Early life and the RAF

Roger was born on 30 August 1910 in the mining town of Springs, South Africa. His parents were Benjamin, a mine manager, and Dorothy, who had migrated from Britain before Roger’s birth. At the age of 13 Bushell was sent to school in England, where he excelled in many pursuits, including languages, and played rugby for the school's first team.

Initially destined to join his father in the mining industry, he applied to study engineering at university, but was not keen on following in his father’s footsteps. This was in no small part because he was claustrophobic – remarkable given the number of escapes he would go on to make through tunnels as a prisoner of war (POW).

Eventually he went to Cambridge to study law, hoping to become a barrister, where he graduated in 1932. He was called to the Bar in 1934 and quickly established himself as a capable criminal barrister. While studying, Bushell also developed an interest in flying, and, in 1932, joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) Auxiliary and Reserve Volunteers. He was assigned to 601 Squadron, known as the ‘Millionaires’ Squadron’, as it had been established by a group of wealthy young aviators.

Propaganda postcard showing Spitfires in formation, 1940. Catalogue reference: CN 11/6 (98)

Bushell joined 601 Squadron upon the outbreak of war in September 1939. He was quickly promoted to the rank of squadron leader, where he was ordered to reform 92 Squadron, and gained a reputation as an autocratic leader with impeccable organisational skills.

A prisoner of war

Bushell would not see combat until 23 May 1940. It turned out to be his only time. Leading his squadron’s Spitfires on patrol duties over the French coast, covering the Allied retreat towards Dunkirk, his aircraft were attacked by eight Messerschmitt 109s.

Surviving this engagement, Bushell’s squadron continued its fight throughout the day. After claiming to have shot down two German aircraft, he was eventually hit, and his Spitfire caught fire. Attempting to land in what he thought was friendly territory, he was quickly picked up by German forces once on the ground.

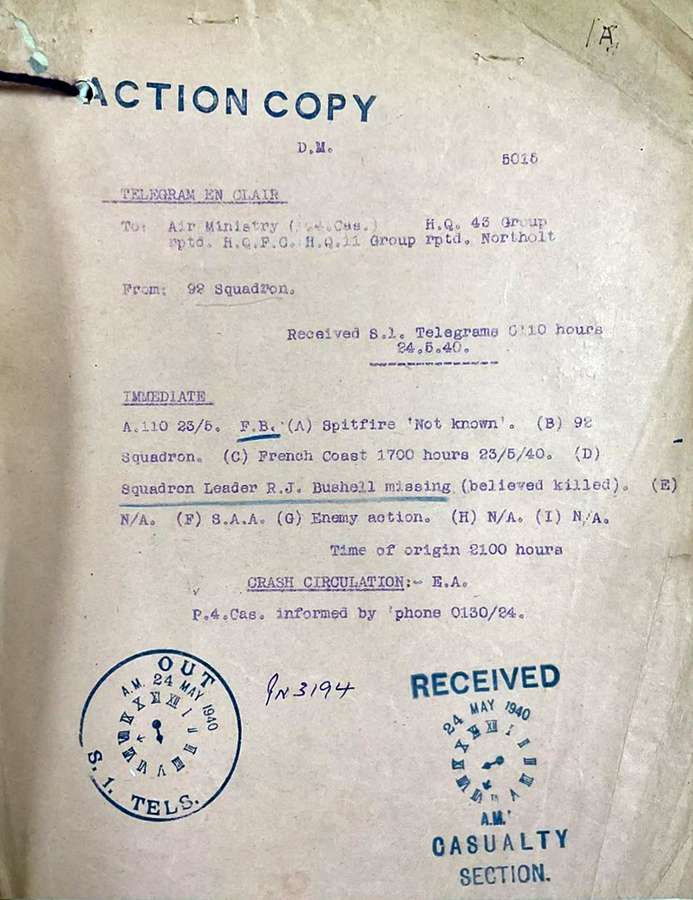

Telegram reporting Bushell as missing (believed killed), 24 May 1940. Catalogue reference: AIR 81/507

Initially Bushell was reported by his squadron as missing, believed killed, and this information was reported to the British authorities. He was sent to Dulag Luft, a transit camp for POWs to be processed before being sent on to other camps. Here he met other POWs who would come to be crucial in the planning of the escape from Stalag Luft III in March 1944.

