Important information

This article references homophobic attitudes and attempts to repress elements of LGBTQ+ lives. 'LGBTQ+' and 'queer' are used here as umbrella terms to reference lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people.

The Local Government Act, 1988

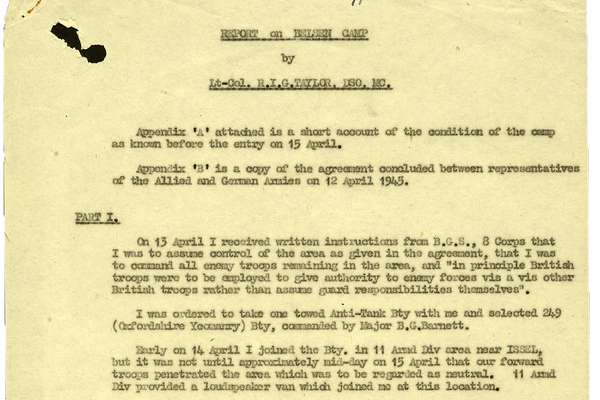

On 24 March 1988 the Local Government Act became law. It contained a number of changes for local authorities from housing to dog licences. But one small part – adding Section 2A to the Local Government Act 1986 – is now infamously known as Section 28. It stated:

(1) The following section shall be inserted after section 2 of the [1986 c. 10.] Local Government Act 1986 (prohibition of political publicity)—

Prohibition on promoting homosexuality by teaching or by publishing material

(1) A local authority shall not—

(a) intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality;

(b) promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship.

Section 28 of the Local Government Act (1988)

The Organisation for Lesbian and Gay Action (OLGA), which was founded specifically to fight the clause, described this as 'the most repressive legislation, since male homosexuality was originally criminalised' (catalogue reference: JA 235/96).

Significant progress in LGBTQ+ rights had been made in previous decades. In fact, the wording of the Act may seem more reminiscent of the early 20th century than the 1980s. Why did the public and political tide turn?

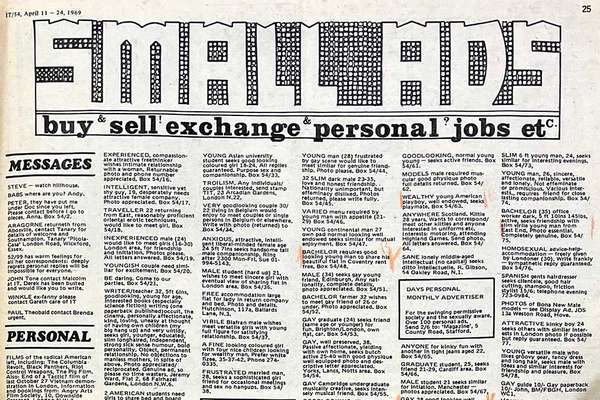

Glad to Be Gay

In 1967 sex acts between men had finally been partially decriminalised in England and Wales. There was a shift in political consciousness, to what cultural historian Matt Cook has called ‘assertive gay pride’. Activism was increasingly about embracing difference, not just about fitting in. The first gay pride parade happened in the UK in 1972 and songs like Glad to be Gay by Tom Robinson were in the charts.

Stateside, the 1969 Stonewall riots showed that LGBTQ+ people would no longer tolerate harassment and persecution. Socially there was more queer visibility – gay characters were introduced to TV shows, pubs and clubs openly cultivated queer visitors, and cultural icons talked more openly about their sexuality and presented in gender fluid ways.

