Record revealed

Secret letter sent to British Secret Services

During the Second World War, some British prisoners of war were able to send and receive secret messages and intelligence. This document shows one of the creative ways these messages were concealed to avoid detection.

Images

Image 1 of 2

A photograph of prisoner of war Guy Griffiths in front of a hidden message written on tracing paper and placed between the back of the photograph and its paper backing. The photograph is 14cm long and 9cm wide.

Image 2 of 2

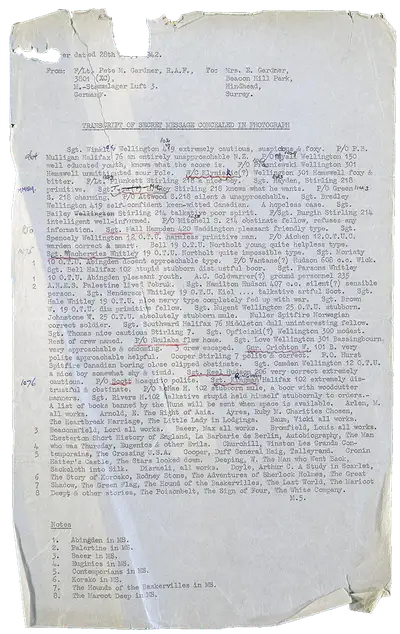

A typed transcript of the hidden message. It contains information about individuals held in POW camp Stalag Luft III, including quite candid descriptions of their personalities.

Partial transcript

Transcript of secret message concealed in photograph...

[Assessments of individuals, including:]

Sgt. Roy Stirling 218 knows what he wants.

P/O Green S. 218 charming.

P/O Attwood S. 218 silent & unapproachable.

Sgt Bradley Wellington 419 self-confident keen-witted Canadian. A hopeless case....

Sgt. Hamilton Hudson 407 c.c. silent (?) sensible person.

Sgt. Henderson Whitley 19 O.T.U Kiel.... talkative artful Scot.

Sgt. Hale Whitley 19 O.T.U nice nervy type completely fed up with war.

Why this record matters

- Date

- 28 July 1942

- Catalogue reference

- AIR 40/2622

Allied Intelligence Services such as MI9 were keen to ensure they could both send and receive messages to and from prisoners of war (POWs) held in Europe. They trained combatants on escape and evasion behind enemy lines, but also taught useful skills should anyone find themselves captured, including sending secret messages back home.

One method adopted by POWs was to conceal intelligence behind photographs. This example was one of many by Flight Lieutenant Peter Gardner, Royal Air Force, from POW camp Stalag Luft III – the setting of the 1963 film The Great Escape – to his mother, who passed them on to British Intelligence Services.

The photograph is not of Gardner but of another member of the camp, Guy Griffiths, who, as he says in the letter, had been at school with Gardner. Griffiths also had an interesting intelligence role in the camp – he was an accomplished artist and would draw fake Allied aircraft and leave them lying around for the guards to find. He would also discuss German aircraft capabilities with the guards so that intelligence might be sent back to the UK.

The text of the hidden messages was written on tracing paper and placed between the back of the photograph and its paper backing, which was then carefully secured back together. It was hoped that even if the letter was opened by the guards, they would not notice that the photograph had been tampered with in this way. This example went undetected.

As the text of the letter was so small, it would have to be magnified and then transcribed by the recipients. The letters would often contain information about individuals held in the camp, including quite candid descriptions of their personalities. In this example, this included descriptions such as ‘silent and approachable’, ‘talkative artful Scot’, and ‘dull uninteresting fellow’, and these depictions were used to assess suitability for further intelligence work within the camp.

As Stalag Luft III was a POW camp for air force officers, the letter contains information about the fate of the crews who flew with some of the individuals when they were shot down. It also contains some coded information and a list of banned books, including Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes novels.

This letter is one of many examples of the kinds of intelligence activities carried out by POWs when in captivity that can be found in our collection.