Important information

This article references homophobic attitudes and attempts to repress elements of LGBTQ+ lives. 'LGBTQ+' and 'queer' are used here as umbrella terms to reference lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people.

‘Vague and all encompassing’

On 24 May 1988, in the face of widescale protests from LGBTQ+ activists and allies, the Local Government Act was passed. Within the Act was Section 28 – a seemingly small addition to the earlier Local Government Act 1986. It prohibited local authorities from ‘promoting homosexuality by teaching or by publishing material' and from teaching ‘the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship’. But what did the legislation really mean in practice?

Activist Dan Glass describes Section 28 as ‘simultaneously vague and all encompassing’. Campaigning literature against the introduction of the Act highlighted activists’ fears, that it would:

invalidate employment and housing rights for lesbians and gay men, ban library books by gay authors, threaten hostels for homeless lesbian and gay youths, remove liquor licenses from lesbian and gay establishments, disrupt counselling services, and curtail artistic freedoms. Lesbian and gay groups will lose access to resources and meeting places. AIDS activists are concerned that the measure will foster a homophobic climate that could hinder efforts to halt the AIDS epidemic.

Clause 28 protest leaflet. Catalogue reference: FCO 82/1979

The remit of the Act was actually far narrower than this, however the impact of Section 28 was more than just the legal parameters it set, but also the social climate it created. With the passing of the Act, a landscape of self-censorship was formed, where no one wanted to be the test case for this new law.

Education

Section 28 had no direct jurisdiction over most parts of school life, only the elements run by local authorities. Even the government that introduced the legislation sought to clarify it quickly, with a circular acknowledging ‘that there is a fear of irrational interpretation of these provisions.’

The government circular stated:

It will not prevent the objective discussion of homosexuality in the classroom, nor the counselling of pupils concerned about their sexuality.

Local Government Act: Circular. Catalogue reference: AT 113/4

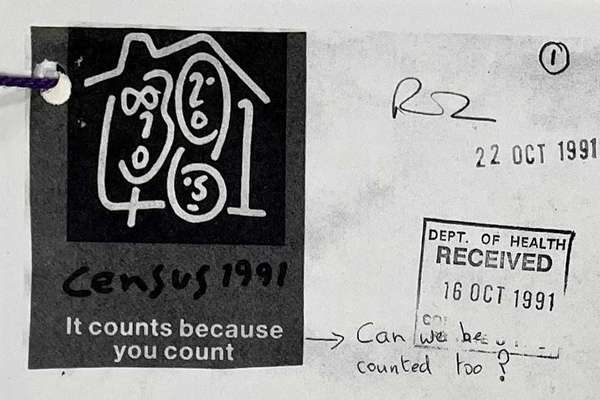

Yet personal testimony of many in the education system shows how fiercely they felt its impact. The campaign group Outrage! quoted a Health Education Authority survey in their correspondence with the government. Of 4,400 young people (aged 16-19) who were surveyed in 1991:

- 45% felt they had not received enough information in school about homosexuality.

- 82% said they had received no information about male homosexuality.

- 86% had received no information about lesbianism.

Outrage! argued the lack of awareness and education in schools ‘perpetuates the isolation, fear and guilt experienced by so many young lesbians and gays’ (catalogue reference: ED 269/482/1).