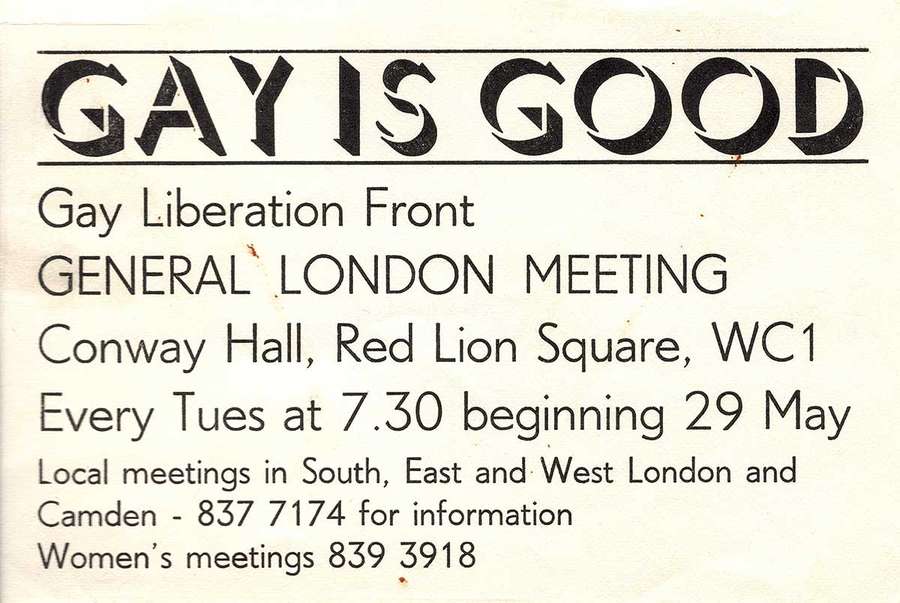

Ticket for Gay Liberation Front meeting, 1973. HCA GLF 2, LSE Library.

Government records show some of the key concerns of lesbian and gay rights organisations at the time, including the continued policing of consenting sex acts between men, unjust targeting of queer venues, the unequal age of consent, attacks on queer people, and the continued criminalisation of homosexuality in the armed forces (catalogue reference: PREM 19/4734)

This was also the era of the AIDS crisis, queer people were rapidly dying or losing friends and lovers. AIDS was often described in the press as the ‘gay plague’.

As activist Dan Glass commented, for these reasons this was a time that 'society desperately needed mass consciousness raising', not the silencing of queer voices.

Transgressive literature

This increased visibility also bled into books and literature. Gay publishers were formed and produced books representing a full range of queer lived experiences.

In 1982 a Playbook for Kids About Sex was published in Britain. The book encouraged young people to ask questions of their sexuality and to form their own opinions about their bodies. The pages included drawings of naked people and mentioned different types of sexual identity.

Front cover of The Playbook for Kids About Sex by Joani Blank and Marcia Quackenbush (catalogue reference: DPP 2/8175).

In 1983, prompted by complaints from evangelical conservative campaigner Mary Whitehouse, the Department of Public Prosecutions (DPP) considered prosecution of the publishers, Sheba Feminist Press, under the Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act 1955 and Obscene Publications Act 1959. A medical advisor felt the text was 'inappropriate' and would not recommend it but concluded it would not 'corrupt or deprave' (catalogue reference: DPP 2/8175).

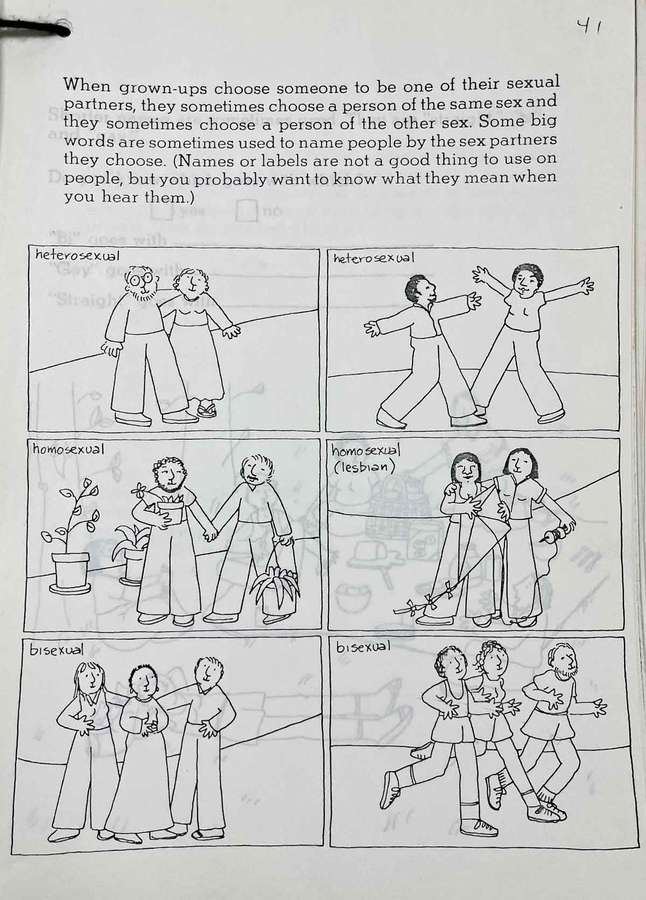

When grown-ups chose someone to be one of their sexual partners, they sometimes choose a person of the same sex and they sometimes choose a person of the other sex. Some big words are sometimes used to name people by the sex partners they choose. (Names or labels are not a good thing to use on people, but you probably want to know what they mean when you hear them.)

