Important information

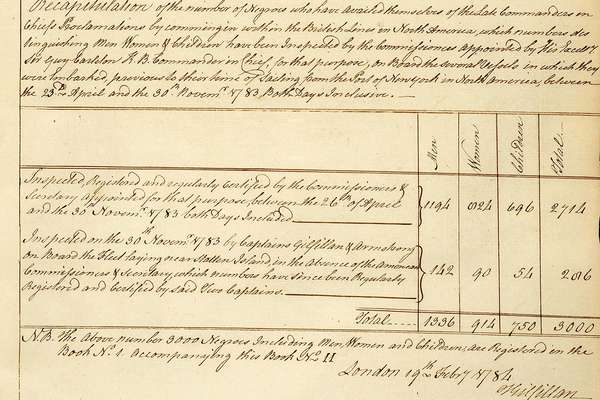

This article contains references to racist abuse and discrimination against Black people and an image with transcript of a document containing racist language. Original language is preserved here to accurately represent our records and to help us fully understand the past.

Early life and cricketing career, 1923–1939

Learie Constantine was born in 1901 in Trinidad, a Caribbean Island that was at that time a part of the British Empire. Following in the footsteps of his father Lebrun Constantine, the grandson of enslaved peoples, Learie found that he excelled in cricket and became part of the West Indies test match team.

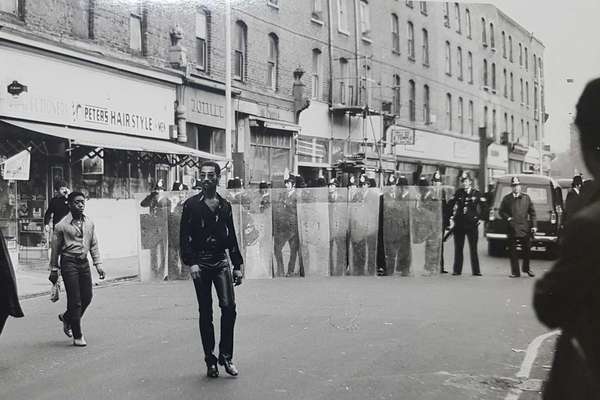

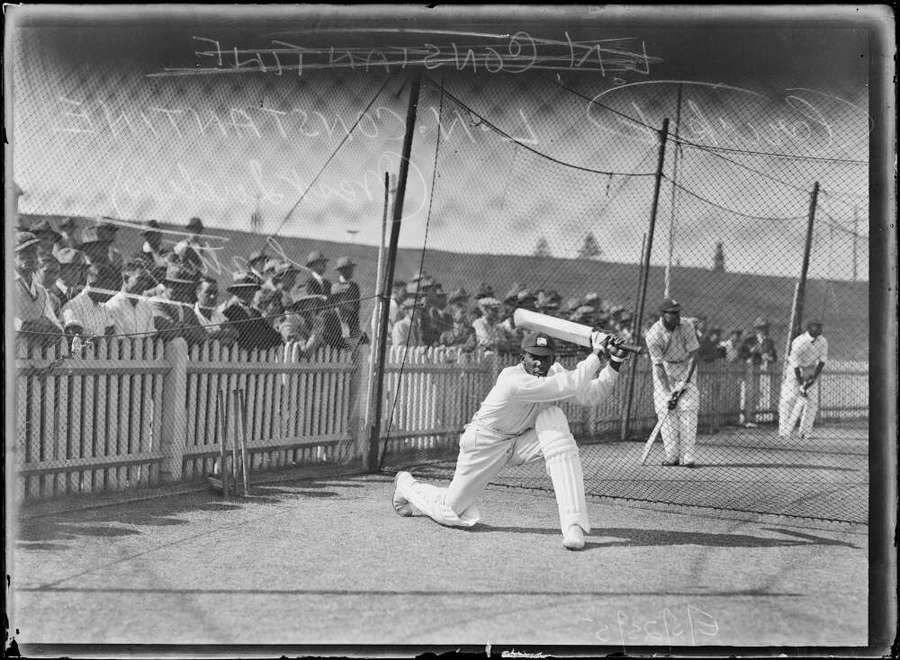

Learie Constantine in New South Wales around 1930, practicing batting in the training nets. Source: The National Library of Australia. The Fairfax archives of glass plate negatives.