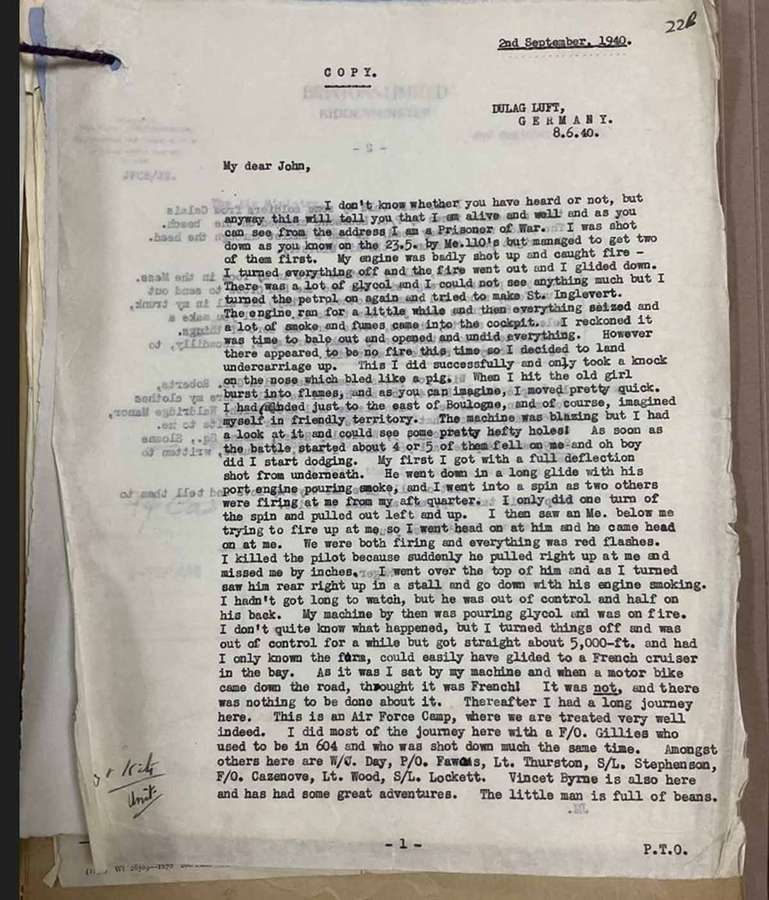

Two weeks after his initial capture, he was able to write to friends and family, confirming that he had not been killed. He told them, ‘I am alive and well and as you can see from the address I am a prisoner of War’.

My dear John,

I don't know whether you have heard or not, but anyway this will tell you that I am alive and well and as you can see from the address I am a Prisoner of War. I was shot down as you know on the 23.5. by Me.110's [Messerschmitts, German fighter planes] but managed to get two of them first. My engine was badly shot up and caught fire – I turned everything off and the fire went out and I glided down...

...I don't quite know what happened, but I turned things off and was out of control for a while but got straight about 5,000-ft. and had I only known the form, could easily have glided to a French cruiser in the bay. As it was I sat by my machine and when a motor bike came down the road, thought it was French! It was not, and there was nothing to be done about it. Thereafter I had a long journey here. This is an Air Force Camp, where we are treated very well indeed...

Letter from Bushell to his brother John from Dulag Luft POW Camp, 8 June 1940. Catalogue reference: AIR 81/507

First escape attempts

It quickly became apparent to those around him that Bushell was focused on escape. His first escape occurred in June 1941: he made it to within a few hundred yards of the Swiss border, and freedom, before being stopped by German guards.

Once recaptured he was soon sent to Oflag VI-B, only to escape from there with a fellow officer Jaroslav Zafouk, a Czech pilot, in October the same year. They made their way to Prague, where they were hidden for nearly eight months before their location was betrayed.