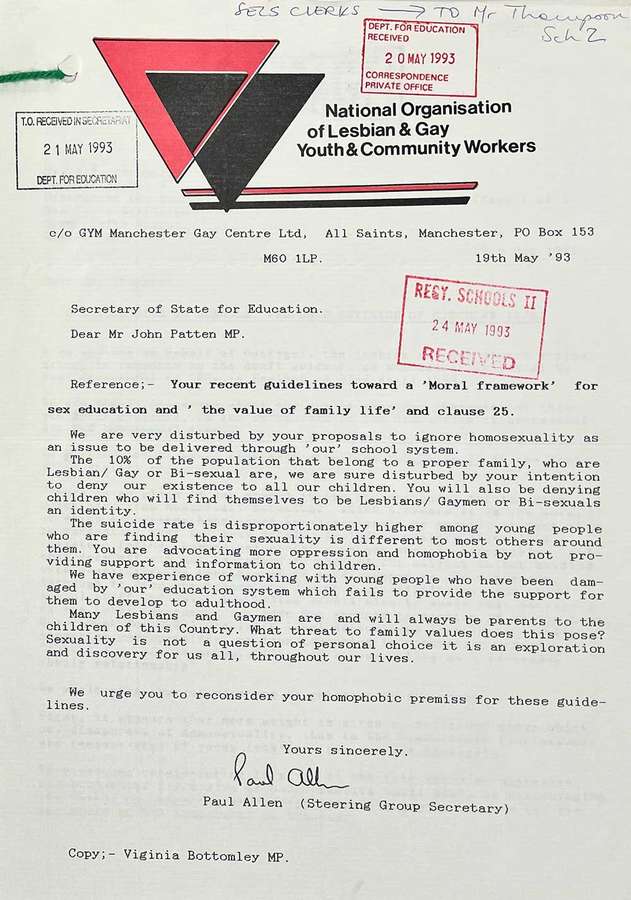

Sex education was a particular area of conflict, as shown in the creation of a Conservative government pamphlet in 1994 – a move described by author Paul Baker as ‘damage control’. Lesbian and gay groups, women’s groups, religious representatives and others were consulted during its production. It made clear Section 28’s specific parameters.

However, Stonewall, Outrage!, the Gay & Lesbian Humanist Association, Lesbians and Gays Working in Education and others, strongly objected to the framing of the pamphlet in terms of traditional family values and marriage, as well as the negative nature of the guidance in relation to homosexuality (catalogue reference: ED 269/482/1).

Secretary of State for Education

Dear Mr John Patten MP.

Reference;- Your recent guidelines toward a ‘Moral framework’ for sex education and ‘the value of family life’ and clause 25.

We are very disturbed by your proposal to ignore homosexuality as an issue to be delivered through ‘our’ social system.

The 10% of the population that belong to a proper family, who are Lesbian/Gay or Bi-sexual are, we are sure disturbed by your intention to deny our existence to all our children. You will also be denying children who will find themselves to be Lesbians/Gaymen or Bi-sexuals an identity.

The suicide rate is disproportionately higher among young people who are finding their sexuality is different to most others around them. You are advocating more oppression and homophobia by not providing support and information to children.

We have experience of working with young people who have been damaged by ‘our’ education system which fails to provide support for them to develop to adulthood.

Many Lesbians and Gaymen are and will always be parents to the children of this Country. What threat to family values does this pose? Sexuality is not a question of personal choice it is an exploration and discovery for us all, throughout our lives.

We urge you to reconsider your homophobic premiss for these guidelines.

Yours sincerely

Paul Allen (Steering Group Secretary)

Copy; - Virginia Bottomley MP

Letter sent to the Department of Education by the National Organisation of Lesbian & Gay Youth & Community Workers expressing their discontent in response to a government sex education circular, 1993. Catalogue reference: ED 269/482/1.

It was not just children who were affected. Between 1937 and 1952, dozens of men and three women had been removed from the teaching profession for homosexual practices (catalogue reference: ED 104/15). The late 20th century was meant to be better, but teachers still felt unable to be themselves at work and unable to offer support on sexuality to their students.

Some teachers turned to activism in their private lives, but author and teacher Catherine Lee also noted many lesbian and gay teachers felt they ‘could not protest because doing so would have jeopardised our careers.’

Teachers’ unions created guidance to help schools navigate the Act, as did LGBTQ+ and civil rights organisations like Liberty, who also issued guidance for voluntary organisations and local authorities.

A worker at Gay’s the Word, the oldest LGBT bookshop in the UK, described how they thrived through the 1990s Section 28 era and often had visits from librarians from Islington, Camden, Wandsworth and Brighton. Several mainly Labour councils also rebelled against the legislation, continuing their pro-equalities work.

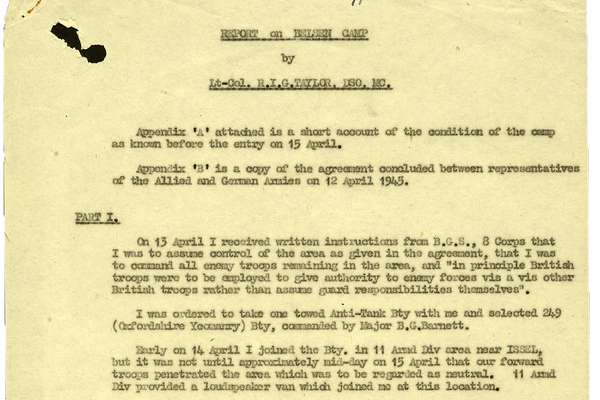

The AIDS crisis

Attempts to educate about homosexuality in schools were linked to general student wellbeing, but were also driven by the AIDS crisis, which disproportionately affected gay men. There was a provision in the Act to lessen Section 28’s impact on health care, and government records show the continuation of AIDS-related educational campaigns.