The respected cricket correspondent Neville Cardus said of Learie, ’To say that he plays cricket … is to say that a fish goes swimming.’ Although cricket in the Caribbean brought people together, Learie also became aware of the racial and class hierarchy that informed the sport.

In conversation with the intellectual and fellow sportsman C.L.R. James, Learie argued that through cricket, West Indians could show they were able to compete with their white colonial counterparts. James recognised a deeper political statement in his words – the hope of an independent Trinidad and Tobago. Cricket and colonial politics would remain tightly enmeshed throughout the following decades.

Shortly after stunning British audiences in the Middlesex game at Lord’s Cricket ground in 1928, Learie joined Nelson Cricket Club in Lancashire, becoming the first West Indian player in the Lancashire League. He continued to challenge the conventions of the sport on the field and in print.

In the 1930s, Learie joined the League of Coloured Peoples – a British civil rights organisation – and published Cricket and I. This was, the first of several books on cricket that explored the racial attitudes of the game. He stayed at Nelson for nine seasons and became a local hero.

Constantine v Imperial Hotels Ltd, 1943

From 1943, Learie worked for the Ministry of Labour and National Service as a local welfare officer in Liverpool. He also contributed to the BBC radio wartime broadcasting service. It was Learie’s job to ensure the wellbeing of the technicians from the West Indies and West Africa who worked in factories across the midlands.

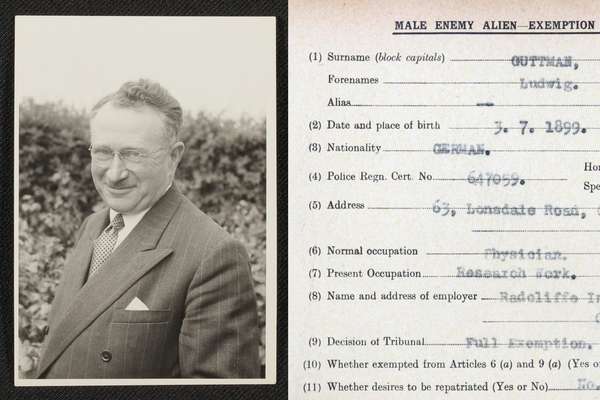

A photo of a group of the West Indian Labour Force of engineers, mechanics and boiler makers at the Ministry of Labour, St. James' Square, London. Learie Constantine is shown to the left of Ernest Bevin (centre), the Minister of Labour. © IWM SG 8615C

However, the arrival of American servicemen in Britain, who were used to segregated leisure spaces, led to increased incidents of racism. These servicemen boycotted leisure spaces open to Black servicemen, causing many difficulties for those Learie was trying to support. Black people also faced discrimination in housing, and were even turned away from religious services.

In July of 1943 Learie, his family, and two friends, were staying at the Imperial Hotel in Bloomsbury in London, when they were told they could only stay one night, despite having booked four nights in advance. The incident was reported on widely in British newspapers as an example of the colour bar in Britain.