Bushell was initially questioned by the Gestapo, the German secret police, and warned that if he attempted to escape again he would be executed. From there he was sent to Stalag Luft III, near what is now the Polish town of Żagań, arriving in late May 1942.

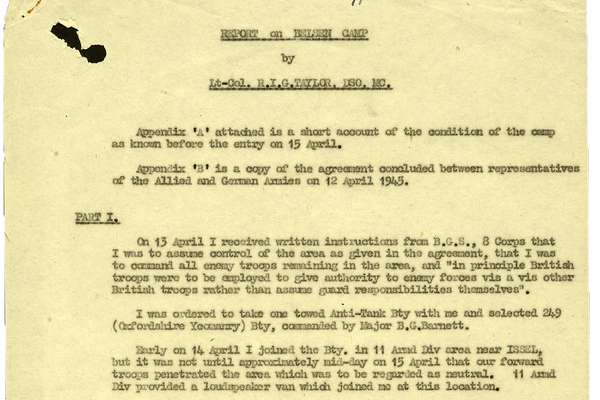

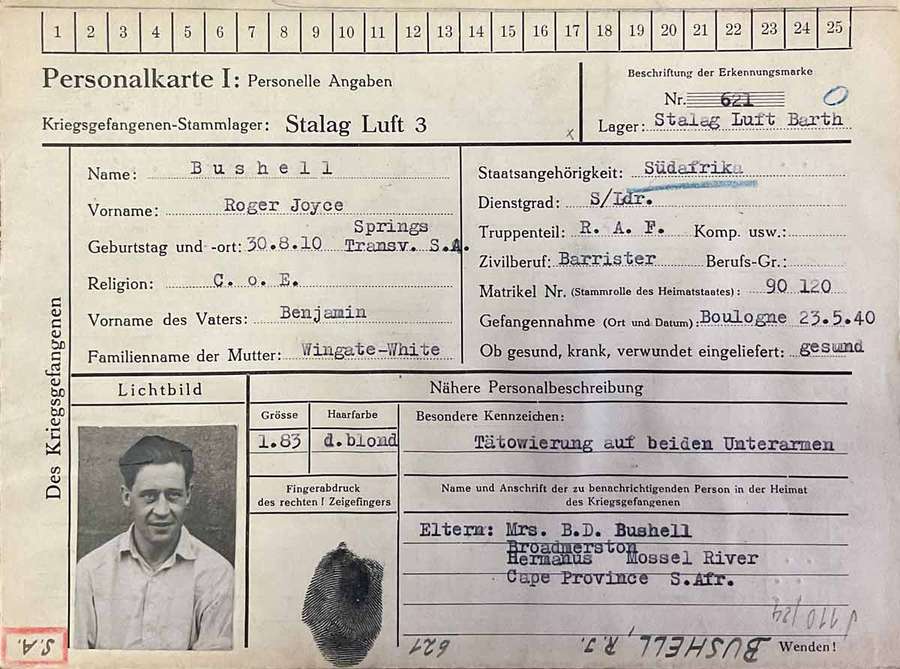

Roger Bushell’s POW Card, issued by Germany. Catalogue reference: WO 416/47/197

The ‘Great Escape’