Education leaflets from pre-1988 were still used in schools, and projects relating to theatre and film were at times able to continue. However, it is hard to know how many ventures were deterred by the fear of the law, or how many programmes had to be changed to fit the Act’s parameters.

Leaflet written in 1987, AIDS Some Questions and Answers: Facts for Teachers, Lecturers and Youth Workers. Catalogue reference: ED 232/21/2

The key impact on AIDS was the stigma the legislation created, in a time where shame and secrecy were already killing people.

Galvanizing a movement

These difficult times prompted a new generation of activists. In 1989, the year after Section 28 became law, Stonewall was founded. Inspired in name by the Stonewall Riots, it was created to address a gap in activism using more traditional political lobbying methods. The group was initially made up of 14 key campaigners including actors Ian McKellen and Michael Cashman, and sexual health activist Lisa Power. Because of Stonewall's methods, it leaves more traces in government records than other LGBTQ+ campaigning groups.

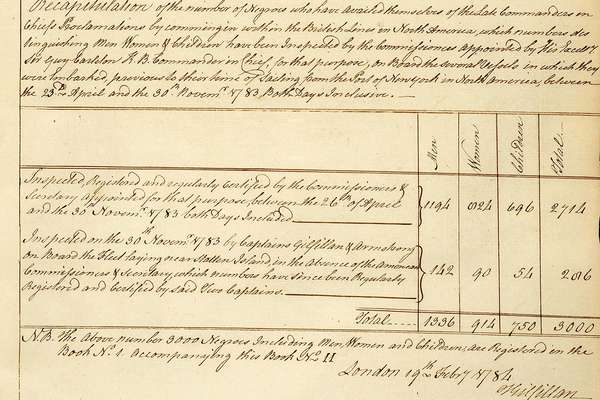

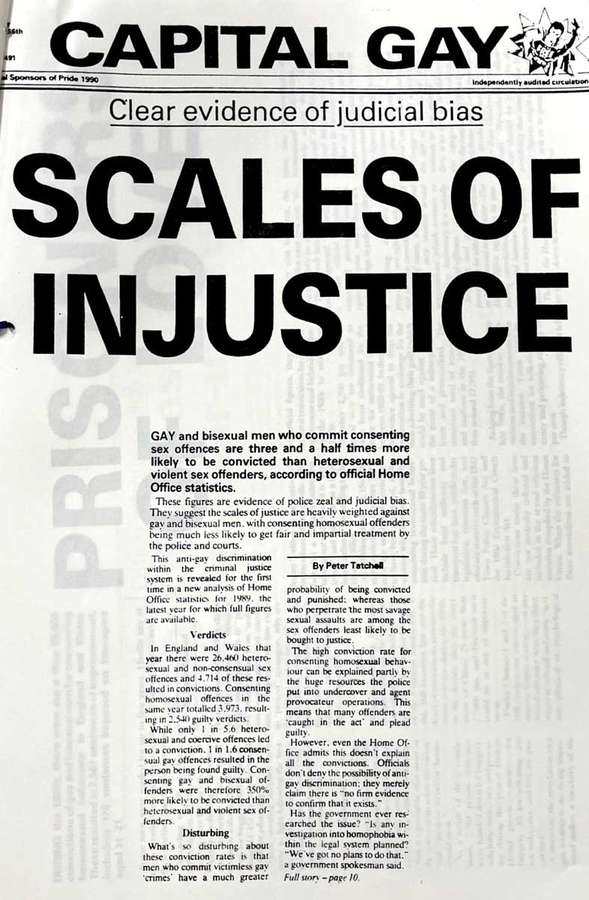

In 1990 Michael Boothe, an actor and gay man, was murdered. The lack of police action emphasised the low priority given to homophobic violence. Outrage! was founded the next day. This organisation, co-founded by Peter Tatchell, had less faith in the democratic system, so used a more creative, direct-action approach. They used various methods from kiss-ins to marches on Parliament and candlelit vigils.

Gay and bisexual men who commit consenting sex offences are three and a half times more likely to be convicted than heterosexual and violent sex offenders, according to official Home Office statistics.

These figures are evidence of police zeal and judicial bias. They suggest the scales of justice are heavily weighted against gay and bisexual men, with consenting homosexual offenders being much less likely to get fair and impartial treatment by the police and courts.