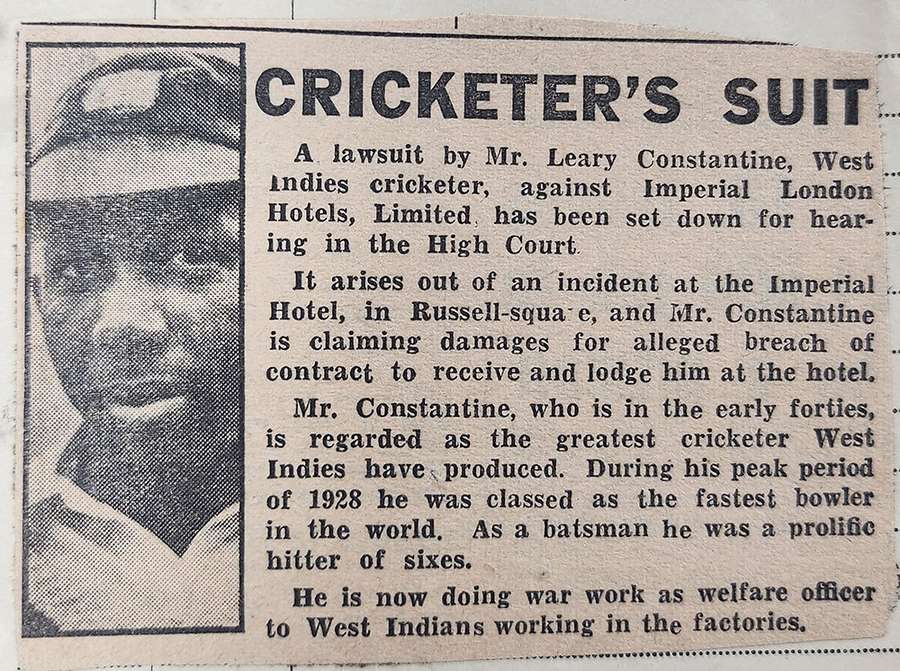

Cricketer’s Suit

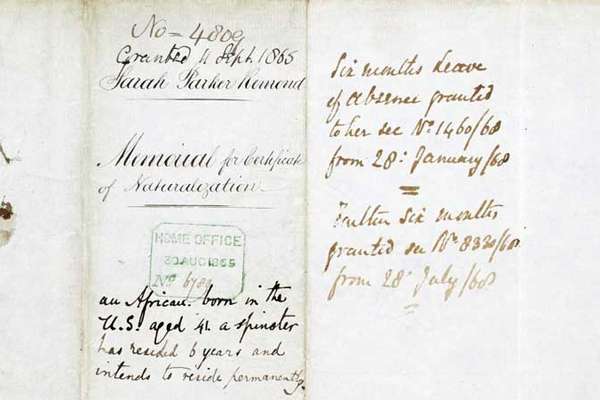

A lawsuit by Mr. Leary Constantine, West Indies cricketer, against Imperial London Hotels, Limited, has been set down for hearing in the High Court.

It arises out of an incident at the Imperial Hotel, in Russell-square, and Mr. Constantine is claiming damages for alleged breach of contract to receive and lodge him at the hotel.

Mr. Constantine, who is in the early forties, is regarded as the greatest cricketer West Indies have produced. During his peak period of 1928 he was classed as the fastest bowler in the world. As a batsman he was a prolific hitter of sixes.

He is now doing war work as welfare officer to West Indians working in the factories.

A cutting from the Daily Mirror, 13 March 1944. Catalogue reference: HO 45/24748

-

- From our collection

- HO 45/24748

- Title

- Home office files on alleged colour bars in hotels and restaurants

- Date

- 1930–1948

A few months later Learie decided to take legal action against Imperial London Hotels Ltd and won nominal damages. The case prompted questions in parliament about making the colour bar in British hotels, bars and restaurants illegal.

Just a year after the Imperial Hotel case, Learie was racially abused in a pub in London and warned in a letter to the Ministry of Labour that the hesitant government approach had a harmful effect on Black Britons and could lead to an individual, ‘to take the law in his own hands’.