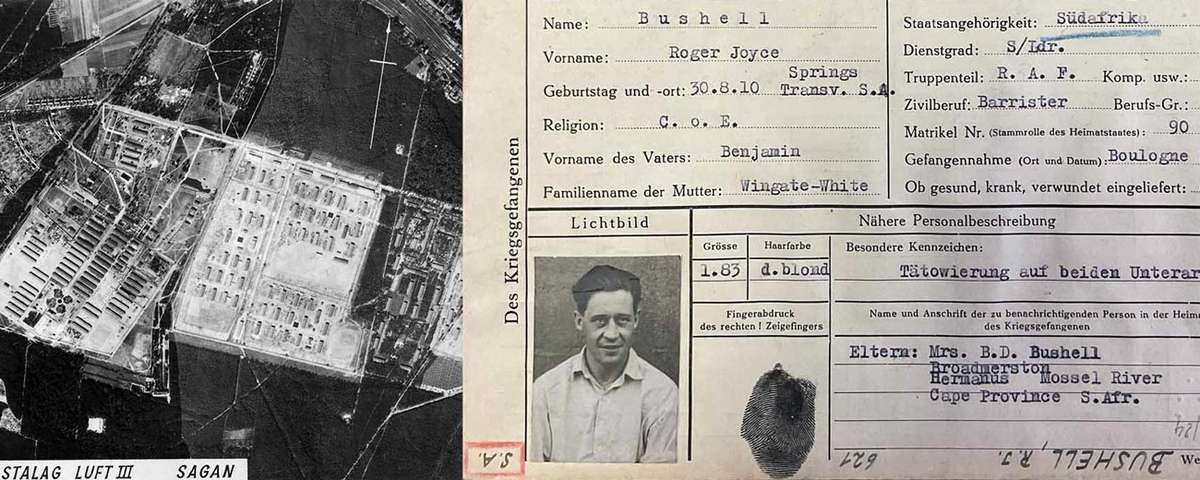

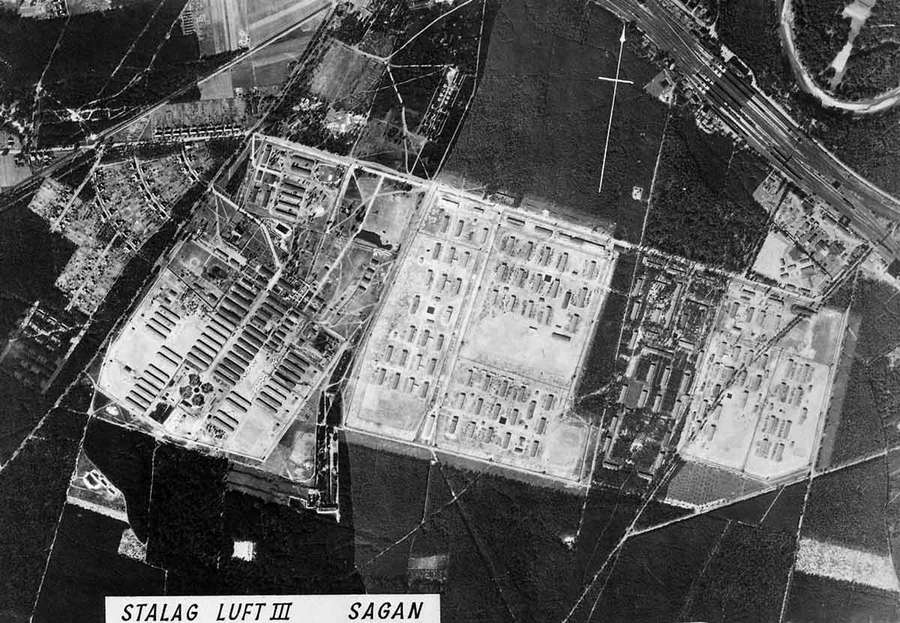

Purpose-built and opened in March 1942, Stalag Luft III was designed to be as hard as possible to escape from. It was built in the middle of a pine forest with a clearing all the way around its barbed-wire compound, located on sandy soil which, it was thought, would make the digging of tunnels impossible. As an added precaution, the barrack buildings were even built on stilts, to help stop inmates from digging tunnels.

Aerial photo of Stalag Luft III dated 1942–1945. Catalogue reference: AIR 40/229

Undeterred, Bushell and his fellow POWs set to work on a plan to escape in this way. Many POW camps formed escape committees to establish escape plans, and the one at Stalag Luft III – with Roger taking the lead – set about building no fewer than three tunnels. They were codenamed Tom, Dick, and Harry. The idea was that if one or even two tunnels were discovered, the German guards would not have thought that there could be a third.

The plans involved hundreds of POWs digging the tunnels, depositing the soil, creating fake identification, making clothes, and generally distracting from suspicious activities. Theatre performances were put on to disguise any noise being made while the tunnels were dug.

