Record revealed

Report on the liberation of Bergen-Belsen

On 15 April 1945, during the final months of the Second World War, the British army liberated the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. This report provides an eyewitness account of the liberation and of the horrors they found.

Important information

This page highlights an eyewitness account of the Holocaust that includes shocking and graphic descriptions of human suffering.

Images

Image 1 of 5

Partial transcript

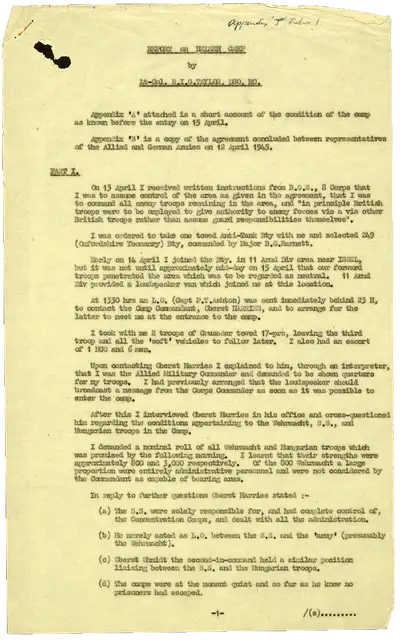

REPORT ON BELSEN CAMP

By

Lt-Col. R.I.G. Taylor, DSO, MC.

On 13 April I received written instructions from B.G.S., 8 Corps that I was to assume control of the area as given in the agreement, that I was to command all enemy troops remaining in the area, and “in principle British troops were to be employed to give authority to enemy forces vis a vis other British troops rather than assume guard responsibilities themselves”.

At 1330 hrs an L.O. (Capt P.T. Ashton) was sent immediately behind 23 H, to contact the Camp Commandant, Oberst HARRIES, and to arrange for the latter to meet me at the entrance to the camp.

Upon contacting Oberst Harries I explained to him, through an interpreter, that I was the Allied Military Commander and demanded to be shown quarters for my troops. I had previously arranged that the loudspeaker should broadcast a message from the Corps Commander as soon as it was possible to enter the camp.

After this I interviewed Oberst Harries in his office and cross-questioned him regarding the conditions appertaining to the Wehrmacht, S.S., and Hungarian troops in the Camp.

I demanded a nominal roll of all Wehrmacht and Hungarian troops which was promised by the following morning. I learnt that their strengths were approximately 800 and 3,000 respectively. Of the 800 Wehrmacht a large proportion were entirely administrative personnel and were not considered by the Commandant as capable of bearing arms.

