A life in documents

Collections at The National Archives can be used to highlight the lives of famous figures from the medieval period. The higher up the social scale these figures sat, the greater the chances that valuable records survive.

For a king like Richard III (1452–1485), The National Archives holds records that mark key points in his life as an aristocrat, his political career, his brief reign and his later reputation. He remains a controversial but fascinating figure, and the original documents play an important role in establishing the facts upon which historians have based their interpretations.

Becoming Lord of the North, 1452–1483

Richard Plantagenet was born on 2 October at Fotheringhay in Northamptonshire. His father, Richard 3rd duke of York was heir presumptive to King Henry VI’s throne. His mother, Cecily Neville, was a direct descendant of King Edward III. His father failed in his attempts to become named formally as the next king, and as a child Richard endured the risks and dangers linked to York’s increasingly direct challenge for the throne.

When civil war broke out in 1459, Richard watched as his father was killed in battle at the end of 1460 and his brother Edward, picking up their father’s claim, fought his way to become King Edward IV by March 1461.

The kingmaker

As the brother of the king, Richard became duke of Gloucester in October 1461 and a Knight of the Garter a year later. His education was then entrusted to the king’s chief ally, Richard Neville, earl of Warwick – ‘the kingmaker’.

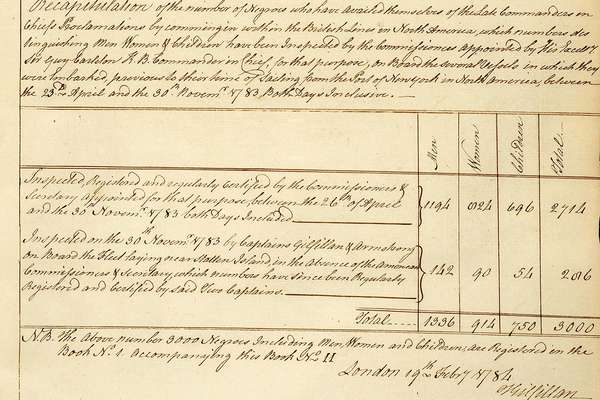

To Richard, earl of Warwick, for costs and expenses incurred by him for the Lord Duke of Gloucester, the King’s brother, and for an exhibition &c, of the wardship and marriage of the son and heir of the Lord de Lovell, £1000.

Exchequer of Receipt. Tellers’ Rolls, Michaelmas 5 Edward IV (1465). Expenses of the earl of Warwick for raising Richard of Gloucester and Francis, Lord Lovell at Middleham. Catalogue reference: E 405/43, m. 2.

Under Warwick’s guardianship, Richard became a familiar figure across the north, from York to Durham and Cumberland. His lifelong friendship with Francis Lovell suggests that their teenage years were enjoyable. Warwick and the king soon fell out over the direction of policy and the king’s marriage.

By 1469, Warwick was a rebel and Duke Richard had been recalled to court. He remained loyal to his brother as civil war erupted again, with Warwick, in alliance with those who remained true to Henry VI, forcing King Edward into exile.

Henry VI was briefly restored, but Edward reclaimed his throne by the spring of 1471, killing Warwick at the Battle of Barnet – probably Richard’s first experience of combat.

Richard was given Warwick’s vast estates across the north, and also looked after the king’s lands in the region. That gave him immense power and a platform from which to become the dominant figure within northern society.