This anti-gay discrimination within the criminal justice system is revealed for the first time in a new analysis of Home Office statistics for 1989, the latest year for which full figures are available.

[…]

While only 1 in 5.6 heterosexual and coercive offences led to a conviction. 1 in 1.6 consensual gay offences resulted in the person being found guilty. Consenting gay and bisexual offenders were therefore 350% more likely to be convicted than heterosexual and violent sex offenders.

[…]

The high conviction rate for consenting homosexual behaviour can be explained partly by the huge resources the police put into undercover and agent provocateur operations. This means that many offenders are ‘caught in the act’ and plead guilty.

However, even the Home Office admits this doesn’t explain all the convictions. Officials don’t deny the possibility of anti-gay discrimination; they merely claim there is “no firm evidence to confirm it exists”

Photocopy of the front cover of Capital Gay, with the headline ‘Scale of Injustice’, highlighting the continued policing of gay men. 1990. The article was written by Peter Tatchell, one of the founders of Outrage! Catalogue reference: HO 528/54.

Other organisations were also created, and women activists were often at the forefront of campaigns. Section 28 was just one front these organisations were fighting on. Other galvanizing issues included the equalising of the age of consent and the over-policing of the gay community.

Playlist: The era of section 28

In the 80s and 90s, music became a vehicle for creative protest and a way to vocalise the many frustrations of the queer community. Listen on Spotify.

Initial intentions

The first nine years of Section 28 were under a Conservative government, but in 1997, Labour won a landslide victory and the era of New Labour under Tony Blair began. The new administration had an explicit equalities agenda, so why did it take a further six years to repeal Section 28?

Labour started their premiership by asserting a commitment to lesbian and gay rights. Records show how closely officials monitored the press reaction to this. Local Government Minister Nick Raynsford made clear the intent to repeal Section 28 just after the Labour victory but noted ‘there is no legislative opportunity available at present’ (catalogue reference: AT 113/15). This was a recurring theme in the attempts to repeal.

Equalising the age of consent was a key issue, championed early on by Home Secretary Jack Straw. Section 28 was considered to be more politically sensitive, described in government files as a ‘controversial and emotive subject’ (catalogue reference: AT 113/15).

The Department of Transport, Local Government and the Regions and the Department for Education ‘received a steady flow of correspondence from members of the public, fairly equally split between those pressing for repeal, and those worried that it may be’ (catalogue reference: AT 113/15). The government created stock responses to clarify their position.

Parliamentary questions also applied pressure, especially from the Liberal Democrats.

Cautious parliamentary attempts

By 2000 the government was tackling the issue more directly and tried several different approaches. One was through the Learning and Skills Bill, another was through a new Local Government Bill. But Labour knew including Section 28 repeal in these pieces of legislation risked derailing them altogether. The parliamentary backlash to these approaches, particularly with the Lords, led them to be dropped.

Even supporters of repeal were concerned about the electorate’s reaction. David Blunkett, Secretary of State for Education and Employment, wrote in a letter to Tony Blair :

we appear to be in real danger of getting on the wrong side of the argument in relation to the family… I am very worried that the people I know and care about, who are on the margins of politics and who are classic voters in their 40s and 50s, are a little bit confused about what messages we are putting out .

Letter from David Blunkett to Tony Blair. Catalogue reference: PREM 49/1408

With an impending general election, tensions were high about not alienating voters and not making this a defining electoral issue that might also galvanise Section 28 supporters (catalogue reference: PREM 49/1408).

In the meantime, Stonewall sought legal advice about Section 28. Angela Mason, their director at this time, shared this advice with the Prime Minister. The law firm Bindman and Partners felt there was the potential to challenge Section 28 under the Human Rights Act 1998 (which would come in to force October 2000). They also saw the potential for a judicial review with Stonewall as the plaintiff, showing how the legislation negatively impacted their work (catalogue reference: PREM 49/882).

Scotland

Meanwhile the situation in Scotland was progressing at a faster pace. In late 1999, the Scottish Parliament sought legal advice on whether it was legislatively possible for them to repeal Section 2A (as Section 28 was known in Scotland) separately from the wider British Government (catalogue reference: PREM 49/1408).

Brian Souter was a businessman, financier and figurehead behind the Scottish pro-Section 28 campaign. He wrote to the government in early 2000 expressing his outrage at an education pack which was commissioned by Avon Health Authority for secondary schools as part of the HIV prevention program. Developed in consultation with teachers, Beyond a Phase aimed to help young lesbian and gay people feel less ‘invisible in their schools’. Souter claimed it encouraged ‘homosexual roleplay’. He went on to fund a ‘Keep the clause’ vote in Scotland, with ballots sent to every home.