Image 2 of 5

Partial transcript

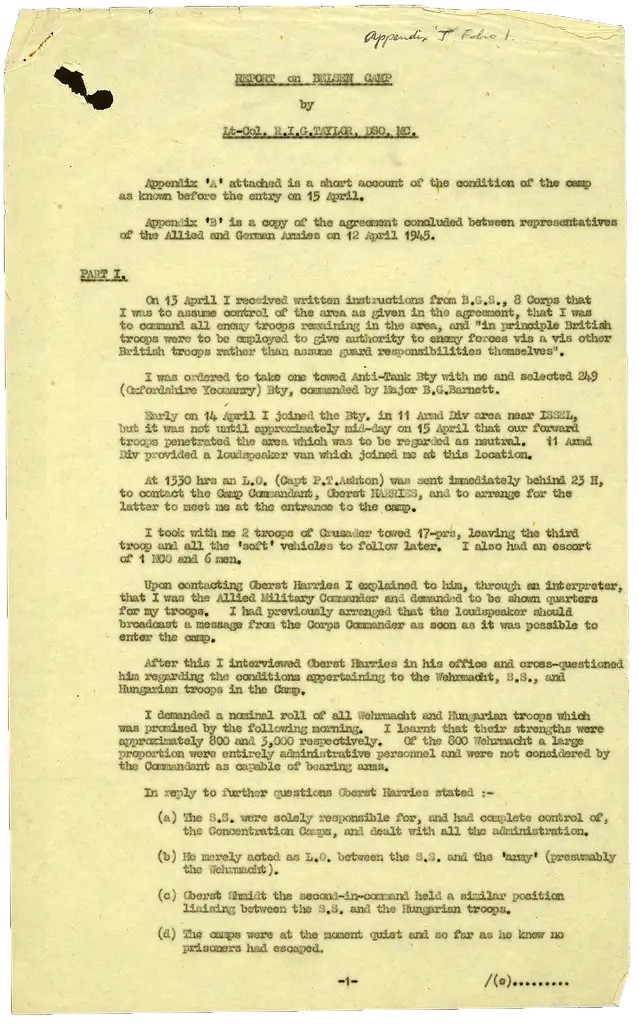

I, together with Major Barnett and Oberst Harries and the escort proceeded immediately to Camp 1, where I met the S.S. leader, KRAMER. He stated that his men were armed, and that if they were disarmed they could not administer the camp, as they would be overpowered by the internees. In view of the fact that there was no alternative form of administration available I agreed that they should temporarily retain their arms. He stated that his men worked in the cookhouses, and did all the administration in the camp.

The S.S. leader was then ordered to accompany myself, Major Barnett, the interpreter and escort to his office.

In answer to questions he stated:-

a. All papers with regard to the prisoners had been destroyed on orders from Berlin, having previously stated that 2,000 papers were available. When asked why he said this he stated he did not know the order had been carried out.

b. There were approximately 40,000 men and women in the camp, a large proportion of whom had only recently arrived from another camp that had been over-run.

c. There was enough food in the camp to feed the prisoners for 3 days.

d. So far as he knew no prisoners had escaped.

e. There were approximately 25 S.S. personnel administering the camp. A nominal roll was asked for and when this was produced it showed 50 names. No physical check was made of S.S. personnel.

An occasional shot was being fired from inside the camp, and on passing through the gates we saw the camp and the internees for the first time.

Image 3 of 5

Partial transcript

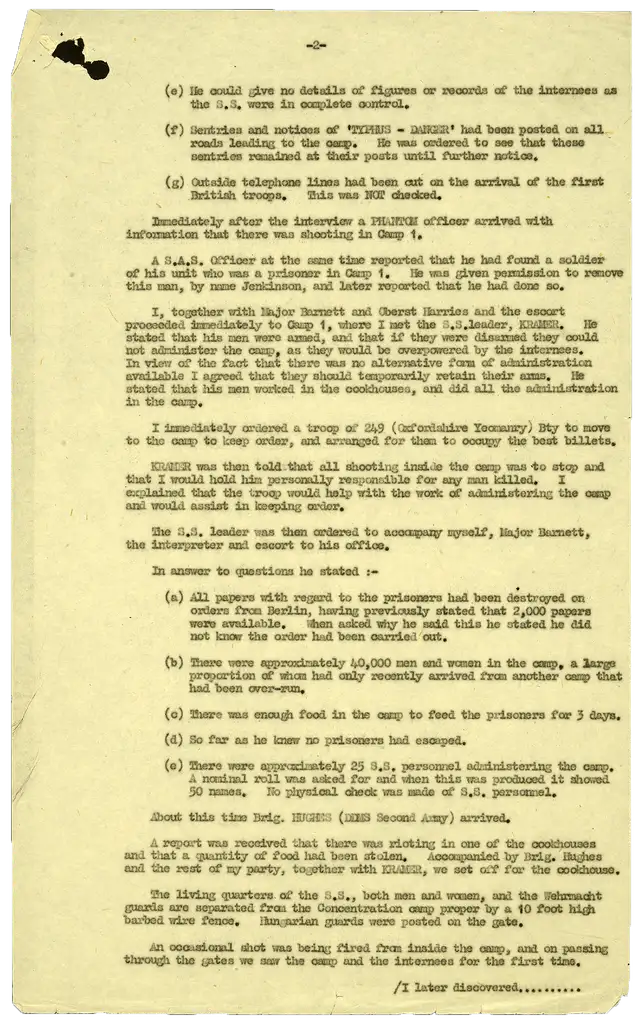

I later discovered that the camp was divided into 6 blocks. Each block being separated from the other by barbed wire. There were 4 women’s blocks, 2 mens – there being 5 cookhouses in all.