Cementing power

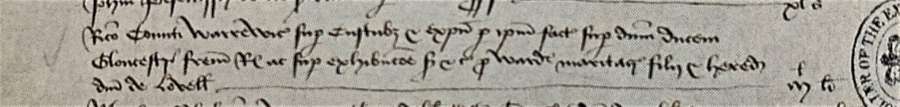

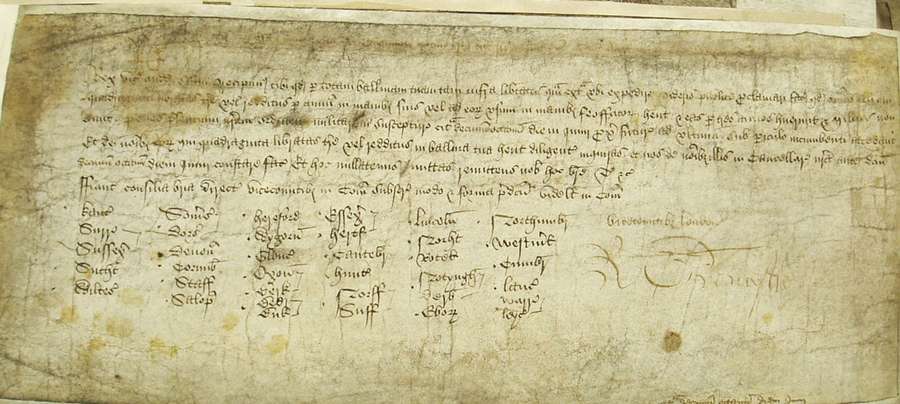

This document shows payments of annuities to Richard's servants in Yorkshire 1473, just after he was granted the earl of Warwick's estates at Middleham. Many of these men continued to serve Richard up to 1485.

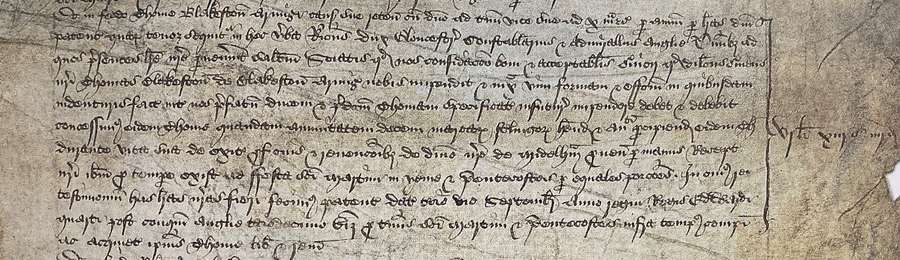

And for the fee of Thomas Blakeston of Blakeston, esquire, by reason of his retainer for term of his life by the lord, at 10 marks per annum by letters patent of the lord, the tenor of which follows in these words: Richard duke of Gloucester, constable and admiral of England to all whom these presents shall come, greeting. Know you that in consideration of the good and acceptable service that our wellbeloved servant Thomas Blakeston of Blakeston, esquire has given and is due to give to us in the future, according to the force, form and effect specified in certain indentures made between us, the aforesaid duke and the said Richard. We have granted to the same Thomas an annuity of ten marks sterling to have and take each year during his life proceeding from the issues, profits, and revenues of our lordship of Middleham by the hands of our receiver there for the time being, at the feasts of St Martin in winter and Pentecost by even portions.

Duchy of Lancaster: Accounts of Auditors, Receivers, Feodaries and Ministers: Warwick and Despenser lands, Ministers’ Accounts for Middleham and Richmondshire, 13 and 14 Edward IV (1473 –1475). Catalogue reference: DL 29/648/10485.

Duchy of Lancaster copyright material in The National Archives is reproduced by permission of the Chancellor and Council of the Duchy of Lancaster

These records show the techniques Richard used to build a loyal following across the north of England. He was able to do this because it was the king’s policy to have his loyal brother in charge of the entire region.

Richard used his marriage to one of the earl of Warwick’s daughters, Anne Neville, in July 1472 to concentrate his estates and power. This step boosted his income and made his leadership more attractive. An agreement with the earl of Northumberland in 1474 ensured his dominance and effectively made other northern lords his servants.

Richard was enthusiastic for war with France in 1475 and led an English invasion of Scotland in 1482. His reward was a grant of a palatinate (an area of devolved crown power, ruled by a lord who held most of the king’s legal and financial rights) in the far northwest England and land he was given licence to conquer in south west Scotland. This step shows how well trusted Richard was by his brother Edward IV and just how powerful he was across the north of England.

From Protector to King, 1483

Loyalty to Edward IV’s heir, however, soon unravelled when the king died unexpectedly on 9 April 1483. Edward, Prince of Wales – now the uncrowned Edward V – was at his castle of Ludlow when he received the news. Richard swore an oath of loyalty and preparations were started for a coronation of the twelve-year-old boy.

As the king’s uncle, Richard secured a position at the head of government in Edward’s name. But he soon acted with his allies to purge the power of Queen Elizabeth’s family and to arrest those who had a strong interest in seeing Edward crowned quickly. The coronation was postponed and there were delays in proving Edward IV’s will. Richard was possibly investigating the illegitimacy of the dead king and his children.