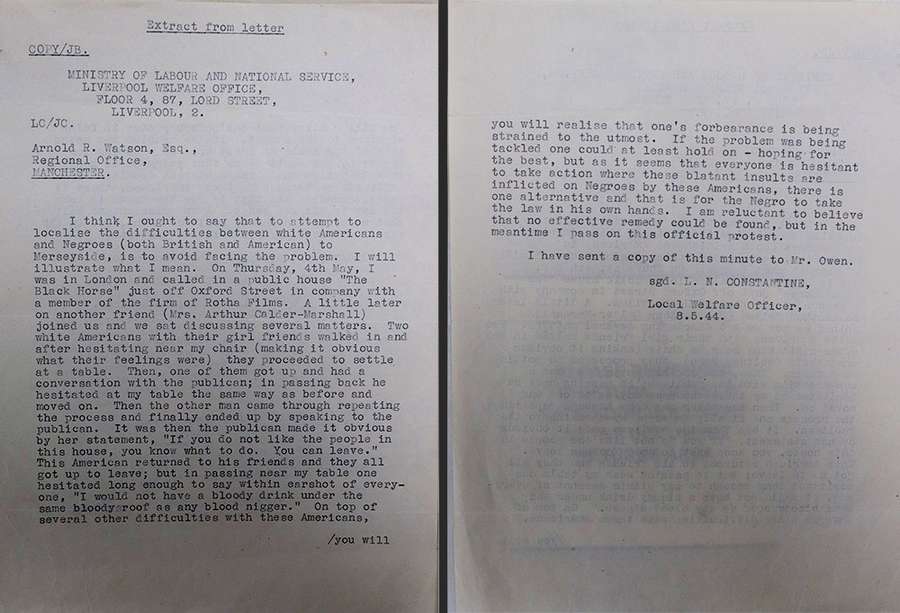

[…] to attempt to localise the difficulties between white Americans and Negroes (both British and American) to Merseyside, is to avoid facing the problem […] On Thursday, 4th May, I was in London and called in a public house “The Black Horse” just off Oxford Street […] Two white Americans with their girl friends walked in and after hesitating near my chair making it obvious what their feelings were they proceeded to settle at a table. Then, one of them got up and had a conversation with the publican; in passing back he hesitated at my table the same way as before and moved on. Then the other man came through repeating the process and finally ended up by speaking to the publican. It was then the publican made it obvious by her statement, “If you do not like the people in this house, you know what to do. You can leave.” This American returned to his friends and they all got up to leave; but in passing near my table one of them hesitated long enough to say within earshot of everyone, “I would not have a bloody drink under the same bloody roof as any blood nigger.” […] If the problem was being tackled one could at least hold on – hoping for the best, but as it seems that everyone is hesitant to take action where these blatant insults are inflicted on Negroes by these Americans, there is one alternative and that is for the Negro to take the law in his own hands. I am reluctant to believe that no effective remedy could be found, but in the meantime I pass on this official protest.

Letter written by Learie Constantine in his role as a local welfare officer for the Ministry of Labour and National Service, dated May 8 1944. Catalogue reference: LAB 26/55

-

- From our collection

- LAB 26/55

- Title

- Accounts of the tensions caused by the barring of black British subjects from dance halls, hotels and clubs due to hostility of white US servicemen

- Date

- 1942–1945

Although Learie was awarded an MBE in 1946 for his ‘welfare work’ during war time, his frustration at the inaction of the government in addressing the colour bar directly was clear.

In 1954, Learie published Colour Bar, a book that criticised not only racial inequality, but also British colonialism and empire. In the same year Learie qualified as a barrister and made the decision to return to Trinidad to pursue law.

To Trinidad and the return to Britain

Yet political life was calling, two years after his return to Trinidad, Learie became a minister for the People’s National Party (PNP) until the country's Independence in 1962. But despite his prominent roles and the high regard in which he was held, when Learie was offered the position of High Commissioner for Trinidad and Tobago in London, a well-paid and respected position, he accepted.

In the years that followed, Learie was awarded a string of accolades and much-respected positions, from a knighthood in 1962 to positions on the Sports Council, the Race Relations Board, and the BBC Board of Governors. But his time in post as High Commissioner was not without controversy.

In April 1963, people in Bristol boycotted the buses for four months, in protest of the discriminatory employment practices of the Bristol Omnibus Company. Learie’s involvement led to tension between himself and his long-tern acquaintance, Eric Williams, the first Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago.

Later that year, when Maltese workers were encouraged to migrate to Britain, Learie’s comments, that the invitation showed the inherent racial bias of the newly passed Commonwealth Immigration Act, received a lot of attention in the British press.

The West Indian Gazette, a publication that was edited by Claudia Jones, argued however that it was within the scope of the High Commissioner to comment on such matters (Catalogue reference: DO 200/81).

-

- From our collection

- DO 200/81

- Title

- Trinidadian High Commission in London: criticisms of Her Majesty's Government

- Date

- 1963

In 1964 amidst much media speculation, Learie resigned.

The Race Relations Act, 1965

The mid-1960s witnessed the proliferation of different groups campaigning for racial equality and justice in Britain, like the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination (CARD). In 1965 the Race Relations Act made discrimination on grounds of colour, race, ethnic, or national origins unlawful.

Learie was appointed to the Race Relations Board (RRB), who considered complaints of discrimination under the act. However, both the Act and the board received harsh criticism. Housing and employment practices were excluded, and the board carried no investigative or punitive powers. It has been argued that the Act even targeted racial justice activists.

The Sri Lankan activist Ambalavaner Sivanandan, claimed that the RRB created ‘a tranche of Black middle-class administrators who would manage racism.’

Becoming the ‘Black Englishman’

Reflecting on Learie Constantine’s impact on British society depends on where you stand; on the cricket field, in a broadcasting studio or in the House of Lords, where Learie was able to sit after becoming a life peer in 1969.