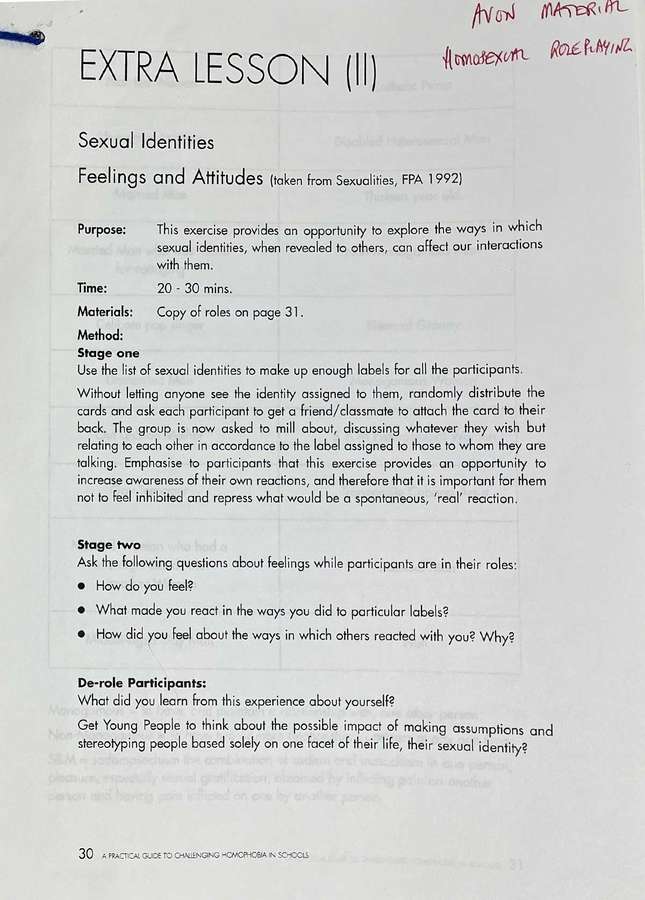

Extra Lesson (II)

Sexual Identities

Feelings and Attitudes (taken from Sexualities, FPA 1992)

Purpose: This exercise provides an opportunity to explore the ways in which sexual identities, when revealed to others, can affect our interactions with them.

Time: 20 – 30 mins.

Materials: Copy of roles on page 31

Method:

Stage One

Use the list of sexual identities to make up enough labels for all the participants.

Without letting anyone see the identity assigned to them, randomly distribute the cards and ask each participant to get a friend/classmate to attach the card to their back. The group is now asked to mill about, discussing whatever they wish but relating to each other in accordance to the label assigned to those to whom they are talking. Emphasise to participants that this exercise provides an opportunity to increase awareness of their own reactions, and therefore it is important for them not to feel inhibited and repress what would be a spontaneous, ‘real’ reaction.

Stage two

Ask the following questions about feelings while participants are in their roles:

- How do you feel?

- What made you react in the ways you did to particular labels?

- How did you feel about the ways in which others reacted with you? Why?

De-role Participants:

What did you learn from this experience about yourself?

Get Young People to think about the possible impact of making assumptions and stereotyping people based solely on one facet of their life, their sexual identity?

Lesson extract from Beyond a Phase education pack, annotated with the words ‘homosexual role playing’. Catalogue reference: PREM 49/1408.