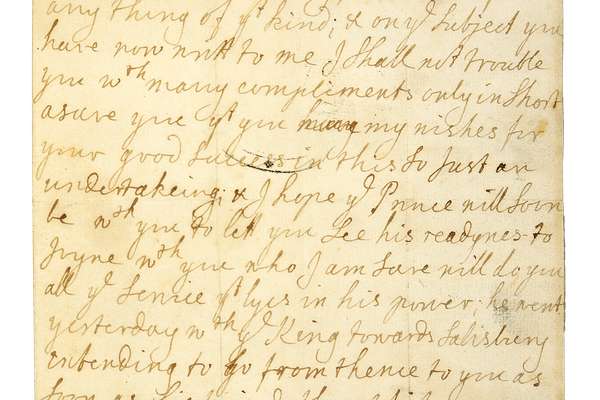

Factionalism resurfaced. Yet even on 9 June a surviving letter of London news sent to a knight in Oxfordshire (catalogue reference: SC 1/46/206) shows concern at events but little panic and confidence that although the queen had fled to sanctuary, the young king’s coronation was still expected and government business was ongoing under the protectorship of Richard, duke of Gloucester.

Edward V’s abbreviated signature (top left) and Richard Gloucester’s signature (bottom left) on a warrant commanding sheriffs to organise the election of MPs for a parliament on 25 June 1483. Catalogue reference: C 81/1529.

Trouble and doubt

On 10 June Richard ordered troops from the north and within days assembled meetings of the royal council with the intention of removing other opponents. Lord Hastings, suspecting nothing, was summarily beheaded on the green at the Tower of London on 13 June.

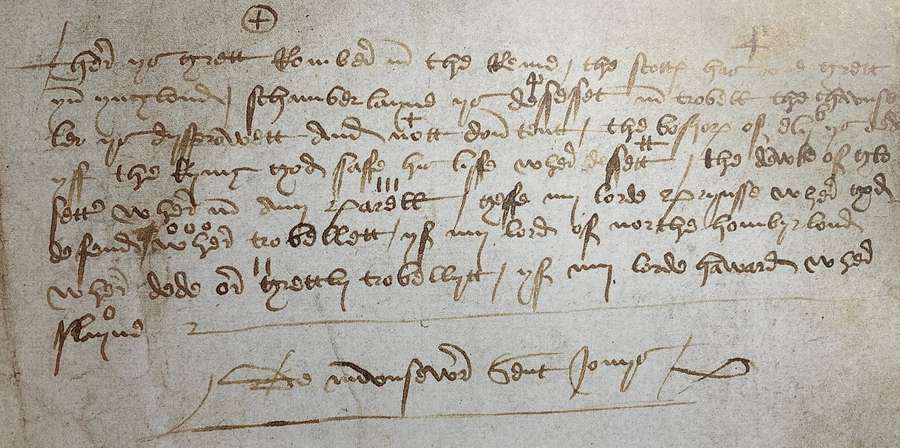

A second surviving letter to the same Oxfordshire knight, Sir William Stoner, is full of urgent news and concern for the way things had turned; reporting ‘much trouble and doubt’ (catalogue reference: SC 1/46/207).

Another rumour-filled note from around this time, among the papers of the merchant George Cely, shows just how confusing the situation in London had become.

There is great rumour in the realm. The Scots have done great in England. The Chamberlain is deceased in trouble the Chancellor is disproved and not content. The bishop of Ely is dead. If the king, God save his life, were deceased. The duke of Gloucester were in any peril. If my lord Prince were, God defend, were troubled. If my lord Northumberland were dead or greatly troubled. If my lord Howard were slayne

Ancient Correspondence of the Chancery and Exchequer. John Weston, master of the knights of St John of Rhodes, June 1483. Catalogue reference: C 81/1529.