Inside these wire cages were approximately 100 huts, some with bunks and some without. It was quite impossible for all the internees to enter the hut allotted to them at the same time, a large proportion were therefore living in the open.

As we walked down the main roadway of the camp we were cheered by the internees, and for the first time we saw their condition.

A great number of them were little more than living skeletons, with haggard yellowish faces. Most of the men wore a striped pyjama type of clothing – other wore rags, while the women wore striped flannel gowns, or any other garment that they had managed to acquire. Many of them were without shoes and wore only socks and stockings.

There were men and women lying in heaps on both sides of the track. Others were walking slowly and aimlessly about – a vacant expression on their starved faces.

Still the occasional shot was ringing out as we made our way further down the camp towards the potato patch. This consisted of a few rows of potatoes covered by earth, and on it were lying 6 or 7 corpses which had obviously just been shot. There were other living skeletons that had been wounded, and who were crying out with pain. No attempt was being made to relieve their distress, although S.S. troops were in the vicinity.

Image 4 of 5

Partial transcript

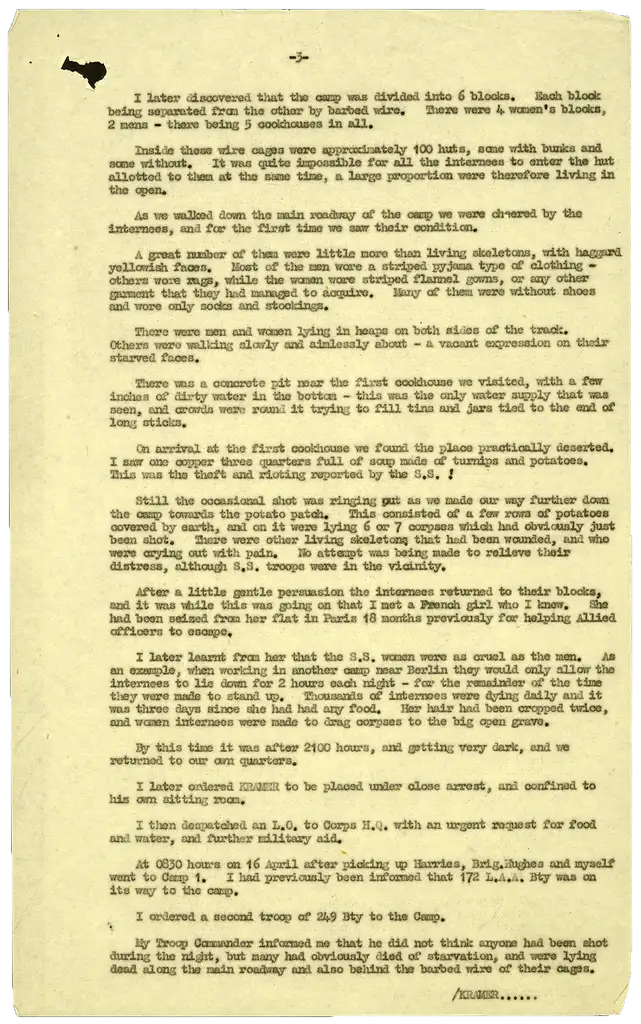

There was no sanitation of any sort in the camp, not even trenches for use as latrines.

Lt-Col. Michie (A.D.H. 8 Corps) later reported that he had seen figures indicating that 17,000 bodies had been cremated during March.

We then drove through the womens camp and saw 2 large piles of naked corpses and the uncovered put some distance further on.

There were heaps of dead in every cage and it was quite obvious that unless food and water arrived soon the whole camp would starve to death.

A message was broadcast telling the internees that food and water were on the way, the German rule in the camp was over and that we were doing everything in our power to relieve their misery.

Here conditions were very much better, the internees living in stone barracks, guarded by Hungarians, but it was quite obvious at a glance that the majority were starved almost beyond recognition.

The rest of the day was spent trying to procure, and then issue, food and water to Camp 1. This was eventually achieved and I am certain that most of those capable of walking received something to eat. There was no attempt to rush the food lorries or water carts when they arrived, and it was quite obvious that in spite of their appalling condition the internees were doing all in their power to help us.