Photographic portrait of Sir Learie Constantine in 1967 by Godfrey Argent. ©National Portrait Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

In a speech to the House in 1971, a few months before he died, he talked about how the West Indian was a ‘Black Englishman’ schooled in British ways and customs. Perhaps it was this approach, that emphasised assimilation, and encouraged arrivals to ‘behave like good guests’, that offended other Black activists.

When the potential peerage first hit the press in 1964, it was criticised by the politician Lionel Seukeran, as it would mean Learie would have to forego his Trinidadian citizenship.

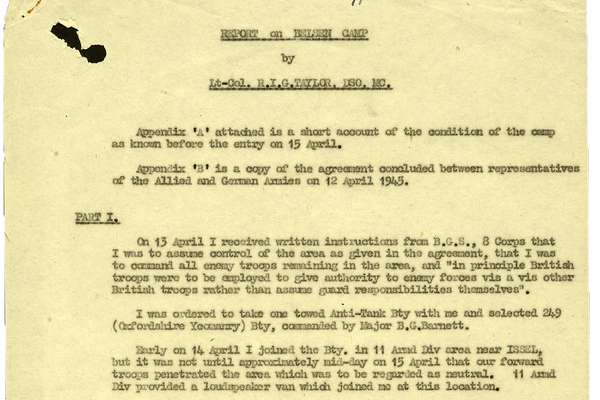

‘Peerage offer is an insult’

Guardian Political reporter

Mr. Lionel Seukeran acting Leader of the Opposition Democratic Labour Party, yesterday joined issue on the reported intention of the British Government to make Sir Learie Constantine a Life Peer.

Mr. Seukeran said it was an insult to ask Trinidad and Tobago to concur with “a decision whereby one of its top citizens would have to renounce his citizenship in favour of a hollow and meaningless honour by a foreign nation.”

He felt that Sir Learie was most competent to decide on the desirability of accepting a British Peerage at the expense of his citizenship.

Mr. Seukeran said that there was more honour in serving West Indian and Trinidad immigrants to England, “to which he professes to be dedicated,” than there was for him to be a Peer.

The DLP Leader said: “If I were Sir Learie, there would be no hesitation in turning down the offer and retaining my Trinidad citizenship, which so many people have striven for several years to obtain and are still striving to make a success.”

He added: “Sir Learie should stop embarrassing the Trinidad Government and other people who have a say in the affairs of this country.”

Mr. Seukeran felt it was time Sir Learie broke “the hushed silence which has pervaded since the announcement, and make up his mind whom shall he serve.”

He said that history was “replete with loyal citizens who have rejected such honours.”

A clipping from the Trinidad Guardian reporting Lionel Seukeran's criticism of Sir Learie Constantine, 21 May 1964. Catalogue reference: DO 200/60

-

- From our collection

- DO 200/260

- Title

- Appointment of Sir Learie Constantine to Race Relations Board

- Date

- 1964

Others felt he could achieve more on the behalf of West Indian migrants outside of the House. Eric Williams even threatened to resign from the Privy Council if Learie was appointed.

Yet, despite their different approaches to racial justice, Learie’s long term friend and acquaintance, C. L. R. James wrote, ‘My dear Learie, I want to put it in writing that while I have no truck whatever with lordships etc, I am very happy to congratulate you...’

Learie wrestled with his identity, caught between the white British establishment, the call of his Trinidadian heritage, and his Blackness. Yet it was only through these different belongings that Learie was able to make impact.

When he died in 1971, he was honoured on both sides of the Atlantic with a state funeral in Trinidad and a memorial service in Westminster Abbey. Such an honour is afforded to few. Learie Constantine represents an important figure in Black British history, well represented in records at The National Archives.

Further reading on Sir Learie Constantine

Kwesi Owusu, ‘The struggle for a radical Black political culture: an interview with A. Sivanandan’, Race and Class, 58, July–September, 2016: 11.

Neville Cardus, 'Learie Constantine's benefit', The Guardian, 8 August 2008 (accessed August 2023).

Read more

Research guide: Black British social and political history in the 20th century

This guide will help you to find records relating to the experience and influence of black British people in the 20th century.

Blog: Black boxers and the colour bar in 20th century Britain

This blog takes a look at sport and particularly boxing as a cultural arena for debates around race and citizenship.