Richard’s reign, 1483–1485

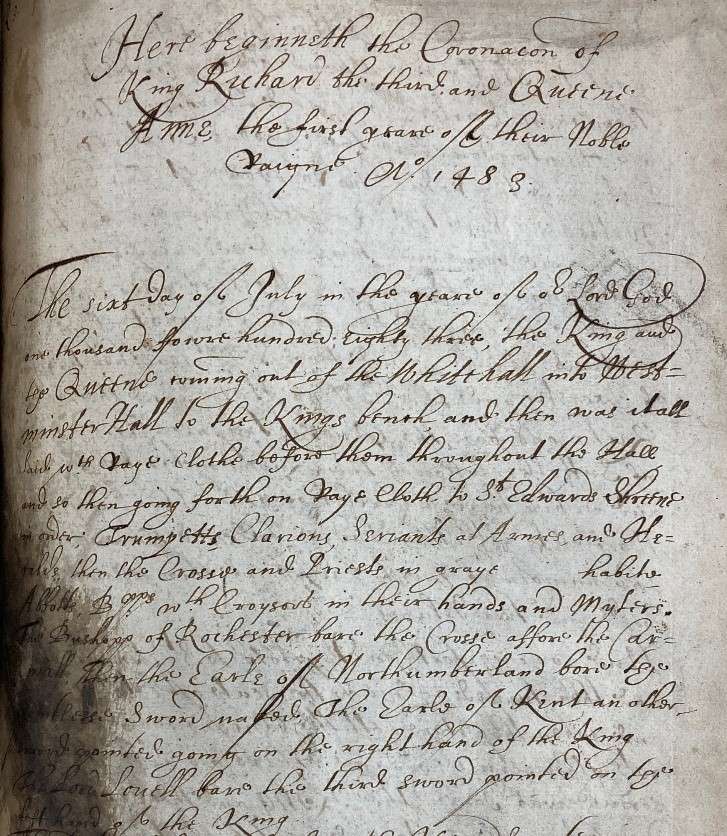

How did Richard express his own power as king, and how do the records offer us some insights to his thinking? In common with other medieval monarchs, Richard evidently felt that he had been chosen by God to rule. The records of the ceremonial of his and Queen Anne’s coronation at Westminster Abbey on 6 July 1483 underline this idea of divine endorsement for England’s monarchs.

A 17th-century copy of the ‘Little Device’ recording the form and process of the coronation ceremony. Headed, ‘Here beginneth the Coronacon of King Richard the third and Queene Anne, the first yeare of their noble raigne Ao 1483’. Catalogue reference: SP 8/9, fol. 91v.

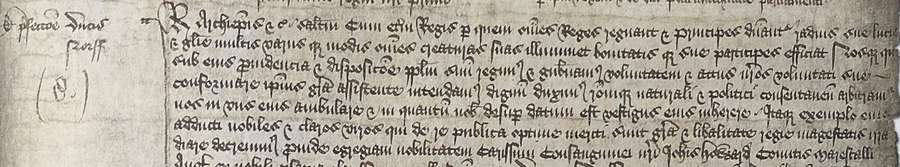

This belief also appeared in Richard’s justification for rewarding his friends. When, on 28 June 1483, he promoted his friend John Howard to be duke of Norfolk, Richard included words that show how he felt about the closeness of the king to God.

The king to the archbishops etc, Greetings. Whereas the radiance of the eternal king through whom all kings reign and princes have dominion, the ray of His light and glory, in many and divers ways shines upon all His creatures and marks out those who share in His goodness, and whereas We, who under his providential design rule and govern His people, endeavour by His grace to conform our will and acts to His will, we have deemed it right [and] consider it fit by natural and prudent reason to walk in His ways and, insofar as it is granted to us from above, to mark His footsteps, therefore, led by His example, we have determined by the grace and liberality of our royal majesty to illumine those noble and distinguished men who are most deserving of the public weal, and hence we have determined to raise the outstanding nobility of our most dear cousin John Howard ....to the higher degree of honour [etc]

Grant of the title of duke of Norfolk to John, Lord Howard, 28 June 1483 (catalogue reference: C 53/198, m. 1.)

No depictions of Richard's coronation are known to exist, but this illustration from 1509 of a Tudor ceremony featuring two angels demonstrates how the coronation of a medieval monarch was seen as a solemn expression of divine favour. Catalogue reference: E 405/185.