An internal page from the Playbook for Kids About Sex by Joani Blank and Marcia Quackenbush (catalogue reference: DPP 2/8175).

Letters sent into the DPP show a range of views on the playbook. A letter from a woman representing Oxford Women Against Violence Against Women wrote:

It makes me furious to find people putting so much time and energy into adverse publicity against this long-awaited book when they continue to ignore the heaps of vile woman-hating and child-abusing pornography.

Catalogue reference: DPP 2/8175

While another letter complained:

as a mother and now a grandmother my heart feels, for the unnecessary burdens put on young children to-day. Please I beg of you do not allow such a book to be published.

Catalogue reference: DPP 2/8175

The press fed into the backlash, claiming the book was aimed at 7-year-olds and describing the text inaccurately as a 'sex manual'.

The DPP was unable to do anything under the existing legislation. The case was dismissed, but this added fuel to the flames.

Another book was soon to catch the eye of conservative campaigners. Jenni Lives with Eric and Martin by Danish author Susanne Bösche – a children’s picture book reflecting a very average domestic home life. The controversy: Jenny lived with her father and his male partner. Such literature was seen 'to promote homosexuality as a normal and acceptable way of life' (catalogue reference: PREM 19/4734). This book not only displayed a gay couple but questioned the nature of a conventional, nuclear family.

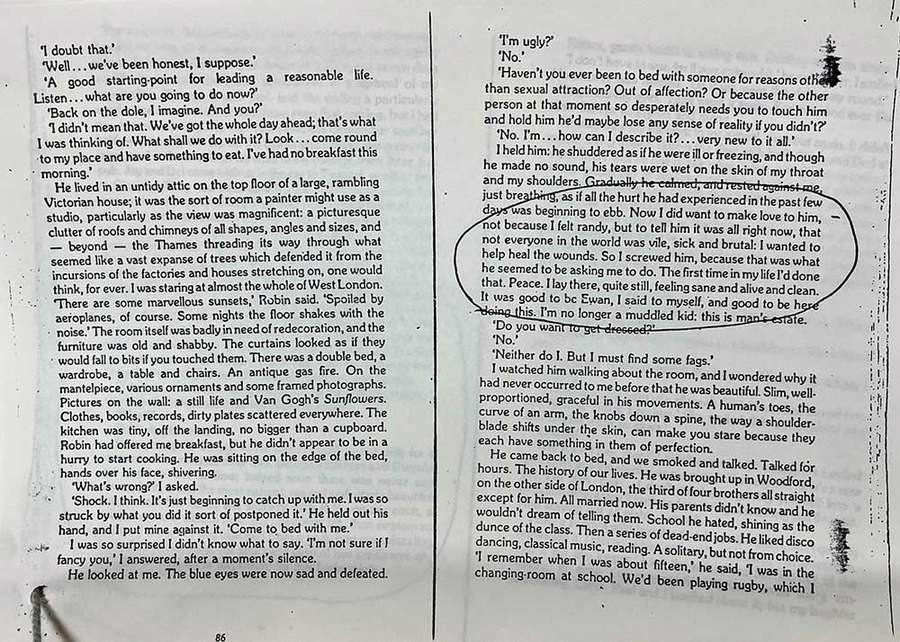

By 1986, the introduction of legislation to address this transgressive literature was being considered. In 1987 Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was briefed on the topic and 1982’s The Milkman is on his Way by David Rees was used to demonstrate the need for stronger legislation. Excerpts were provided to Thatcher 'in order to obtain the flavour of this very disturbing book'.

The book depicted a range of relationships between the protagonist, Ewan, and other men over his teenage years. The unequal age of consent for homosexual acts at the time meant some of the relationships depicted were illegal. The content was sexually explicit but also depicted a very relatable sense of self-discovery. One sexual encounter between men in the book is described by the protagonist as 'the most natural, normal and utterly beautiful experience'.