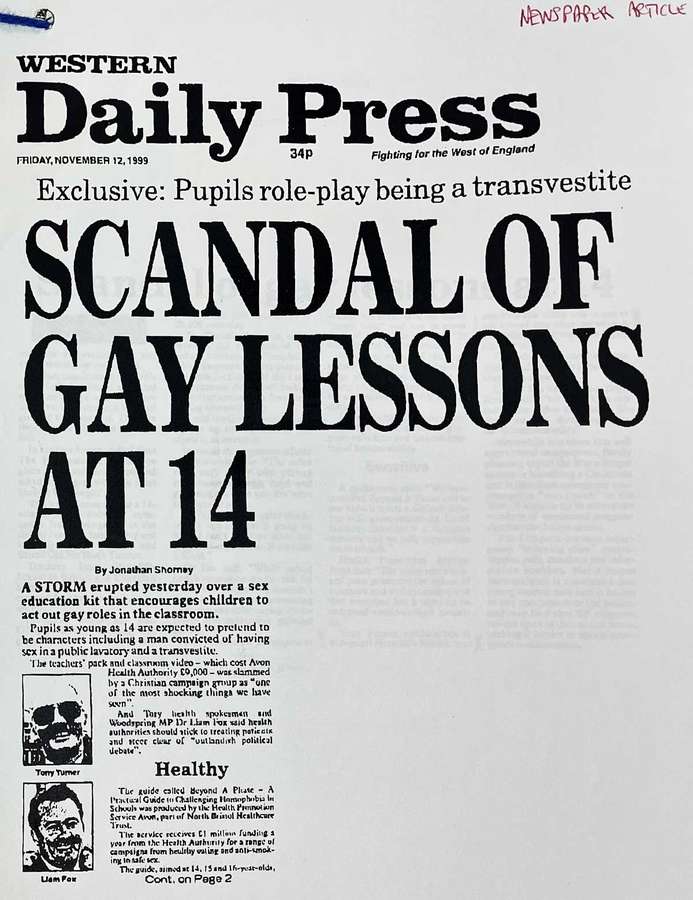

Exclusive: Pupils role-play being a transvestite

Scandal of gay lessons at 14

By Jonathan Shomey

A storm erupted yesterday over a sex education kit that encourages children to act out gay roles in the classroom.

Pupils as young as 14 are expected to pretend to be characters including a man convicted of having sex in a public lavatory and a transvestite.

The teachers’ pack and classroom video – which cost Avon Health Authority £9,000 – was slammed by a Christian campaign group as “one of the most shocking things we have seen”.

And Tory health spokesman and Woodspring MP Dr Liam Fox said health authorities should stick to treating patients and steer clear of “outlandish political debate”.

Healthy

The guide called Beyond a Phase – A Practical Guide to Challenging Homophobia in Schools was produced by the Health Promotion Service Avon, part of North Bristol Healthcare Trust.

The service receives £1million funding a year from the Health Authority for a range of campaigns from healthy eating and anti-smoking to safe sex.

The guide, aimed at 14, 15 and 16-year-olds,

Cont. on Page 2

A photocopy of a front page story in the Western Daily Press about the Beyond a Phase education pack. Catalogue reference: PREM 49/1408.

The overwhelming result was to retain the section, but the ballot count was very low. Government records on Section 28 noted, ‘The situation up North is grim’.

In May 2000 a rare court challenge came from a parent in Scotland concerned about her daughter accessing a pamphlet called Gay Sex Now. The case was championed by the Christian Institute but settled out of court after a compromise was found between the local council and the individual.

Despite the campaigns of Souter and others, the Scottish legislation was repealed by a majority vote of Members of the Scottish Parliament under the Ethical Standards in Public Life Act 2000. A significant victory for lesbian, gay and bisexual people (catalogue reference: PREM 49/1408).

Repeal

During this time, the Prime Minister’s Office was discussing topics such as LGBTQ+ discrimination in the workplace and the legal recognition of trans people. Labour had legislative success with the removal on restrictions of LGBTQ+ service personnel, and finally equalised the age of consent through a rare use of the Parliament Act to get it through the Lords. The lack of public backlash to these changes was encouraging.