The only candidate for the throne

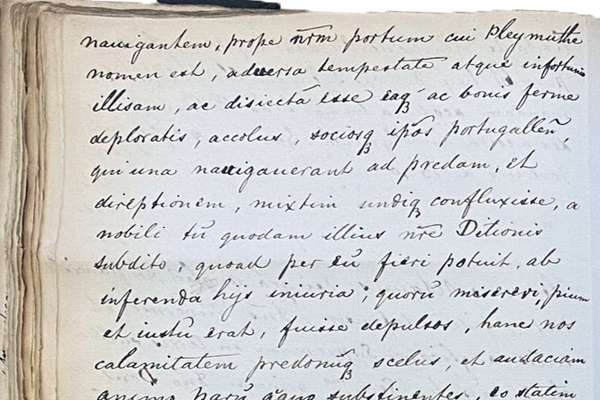

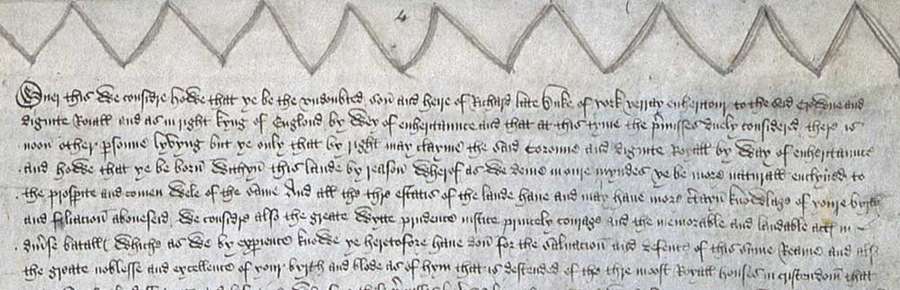

More broadly, God’s support underpinned how Richard’s accession was explained. But it also incorporated a sense of his right and fitness to rule. In his parliament of January 1484, Richard’s claim to the throne was presented in the form of a petition from the Commons of England.

Richard was effectively asked to become king to save the country from the problems that had arisen during Edward IV’s reign – the king’s scandalous living, the illegitimacy of all his children, the overbearing power of the queen’s family, and the disbarment of other possible heirs from within the royal family.

Richard certainly controlled the tone and content of this document and as such it represents his personal thinking and justification for taking the crown. Richard’s own skills and virtues were championed in terms that built a case for him to be the only realistic candidate for the throne.

Moreover, we consider how you are the undoubted son and heir of Richard, late duke of York, the true inheritor of the said crown and royal dignity, and by right king of England by way of inheritance, and that at this time, the things stated duly considered, there is no other person living, except you, who by right may claim the said crown and royal dignity by way of inheritance; and how you were born within this land, by reason of which we judge that you are more naturally inclined towards its prosperity and common weal, and all the three estates of the land have, and may have, more certain knowledge of your aforesaid birth and parentage. We also consider the great wit, prudence, justice, princely courage and the and laudable acts in various battles which we know by experience that you have previously displayed for the salvation and defence of this same realm, and also the great nobility and excellence of your birth and blood, as one who is descended from the three most royal houses in Christendom, that is to say, of England, France and Spain.

Parliament Rolls, 1 Richard III. Catalogue reference: C 65/114, m. 4.