I held him: he shuddered as if he were ill or freezing, and though he made no sound, his tears were wet on the skin of my throat and my shoulders. Gradually he calmed, and rested against me, just breathing, as if all the hurt he had experienced in the past few days was beginning to ebb. Now I did want to make love to him, not because I felt randy, but to tell him it was all right now, that not everyone in the world was vile, sick and brutal: I wanted to help heal the wounds. So I screwed him, because that was what he seemed to be asking me to do. The first time in my life I’d done that. Peace. I lay there, quite still, feeling sane and alive and clean. It was good to be Ewan, I said to myself, and good to be here doing this. I’m no longer a muddled kid: this is man’s estate.

Highlighted extracts of The Milkman is on his Way by David Rees, shared in a briefing to Margaret Thatcher (catalogue reference: PREM 19/4734).

An annotation on the photocopies claims the book was obtained from the children section of Haringey library by 15-year-old girl (catalogue reference: PREM 19/4734).

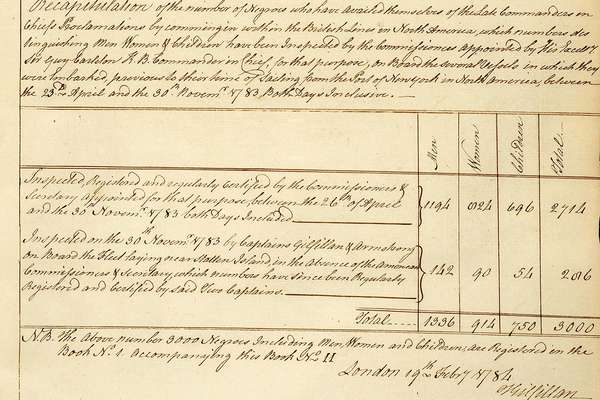

Public funding

One of the concerns about these books was that local authorities were enabling access to them and using public funds to do so. Queer literature and young audiences were stuck in the middle of a much wider battle over local authority autonomy and central government control.

Some Labour-dominated councils were increasingly advocating for LGBTQ+ rights – funding community initiatives and supporting access to positive literature. Schools sat under the local educational authorities, and at that time no formal national curriculum existed, which gave a considerable amount of freedom.

Certain high-profile cases about school autonomy appeared in the press. The Greater London Council (GLC) pushed this agenda, often openly clashing with the government. The GLC ceased to exist on 31 March 1986 but other rogue local authorities continued this work. For instance, Haringey wanted positive images of homosexuality in local schools. The government and press presented these councils as ‘loonie lefties’.

Local authority-supported LGBTQ+ youth groups also attracted a backlash. A complaint to the Department of Education and Science by Christian charity Nationwide Festival of Light objected to the Inner London Education Authority registering and supporting voluntary groups dealing with young lesbian and gay people. The National Festival of Light even asked if the aim of these youth groups was to:

release youngsters from involvement in homosexual practices, or whether it would be to confirm them in such practices and encourage them in the idea that such a way of life is natural and normal to them.

Catalogue reference: ED 232/28

Sir Keith Joseph, MP Education and Science secretary said there was nothing he could do under current legislation (catalogue reference: ED 232/28).

Attempts to legislate

In 1986 the Earl of Halsbury introduced a Private Members Bill in the Lords with the long title 'An Act to restrain local authorities from promoting homosexuality'. Correspondence in Prime Minister’s Office papers from March 1987 by Baroness Cox, a stalwart supporter of the bill, described the 'iniquitous corruption of children' as a 'matter of serious public concern' (catalogue reference: PREM 19/4734).

Officials initially felt that introducing such a bill would undermine their recent Education Act (1986) work on sex education in schools, which already sought to address some of these issues. A general election halted any further progress of the bill.

The Conservatives gained a landslide victory, mandating their approach. The topic came up at the 1987 Conservative Party conference. In her speech Thatcher said:

Children who need be taught to respect traditional moral values are being taught that they have the inalienable right to be gay

Margaret Thatcher, 9 October 1987.

In December 1987 a version of Halsbury’s bill made its way into a much broader Local Government Act, which covered an assortment of subjects. This time attempts were successful.

Wording

What played out in parliament essentially became a discussion of the legitimacy of lesbian and gay lives. Alongside intense debates about the tendering of contracts were reams of debates about the 'promotion of homosexuality'.