Squadron Leaders Robert Stanford Tuck and Roger Bushell (right) in Stalag Luft III. From the Imperial War Museum collection © IWM HU 1605

On the night of 24 March 1944, 200 POWs, each chosen and assigned a number for the order in which they would escape, began to make their way through the tunnel named ‘Harry’. No fewer than 76 of them made it through, three having been arrested at the mouth of the tunnel upon their emergence outside the camp compound.

Bushell was the fourth officer out of the tunnel, and quickly made his way to Sagan railway station with his escape partner, Bernard Scheidhauer. The plan was to catch a train to Alsace, but on 26 March both were stopped and arrested at Saarbrucken station in western Germany, 500 miles from Stalag Luft III.

Initially held in a civilian jail, the Gestapo soon took Bushell and Scheidhauer for what it called ‘political interrogation’. Told that they would then be returned to Stalag Luft III, while travelling by car on 29 March the journey was halted on the autobahn outside Ramstein, Germany. Here, both men were murdered on the side of the road by the Gestapo officers escorting them. The official German report stated that they had ‘been shot while attempting to escape’, though there was no subsequent evidence that this had been the case. Roger was 33 years old.

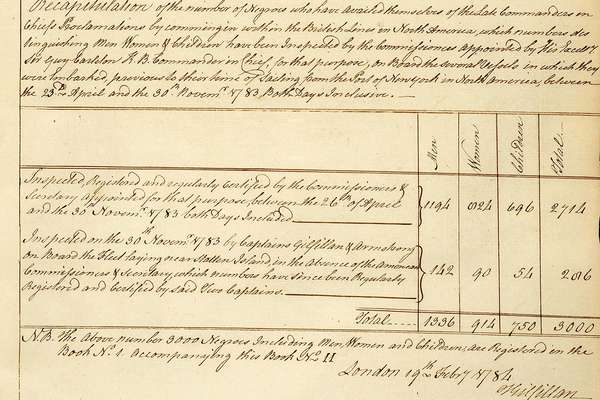

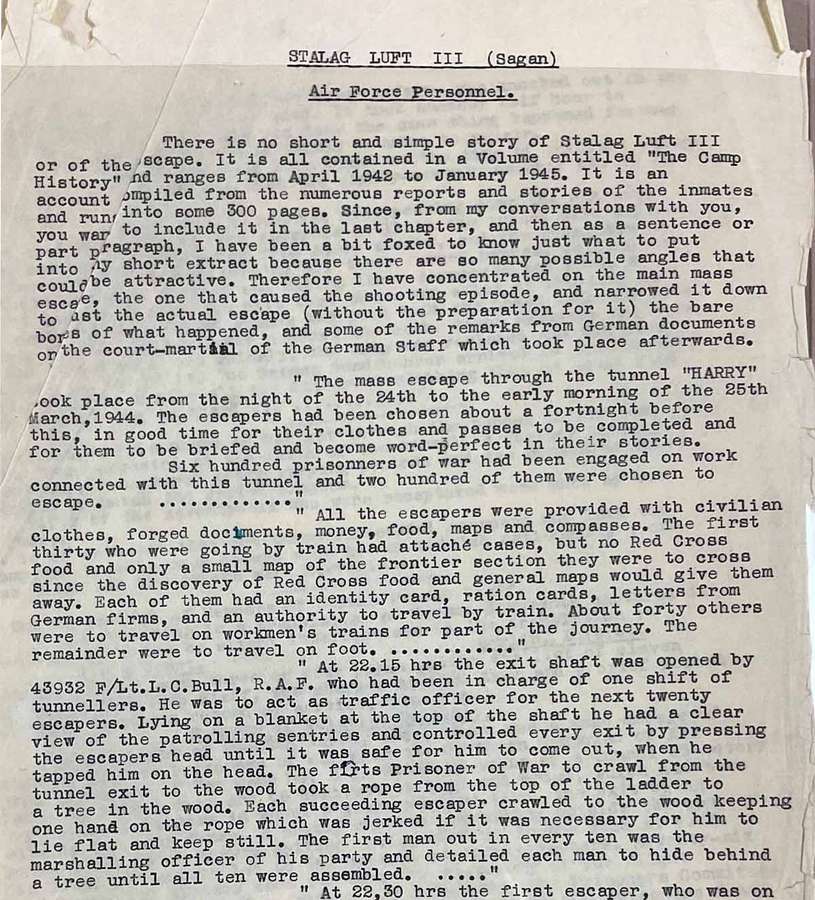

There is no short and simple story of Stalag Luft III or of the escape. It is all contained in a Volume entitled "The Camp History" and ranges from April 1942 to January 1945. It is an account complied from the numerous reports and stories of the inmates and runs into some 300 pages...

"The mass escape through the tunnel "HARRY" took place from the night of the 24th to the early morning of the 25th March, 1944. The escapers had been chosen about a fortnight before this, in good time for their clothes and passes to be completed and for them to be briefed and become word-perfect in their stories.

Six hundred prisonners [sic] of war had been engaged on work connected with this tunnel and two hundred of them were chosen to escape. ............."

"All the escapers were provided with civilian clothes, forged documents, money, food, maps and compasses. The first thirty who were going by train had attaché cases, but no Red Cross since the discovery of Red Cross food and general maps would give them away. Each of them had an identity card, ration cards, letters from German firms, and an authority to travel by train. About forty others were to travel on workmen's trains for part of the journey. The remainder were to travel on foot. ............"

Report on the ‘Great Escape’ compiled by the escape committee after the war, June 1950. Catalogue reference: AIR 40/285