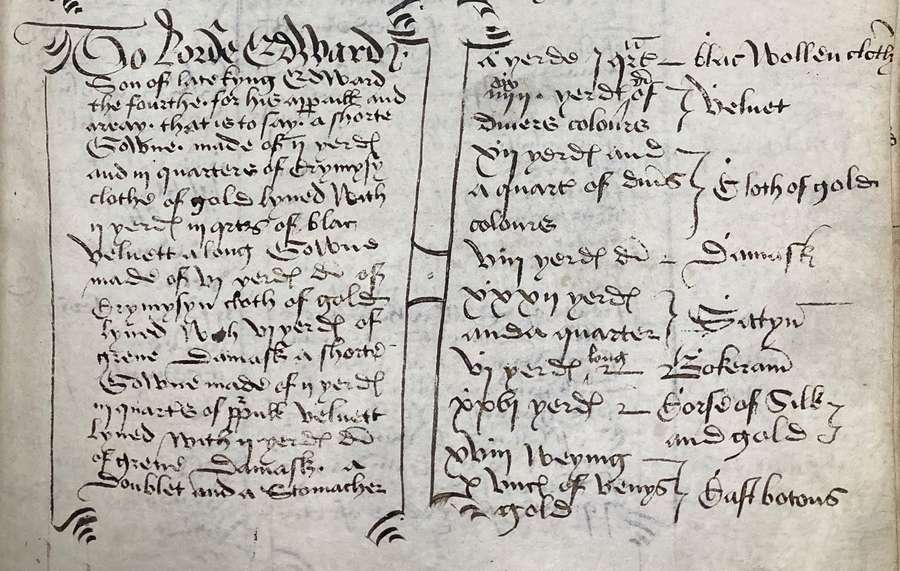

The process of crushing the claims of rivals was seen in the treatment of Edward V’s status. In the preparations for Richard’s coronation at the end of June, he was still referred to as the Lord Edward and given expensive clothing and a body of guards for the day of the coronation.

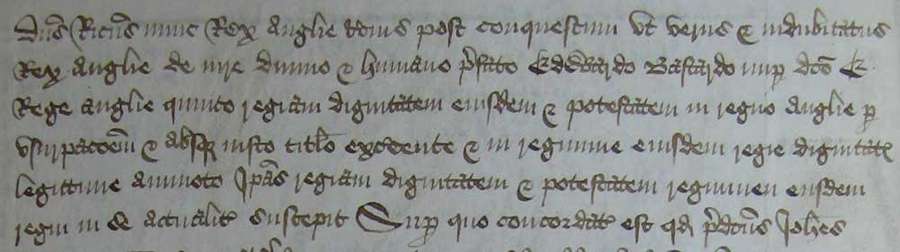

Gowns and cloth provided for ‘Lorde Edward, son of late kyng Edward the fourthe for his apparaill and array’ at his Uncle Richard’s coronation. Catalogue reference: LC 9/50, fol. 109r.

Soon after, the language of illegitimacy was used when Edward was mentioned in official records – indicating that the civil servants at least, were expected to reflect the official message that Edward IV’s children had not been born to a lawful marriage and therefore had no rights as rulers. In this document, Richard is referred to by Exchequer officers as ‘a true and undoubted king of England’, while Edward is reduced to the status of ‘Edward the Bastard, late the said Edward king of England the fifth’, who had no right to be king.

‘Edward the Bastard’ on the Exchequer: King’s Remembrancer: Memoranda Roll. Additions early in 1484 to an entry from Edward V’s brief reign in April–June 1483. Catalogue reference: E 159/260, recorda rot. 6.

Resistance and rebellion

Despite basing his claim to the throne on his family lineage and legitimacy, Richard’s actions in displacing Edward V generated resistance from within the previously cohesive group that had ruled England for the previous 20 years.

During his first progress around the country as king (which included elevating his own son, Edward, to be Prince of Wales, at York Minster on 5 September), Richard learned of a plot to break Edward V and his brother, Richard, from their imprisonment in the Tower of London.

At some point in September, the Duke of Buckingham decided to rebel. He had been Richard’s right-hand-man in the manoeuvres to take the throne. A broader uprising soon developed across the whole of southern England. This was also the first time that Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond – in exile since 1471 – was mentioned as a candidate for the throne in rivalry to Richard.

Richard faced a rebellion by many of Edward IV’s old followers who had expected the ruling elites to support a smooth transition to Edward V’s rule.