Records in The National Archives highlight some of the concerns prompted by the proposed legislation. At the time human rights lawyer Madeleine Colvin described it as 'the first time this century that a new piece of legislation has been enacted which specifically singles out homosexuality and lesbian and gay lifestyles for disapproval'. In the bill 'homosexuality' was used to refer to male and female same sex relationships – a rare piece of legislation to apply to lesbians too.

Discussions in Parliament focused significantly on the wording of the bill. A particular focus was the use of the word 'promoted' – could you promote a sexuality?

Both sides of the debate were cautious about the vague wording of the bill and how it could be open to misinterpretation. A coalition of organisations against the clause argued in their protest flyers that '"Promotion" is likely to be defined as anything that does not define homosexuality as unnatural or unacceptable' (catalogue reference: FCO 82/1979).

The legislation explicitly targeted families, not just sexual relationships. The final act included the phrase 'pretended family relationship'. This put into law the idea that families with same sex parents were not valid or legitimate.

Education and health care

Attempts were made, including representations from the Chairman of the Arts Council and other arts bodies, to add more specific clauses to protect literary works and educational provisions. These were rejected as it was felt they would undermine the basic principle of the bill.

The government repeatedly rejected such calls to change the wording, writing, 'we do not accept the view that clause 28 need lead to discrimination: its effect is entirely neutral' and 'a local authority with a legitimate purpose will not be at risk by clause 28' (catalogue reference: HLG 29/2675).

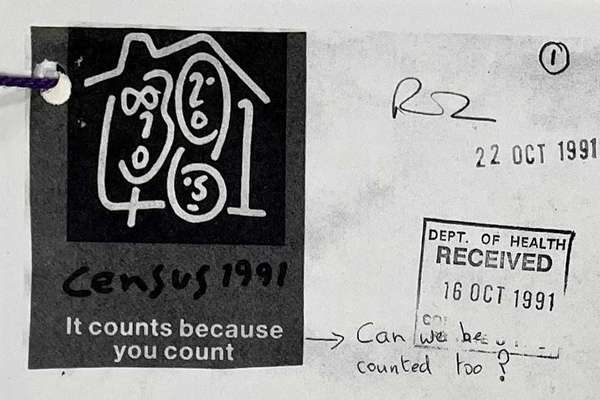

At the House of Lords Committee stage, attempts were made to make more explicit the health exemptions, especially in relation to AIDS. This was following the infamous Don’t Die of Ignorance campaigns, which showed how much education was needed.

A group of psychiatric and social work professional bodies linked to the London Borough of Greenwich wrote 'the result of clause 28 will undoubtedly increase, the number of lesbians and gay men refer to our services as clients, whilst at the same time decrease the options for help that we can give.' They described themselves as 'deeply concerned', worrying about an increased risk of suicide through isolation and forcing people into heterosexual lifestyles (catalogue reference: JA 235/96).

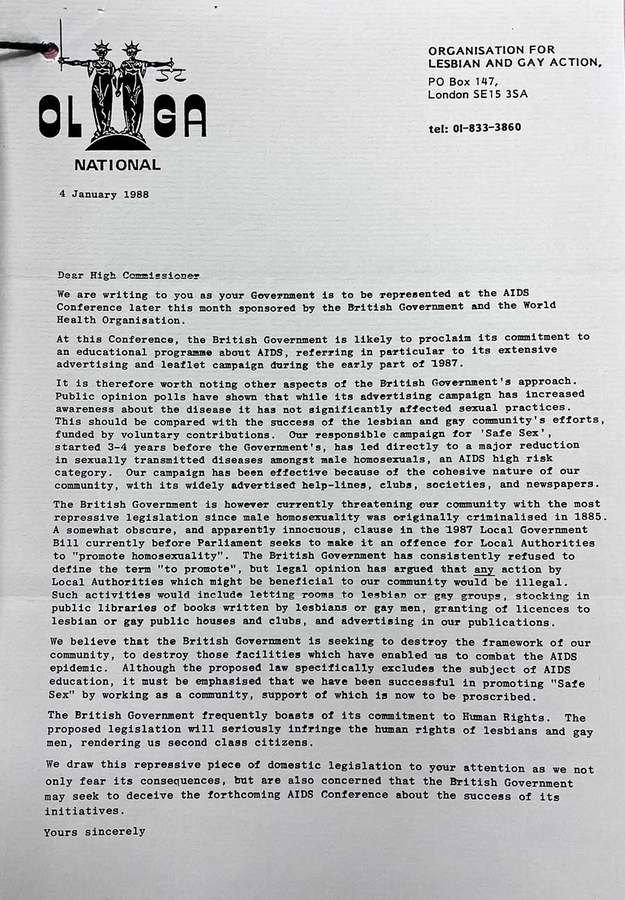

To protest the government’s action, OLGA wrote to every government representative attending the World Health Organisation conference on AIDS held in London. They argued that successes of the AIDS fight had come from working together and saw this as 'seeking to destroy the framework of our community'.