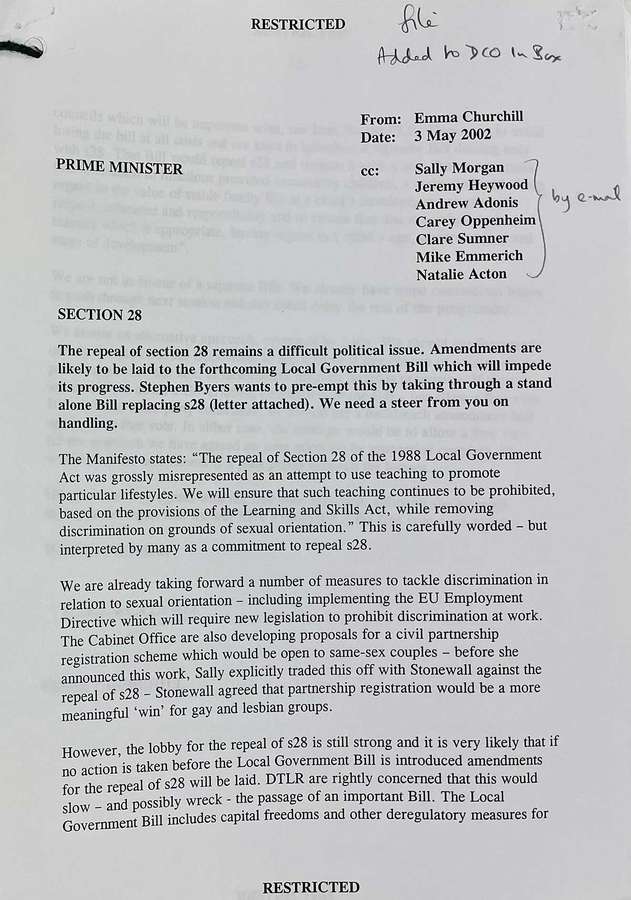

By 2002, the Cabinet Office was developing proposals for a civil partnership registration scheme for same-sex couples. The government bargained with Stonewall on prioritising this over Section 28 repeal: ‘Stonewall agreed that partnership registration would be a more meaningful ‘win’ for gay and lesbian groups.’ (catalogue reference: PREM 49/2698).

The repeal of section 28 remains a difficult political issue. Amendments are likely to be laid to the forthcoming Local Government Bill which will impede its progress. Stephen Byers wants to pre-empt this by taking through a stand alone Bill replacing s28 (letter attached).

[…]

The Manifesto states: “The repeal of Section 28 of the 1988 Local Government Act was grossly misrepresented as an attempt to use teaching to promote particular lifestyles. We will ensure that such teaching continues to be prohibited, based on the provisions of the Learning and Skills Act, while removing discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation.” This is carefully worded – but interpreted by many as a commitment to repeal s28.

We are already taking forward a number of measures to tackle discrimination in relation to sexual orientation […]. The Cabinet Office are also developing proposals for a civil partnership registration scheme which would be open to same-sex couples – before she announced this work, Sally explicitly traded this off with Stonewall against the repeal of s28 – Stonewall agreed that the partnership registration would be a more meaningful ‘win’ for gay and lesbian groups.

However, the lobby for the repeal of s28 is still strong and it is very likely that if no action is taken before the Local Government Bill is introduced amendments for the repeal of s28 will be laid. DTLR are rightly concerned that this would slow – and possibly wreck the passage of an important Bill. […]

Briefing to the Prime Minister on the parliamentary approach to take on Section 28, highlighting the role of Stonewall. Catalogue reference: PREM 49/2698.

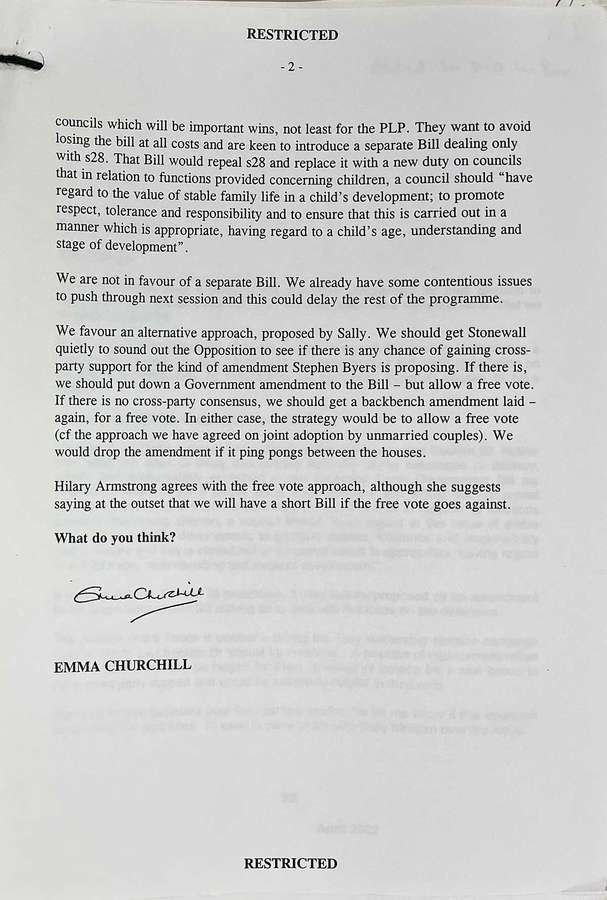

[Department for Transport, Local Government and the Regions] want to avoid losing the [Local Government Bill] at all costs and are keen to introduce a separate Bill dealing only with s28. The Bill would repeal s28 and replace it with a new duty on councils that in relation to functions provided concerning children, a council should “have regard to the value of stable family life in a child’s development; to promote respect, tolerance and responsibility, and to ensure that this is carried out in a manner which is appropriate, having regard to a child’s age, understanding and stage of development”.