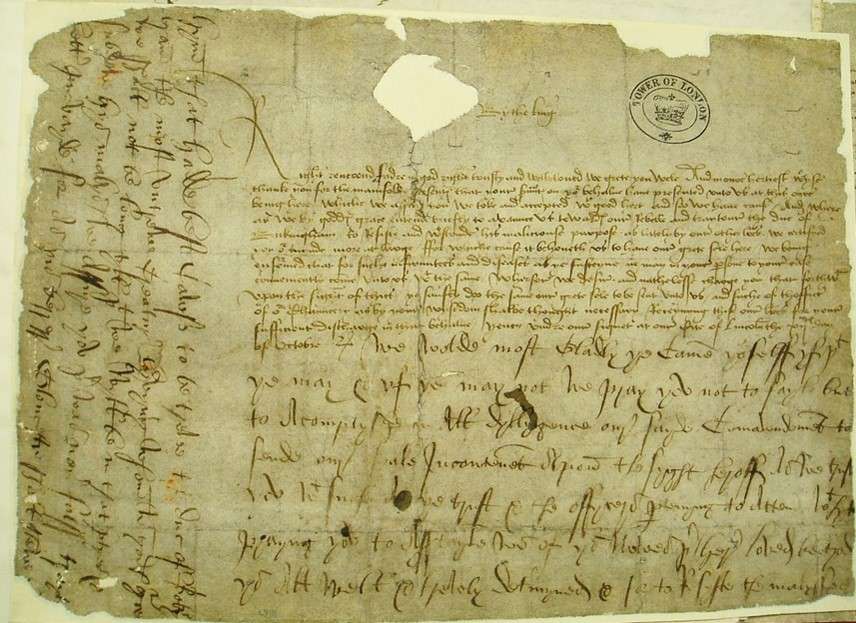

Away from London, Richard was concerned about the level of control of government. From Lincoln on 12 October 1483, he added an unusual personal rant about the treason of Buckingham to a request that the Great Seal of England should be sent to him by his Lord Chancellor, John Russell, Bishop of Lincoln.

We would most gladly you came yourself if that you may & if you may not we pray you not to fail but to accomplish in all diligence our said commandment to send our seal incontinent upon the sight hereof as we trust you with such as you trust & the officers pertaining to attend with it praying you to ascertain us of your news. Here, loved be god, is all well & truly determined & for to resist the malice of him that had best cause to be true the Duke of Bokynhame the most untrue creature living whom with god’s grace we shall not be long till that we will be in that parties & subdue his malice. We assure you that was never false traitor better provided for as this bearer Gloucester shall show.

Chancery: Warrants for the Great Seal, Series 1, warrants under the signet, 1-2 Ric III. 12 October 1483. Catalogue reference: C 81/1392/6.

Once this rebellion had been broken by a combination of bad weather and a failure to coordinate among the rebels, the basis for Richard’s reign became the measures agreed at the parliament of January 1484. Many enemies were attainted, with their lands and goods forfeit to the Crown.

Richard was able to oversee a few parliamentary measures on the economy and the law, notably tightening procedures for raising income from his estates and outlawing the forced cash gifts or benevolences that had been a cause for complaint in Edward IV’s reign.

He initiated a Council of the North to build stronger government for the region he knew so well, and appointed officers at Westminster to hear the complaints of poor people (an early form of the Court of Requests).

Henry Tudor

It soon became clear, however, that Richard’s kingship could not progress until his rival, Henry Tudor, had been captured or eliminated. Henry’s exiled supporters in Brittany had accepted the fleeing English rebels in autumn 1483, and with their experience behind his slim cause, he soon began to plan another attempt to unseat King Richard.

Richard’s proclamations tried to undermine the pro-Tudor plot. He took measures against suspects still in England, and the stakes were raised when the deaths of Edward, Prince of Wales and Queen Anne by March 1485 robbed Richard of the security of his family.

He also had to deal with the disruption caused by the ambitious conspiracy against him, and from the early summer of 1485 he moved his court to Nottingham to prepare for the expected landfall of Henry Tudor and his mercenaries from France.

Bosworth

The small invading army arrived near Milford Haven in West Wales on 7 August. Richard’s large force moved to Leicester, but as Tudor marched up the Welsh coast and across to enter England near Shrewsbury, defections from the king began to boost Tudor’s morale.

When the armies met at Bosworth on 22 August, Richard still had the superior numbers. Delays from the Stanley family and inability of the king’s northern followers to engage as they had expected, under the Earl of Northumberland’s command, meant that after hours of fighting a stalemate between the armies came about.

Richard then launched a rapid cavalry charge across the battlefield, directly at Henry Tudor’s banners. A desperate defence only just kept the invader from death, and it was Richard who was soon overwhelmed and killed, when Sir William Stanley’s forces entered the fight on Tudor’s side.

Our knowledge of the course of this decisive battle comes mainly from narrative sources, which The National Archives does not possess.

