assuming she had been born in India.

Protest written by Sophia on her census enumeration form at Faraday House, Hampton Court, 1911. Catalogue reference: RG 14/3561

In 1912, Hurst Park was attacked by suffragette arsonists – this was just across the river from Hampton Court. Government records show the palace – along with many other public buildings – was identified as at risk of attack; more security was authorised, fire extinguishers obtained, and its public galleries closed. Sophia, as an open and active suffragette living on these grounds, was an increasing challenge to the government and removing her from Faraday House was considered. But the heightened atmosphere of the movement was about to change.

The First World War and beyond

In July 1914, the First World War started, and the WSPU immediately turned to support the war effort, halting militant activities. Sophia was one of the women who took part in the Women’s Right to Serve March, aiming to bolster recruits and get fair treatment for women.

Sophia volunteered as a nurse with the Voluntary Aid Detachment in Isleworth, not far from Hampton Court. The Red Cross hold her VAD medal card, showing she was signed up to seven shifts a week. In 1917, she 'left to take up work for India', trying to raise morale among Indian soldiers. Here she visited them in hospital and as the honorary secretary to the India Day fund, which was designed to raise money to provide for Indian troops.

In 1918, Sophia signed an address calling for votes for Indian women, and in 1919 she was part of a deputation to the India Office who 'sought the franchise as their Western sisters sought it in the pre-war days'.

Some women in Britain were granted the vote in 1918, and Equal Francise was given in 1928. The journey for Indian women’s right to vote took longer in incremental steps, with some provincial rights granted from 1921.

A place of refuge

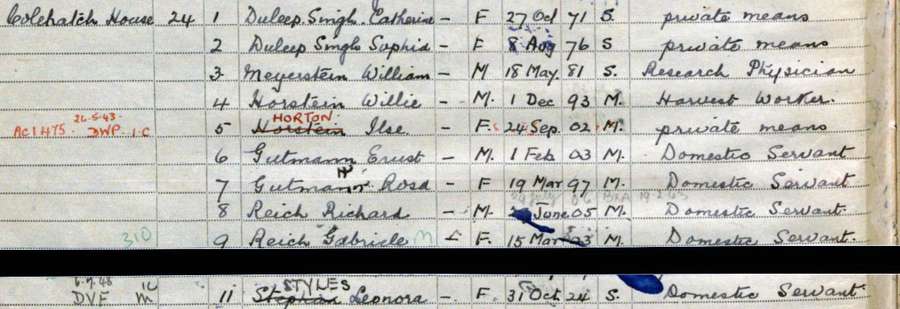

The Second World War prompted Sophia and Catherine to relocate to houses at Coalhatch House, in Penn, Buckinghamshire. The rise of the Nazis and the sad death of Catherine’s long-term partner, Lina, induced her to move back from Germany, and the increasing risk of being in wartime London pushed Sophia out of the city.

The sisters lived opposite each other and created a home for people seeking sanctuary. Sophia took in evacuees siblings John (11), Shirley (9) and Michael (7) Sarbutt from West London. The Sarbutt children later described the anticipation of meeting the princess and how she cared for them.

Catherine was said to have helped at least a dozen Jewish German people escape Nazi persecution, providing them refuge in her home, including Wilhelm and Ilse Hornstein, Ernest and Rosa Gutmann, and Richard and Gabriele Reich. The 1939 Register offers a window into these busy households. Most of these couples were interned not long after this as recorded on our Aliens Department internee’s index. They were able to list employment with Princess Duleep Singh and all were eventually deemed exempt from internment under various criteria and were released by December 1940.

List of residents at Colehatch House and Rathenrea bungalow on Hammersley Lane, Penn, Buckinghamshire, on the 1939 Register. Catalogue reference: RG 101/2162C

Later years and legacy

Sophia and Catherine continued to live in Penn for the rest of their lives.

Women’s rights remained important to Sophia, and in the 1940s she acted as the Honorary Treasurer for ‘Mrs Pankhurst’s statue plant fund appeal’, ensuring this monument was looked after and respected. She subscribed to the Suffragette Fellowship for the rest of her life, continuing to fight for their aims:

To perpetuate the memory of the pioneers and outstanding events connected with women’s emancipation and especially with the militant suffrage campaign 1905–1914.

To secure women's political, civil, economic, educational and social status on the basis of the equality of the sexes, and co-operate from time to time with other organisations working to the same end.

The Suffragette Fellowship

Sophia died on 22 August 1948, at the age of 71, one year after Indian independence and the Partition of India, and a year after all Indian adults were given the right to vote. Throughout her life she used her unique position to fight for others and make a difference.

Records featured in this article

-

- From our collection

- RG 11/1846

- Title

- 1881 census for: Registration Sub-District 2 Lakenheath

- Date

- 1881

-

- From our collection

- WORK 19/315

- Title

- Record of proposed works at Faraday House

- Date

- 1909–1910

-

- From our collection

- ASSI 52/212

- Title

- Court papers on Edgar Whitely, printer of ‘The Suffragette’ newspaper charged for inciting people to join the Women’s Social and Political Union

- Date

- 1913

-

- From our collection

- HO 144/1106/200455

- Title

- Suffragette disturbances at Westminster

- Date

- 1910–1911

-

- From our collection

- HO 45/24665

- Title

- Suffragette index of arrests

- Date

- 1906–1914

-

- From our collection

- RG 14/3561

- Title

- 1911 census for: Registration Sub-District: Hampton Civil Parish

- Date

- 1911

-

- From our collection

- RG 101/2162C

- Title

- 1939 Register Booklet for: Buckinghamshire

- Date

- 1939

Further reading

The National Archives hold various records about Sophia’s life. However, the British Library India Office records hold more personal papers and surveillance on the family.

Find out more about the women’s suffrage movement in Britain through our guide Women's suffrage – The National Archives or on our The fight for the female vote pages.

The Holocaust Memorial Trust website details how Sophia and her sister Catherine helped German-Jewish families escape Nazi persecution.