So far as I had been able to see the S.S. made no material difference to the administration of the camp so I determined to arrest them forthwith.

Image 5 of 5

Partial transcript

On 17 April the remaining S.S. were arrested in Camp 1, 28 men and 25 women being taken. KRAMER’s deputy was missing from the parade, but was later picked up in the camp disguised as an internee. The whole lot were locked in the cells, just outside the concentration camp proper, much to the delight of the inmates.

The men were later set to work carting corpses from the camp to the big pit – the women joined them later helping with this job. They were given the same ration as the internees had had prior to our entry. During the first night one committed suicide and 2 more attempted but failed to do so. The following day two tried to run away but were immediately shot.

KRAMER after being questioned several times by the F.S.P. was removed by them to CELLE P.O.W. camp on 18 April.

A British internee from the Channel islands who was released stated that he had seen cannibalism in the camp, and Major Barnett saw a corpse which had had several fleshy parts removed.

The death rate in the camp hospitals on the night 16/17th was reported as approximately 500, and I do not think it an exaggeration to estimate the total deaths during each 24 hours as between 500 and 1000.

Why this record matters

- Date

- April 1945

- Catalogue reference

- WO 171/4773

The Bergen-Belsen concentration camp was liberated by Allied forces on 15 April 1945. Located in northern Germany, it had been used as a concentration camp since 1943, primarily housing Jewish prisoners (including Anne Frank and her sister, Margot) but also many Czechs, Poles, resistance fighters, and Allied prisoners of war. It is estimated that by the time of the Allied arrival, nearly 70,000 men and women were being held there, many of whom were dying from disease or were on the brink of starvation.

This report was written by Lieutenant-Colonel Richard Taylor, the Commanding Officer of the 63rd Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Artillery, the first unit to assume responsibility for the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

In the report, Taylor describes what he and his fellow soldiers witnessed in the first few days after the camp’s liberation. It also outlines what actions were carried out to care for the liberated prisoners, and how the Nazi guards of the camp were interviewed and managed.

He describes Camp 1 as consisting of six blocks (four women’s blocks and two men’s), each separated by barbed wire. In each of these 'cages' were 100 overcrowded huts, some with beds, others without, and a large proportion of people living in the open. Camp 2 was described as in better condition, but that most internees here were starved almost beyond recognition.

When first walking down the main roadway, he reports being cheered by the internees, and for the first time, he and his men saw their condition:

'A great number of them were little more than living skeletons, with haggard yellowish faces. Most of the men wore a striped pyjama type of clothing – others wore rags, while the women wore striped flannel gowns, or any other garment that they had managed to acquire. Many of them were without shoes and wore only socks and stockings.

There were men and women lying in heaps on both sides of the track. Others were walking slowly and aimlessly about – a vacant expression on their starved faces'.

Taylor went on to explain how his regiment went about the process of disarming and detaining the guards and taking over the administration of the camp. Their priority was to obtain food and water for the prisoners, many of whom were on the brink of starvation, and to provide medical treatment for those in need. It was quickly found that diseases such as typhoid and dysentery were rife, and preparations were made for the burial of the dead, partly to try and reduce the spread of these diseases. Despite their best efforts, in the months after liberation, a further nearly 14,000 prisoners at the camp died.

The Allied authorities acted quickly to begin the prosecution of those responsible for the suffering at the camp, alongside actions against many of those responsible for the Holocaust across Europe. The trials of 45 of those involved at Belsen and other camps took place from September to November 1945. Eleven, including the Commandant of the camp, Josef Kramer, were sentenced to death by hanging, and a further 20 were imprisoned for various terms.

Following the liberation, survivors were housed at the Bergen-Belsen displaced persons camp around 2 km away. This was managed by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). The last former inmate of Belsen did not leave until September 1950.

Featured articles

The story of

Britain’s youngest prisoner of war: John Giles Hipkin

14-year-old cabin boy John Giles Hipkin became Britain's youngest Second World War prisoner of war in 1941 after he was captured at sea.