We are writing to you as your Government is represented at the AIDS conference later this month sponsored by the British Government and the World Health Organisation.

At this Conference, the British Government is likely to proclaim its commitment to an educational programme about AIDS

[…]

The British Government is however currently threatening our community with the most repressive legislation since male homosexuality was originally criminalised in 1885. A somewhat obscure, and apparently innocuous, clause in the 1987 Local Government Bill currently before Parliament seeks to make it an offence for Local Authorities to “promote homosexuality”. The British Government has consistently refused to define the term “to promote”, but legal opinion has argued that any action by Local Authorities which might be beneficial to our community would be illegal. Such activities would include letting rooms to lesbian or gay groups, stocking in public libraries of books written by lesbian or gay men, granting of licences to lesbian or gay public houses and clubs, and advertising in our publications.

We believe that the British Government is seeking to destroy the framework of our community, to destroy those facilities which have enabled us to combat the AIDS epidemic. Although the proposed law specifically excludes the subject of AIDS education, it must be emphasised that we have been successful in promoting “Safe Sex” by working as a community, support of which is now to be proscribed.

Letter by OLGA, who sent copies to every government representative attending an international summit on AIDS in early 1988, just prior to the passing of the Act (catalogue reference: JA 235/96).

The leading AIDS charity the Terrence Higgins Trust also strongly rejected the proposed legislation.

The National Council for Voluntary Organisations objected to a planned part of the clause that tried to defund voluntary groups or projects promoting homosexuality – this was successfully removed through an amendment (catalogue reference: JA 235/96).

Political opposition

Many attempts were made to soften or add clarity to the act with amendments. A letter written by a Conservative Haringey Councillor highlighted the 'fear... that it will be used by some groups as an excuse for vindictiveness and bigotry against gays' (catalogue reference: HLG 29/2676).

Labour initially did not side against Clause 28. Openly gay MP Chris Smith felt that Labour saw it as a 'diversion from demanding better conditions and rights for working-class people'.

The party belatedly declared themselves opposed to the clause after the newly formed Liberal Democrats came out in opposition to it. Simon Hughes, of the Liberal Democrats was vocally against Clause 28 and tabled several amendments.

Outside of parliament resistance was also mobilising. The Stop the Section campaign bought together a variety of groups under one uniting banner to fight the clause. Rather than silencing LGBTQ+ people, the discussion of this legislation was starting to mobilise them.

Notoriously a group of lesbians abseiled into the House of Lords during one of the final debates. Hansard simply noted an 'interruption'.