The aftermath

Of the 76 POWs who made it out during the ‘Great Escape’, only three completed their journeys to freedom. Soon after the escape, 50 escapees, including Bushell, were murdered by the Gestapo. This was a clear violation of the Geneva Convention, which protected the rights of POWs. This response also quickly put a stop to all escape activity from POW camps in Europe, for fear that further reprisals would occur.

At the end of the war, detailed investigations into the events after the escape were undertaken. The surviving perpetrators were tried and convicted, many of whom were executed for their role in the aftermath.

Bushell was cremated soon after his execution and is now buried in the Poznan Old Garrison Cemetery in Poland. He was posthumously Mentioned in Despatches for the leadership he provided as a POW. A memorial to ‘The Fifty’ was built in Sagan (now Zagan), near to the site of Stalag Luft III. You can visit it to this day.

Great Escape memorial at Sagan, Poland, to officers shot while escaping. Catalogue reference: AIR 2/7113

Records featured in this article

-

- From our collection

- AIR 81/507

- Title

- Air Ministry files relating to casualties suffered during operations and accidents

- Date

- 1 January 1940 – 31 December 1953

-

- From our collection

- WO 416/47/197

- Title

- German Record cards of British and Commonwealth Prisoners of War: Roger Bushell

- Date

- 1939–1945

-

- From our collection

- AIR 40/229

- Title

- Photographs of Allied prisoner of war camps in Holland and Germany

- Date

- 1942–1945

-

- From our collection

- AIR 40/285

- Title

- Report on the ‘Great Escape’ compiled by the escape committee after the war

- Date

- 1942–1950

-

- From our collection

- WO 311/169

- Title

- War Crimes Interrogation Unit final report on the Great Escape from Stalag Luft III

- Date

- 1946

-

- From our collection

- AIR 2/7113

- Title

- Memorial at Sagan, Poland, to officers shot whilst escaping from Stalag Luft III

- Date

- 1946–1951

Read more

Image gallery: Escaping Colditz

Explore this image gallery about the infamous castle, used as a Second World War prison camp for Allied officers who had escaped other camps or were deemed a security risk.

Podcast: Second World War Captives

Three historians explore documents – some previously unseen by the public – that describe the experiences of prisoners of war and civilian internees in the conflict.

Blog: The Archivists’ Guide to Film – The Great Escape

Experts at The National Archives look at The Great Escape (1963), directed by John Sturges. Do the film's action, cast and humour outweigh its many historical inaccuracies?