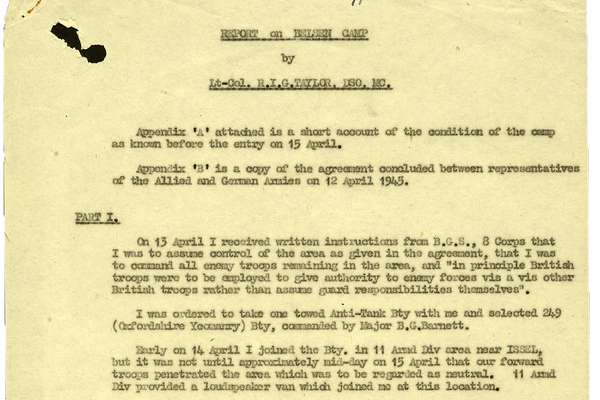

Records here show the consequences of the fighting – in compensation for damage to ready-to-harvest crops and in the human cost of war, with the dedication to the dead of the battle in a new chapel at the village of Dadlington.

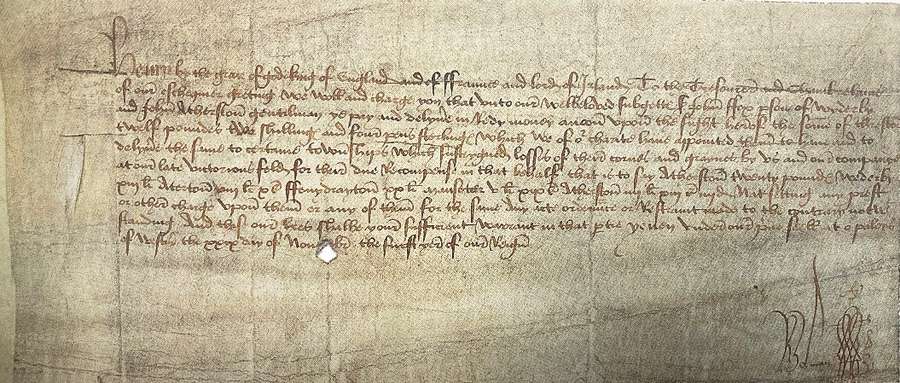

On 29 November 1485, Henry Tudor, now Henry VII, compensates the parishes whose crops were destroyed by the marching and fighting at Bosworth. Catalogue reference: E 404/79/340.

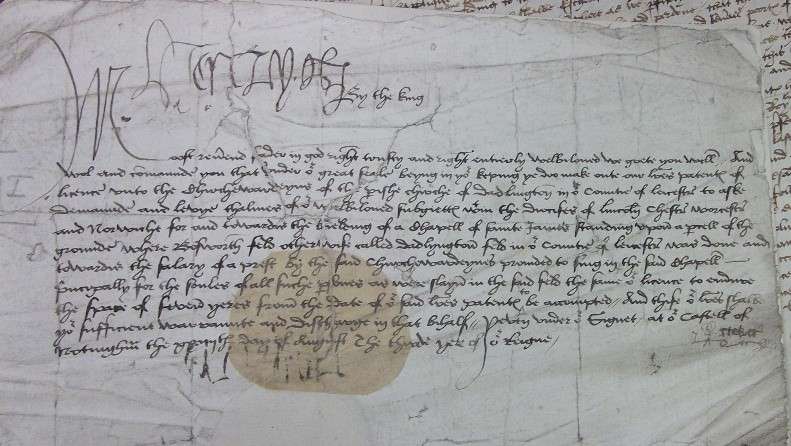

On 24 August 1511, Henry Tudor's son, Henry VIII, licenced the building of a chapel at Dadlington on the ground where Bosworth was fought, and with a salary for a priest to sing masses for the dead. Catalogue reference: C 82/367, no. 24.

The battle is referenced in many documents by those who were there, often as proof of long term support for the victorious Henry Tudor, who took the crown as Henry VII.

Legacy

The humiliation and public display of Richard III’s body at Leicester and his burial in the Greyfriars monastery there might have been the end of his story. But a dispute over the costs of his first tomb, and the subsequent discovery and reburial of his body in 2014, reveal that there was and is great interest in Richard’s afterlife in local society and national culture.

During the intervening years, Richard was portrayed as a villain by writers like Thomas More and William Shakespeare, and the reputation of this complex and fascinating king has become simplified and polarised.

His story contains both shocking political actions and examples of kindness and great leadership, but on the key issues, such as the true fate of the Princes in the Tower, we await the discovery of crucial new evidence.

The sources from The National Archives explored here show how it is possible to reassemble the evidence for medieval lives – certainly of people from the ruling elite – from within the archives of government business, the law and even the private papers that these Crown responsibilities sometimes swept up.