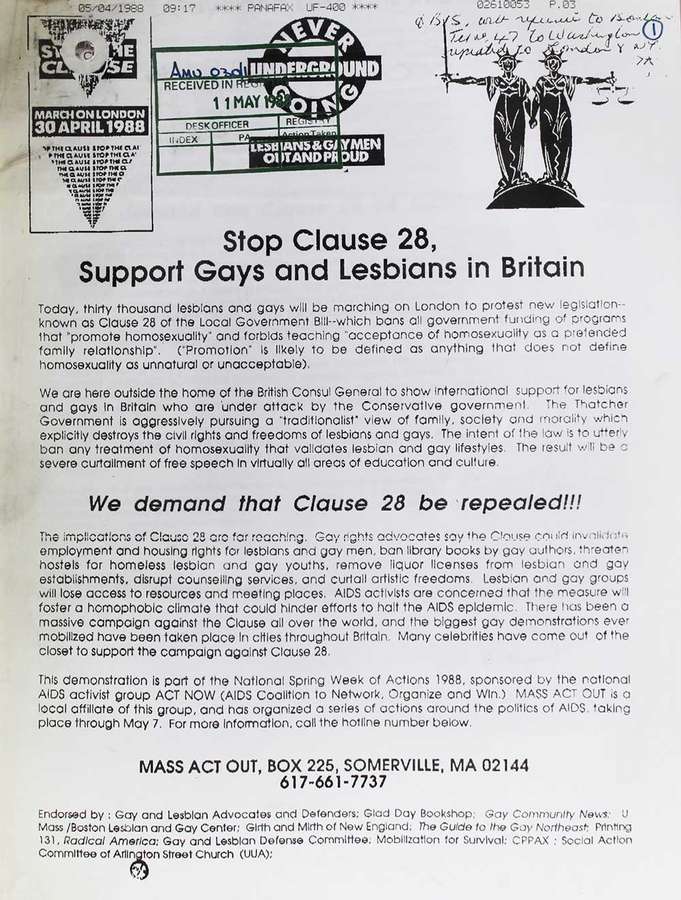

International solidarity was also evident, as seen in Foreign and Commonwealth Office records. Two British students studying in America attempted to deliver a leaflet to Philip McLean, consul general of Great Britain, Boston, Massachusetts.

One letter argued, 'Personal prejudices are becoming public policy at the expense of lives.' Attached was a protest leaflet entitled 'Stop Clause 28 Support Gays and Lesbians in Britain'. Government officials responded with a brief formal reply rejecting the claims.

We are here outside the home of the British Consul General to show international support for lesbians and gays in Britain who are under attach by the Conservative government. The Thatcher Government is aggressively pursuing a “traditionalist” view of family, society and morality which explicitly destroys the civil rights and freedoms of lesbians and gays. The intent of the law is to utterly ban any treatment of homosexuality that validates lesbian and gay lifestyles. The result will be a severe curtailment of free speech in virtually all areas of education and culture.

We demand that Clause 28 be repealed!!!

The implications of Clause 28 are far reaching. Gay rights advocates say the Clause could invalidate employment and housing rights for lesbians and gay men, ban library books by gay authors, threaten hostels for homeless lesbian and gay youths, remove liquor licenses from lesbian and gay establishments, disrupt counselling services, and curtail artistic freedoms. Lesbian and gay groups will lose access to resources and meeting places. AIDS activists are concerned that the measure will foster a homophobic climate that could hinder efforts to halt the AIDS epidemic. There has been a massive campaign against the Clause all over the world, and the biggest gay demonstrations ever mobilized have been taken [sic] place in cities throughout Britain. Many celebrities have come out of the closet to support the campaign against Clause 28.

Clause 28 leaflet advertising a solidarity protest in America, timed to coincide with one of the many protests in London (catalogue reference: FCO 82/1979).

Tens of thousands took part in demonstrations, regional rallies were held and local MPs petitioned. Ian McKellen came out live on radio. Lesbian and gay people were not going to tolerate this treatment anymore.

But despite the wide-ranging protests inside and outside parliament, on 24 May 1988 the act became law. The core of the section remained as intended. It would be in place for over a decade.

Records featured in this article

-

- From our collection

- HLG 29/2675

- Title

- Local Government Bill (No. 2) 1987: post-introduction; House of Lords; second reading and Committee stage

- Date

- 1988

-

- From our collection

- JA 235/96

- Title

- Department of Health records on Section 28

- Date

- 1988

-

- From our collection

- PREM 19/4734

- Title

- Records of the Prime Minister's office: Homosexual rights in Great Britain and Europe; part 1

- Date

- 1894 - 1994

-

- From our collection

- DPP 2/8175

- Title

- 'Playbook for Kids about Sex': charges considered for contravention of the Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act 1955

- Date

- 1983

-

- From our collection

- ED 232/28

- Title

- Complaint by Christian charity 'Nationwide Festival of Light' to Secretary of State, Department of Education and Science

- Date

- 1982

-

- From our collection

- FCO 82/1979

- Title

- Opposition to Clause 28 of the Local Government Bill 1988 by UK expatriates in the USA

- Date

- 1988

References

- Paul Baker, Outrageous!: The Story of Section 28 and Britain’s Battle for LGBT Education (London, 2022).

- Madeleine Colvin and Jane Hawksley, Section 28: A Practical Guide to the Law and its Implications (London, 1989).

- Matt Cook, A Gay History of Britain: Love and Sex between Men since the Middle Ages (Oxford, 2007).

- Dan Glass, United Queerdom: From the Legends of the Gay Liberation Front to the Queers of Tomorrow (London, 2020).

All works referenced are available in The National Archives Library