We are not in favour of a separate Bill. We already have some contentious issues to push through next session and this could delay the rest of the programme.

We favour an alternative approach, proposed by Sally. We should get Stonewall quietly to sound out the Opposition to see if there is any chance of gaining cross-party support for the kind of amendment Stephen Byers is proposing. If there is, we should put down a Government amendment to the Bill – but allow a free vote. If there is no cross-party consensus, we should get a backbench amendment laid – again, for a free vote. In either case, the strategy would be to allow a free vote (cf the approach we have agreed on joint adoption by unmarried couples). We would drop the amendment if it ping pongs between the houses.

[...]

What do you think?

The second page of the briefing. Catalogue reference: PREM 49/2698.

Some LGBTQ+ rights groups were less keen to prioritise legislation that supported traditional, heterosexual structure. Meanwhile some activists feared that repeal would do very little, and what was needed was proactive anti-homophobia legislation.

Despite this progress, Section 28 was still on the statute book and continued to be referred to as a ‘difficult political issue.’ The legislation held symbolic power, representing Thatcher’s premiership and conservativism. But these legislative shifts were changing the landscape in which Section 28 was being discussed, making it look outdated.

Following the government’s previous failed attempts to progress the issue, it was suggested to approach Stonewall to discreetly scope out the possibility of getting cross-party support for an amendment and free vote (catalogue reference: PREM 49/2698).

A backbench, cross-party amendment to be added to the Local Government Bill 2003 was introduced by Liberal Democrat MP Ed Davey. Conservative leader Iain Duncan Smith offered a free vote.

The vote passed. The next challenge was the House of Lords, where the repeal was championed by openly gay Labour peer, Lord Waheed Alli. After a series of debates and amendments it passed by 180 to 130. Section 2A of the Local Government Act 1986, the legislation which had been inserted by Section 28, would finally be repealed.

Section 2A of the Local Government Act 1986 (c. 10) (local authorities prohibited from promoting homosexuality) ceases to have effect.

Amendment to the Local Government Bill 2003

After all the negativity and fear the Act had created, it was a unified approach that had defeated it. As of 18 November 2003, Section 28 was wiped from the statute book – no longer casting a shadow over lesbian, gay and bisexual lives in England, Wales and Scotland. Just like the original section, it was a few lines in a much broader Act that was to have a huge impact on many lives.

There were never any prosecutions under Section 28. It has been described by cultural historian Matt Cook, as ‘virtually unworkable’. Legally the impact was minimal to non-existent, but socially it cultivated an atmosphere of fear and shame and denied a generation of queer people the visibility and support they deserved.

The legislation is gone, but its legacy lives on in the activism and fight that it galvanised.

Records featured in this article

-

- From our collection

- FCO 82/1979

- Title

- Opposition to Clause 28 of the Local Government Bill 1988 by UK expatriates in the USA

- Date

- 1988

-

- From our collection

- AT 113/4

- Title

- Government circular about Section 28

- Date

- 1988

-

- From our collection

- ED 269/482/1

- Title

- Files relating to government pamphlet on sex education

- Date

- 1993

-

- From our collection

- ED 104/15

- Title

- Submission by Ministry of Education to Home Office departmental Committee of evidence concerning law and practice relating to homosexual offences

- Date

- 1950-1956

-

- From our collection

- ED 232/21/2

- Title

- AIDS some questions and answers: Facts for teachers, lecturers and youth workers

- Date

- 1987

-

- From our collection

- HO 528/54

- Title

- Police operations against crime: Metropolitan Police and homosexuals

- Date

- 1990-1992

-

- From our collection

- AT 113/15

- Title

- Policy on repeal of Section 28

- Date

- 1997

References

- Paul Baker, Outrageous!: The Story of Section 28 and Britain’s Battle for LGBT Education (London, 2022).

- Madeleine Colvin and Jane Hawksley, Section 28: A Practical Guide to the Law and its Implications (London, 1989).

- Matt Cook, A Gay History of Britain: Love and Sex between Men since the Middle Ages (Oxford, 2007).

- Dan Glass, United Queerdom: From the Legends of the Gay Liberation Front to the Queers of Tomorrow (London, 2020).

- Catherine Lee, Pretended Schools and Section 28 : Historical, Cultural and Personal Perspectives (Woodbridge, 2003).

All works referenced are available in The National Archives Library