Important information

This article quotes original documents containing racially offensive language.

Early life

Nancy was 52 when she disembarked the Empire Windrush at Tilbury in June 1948, but long before then her life had caught the attention of the authorities and dominated the society pages of the transatlantic print media.

Born into the British upper classes in 1896, the daughter of Sir Bache Cunard and Maud (also known as Emerald) Alice Burke, Nancy Cunard was the only heir to the lucrative Cunard shipping business. She was a frequent traveller and enjoyed a privileged lifestyle from a young age, spending much of her adolescence in various European boarding schools.

In 1911 when her parents divorced, Nancy moved to London and was introduced to the lively literature scene through friends of her mother, whose lavish salons earned her a reputation as one of the most prominent hostesses in London.

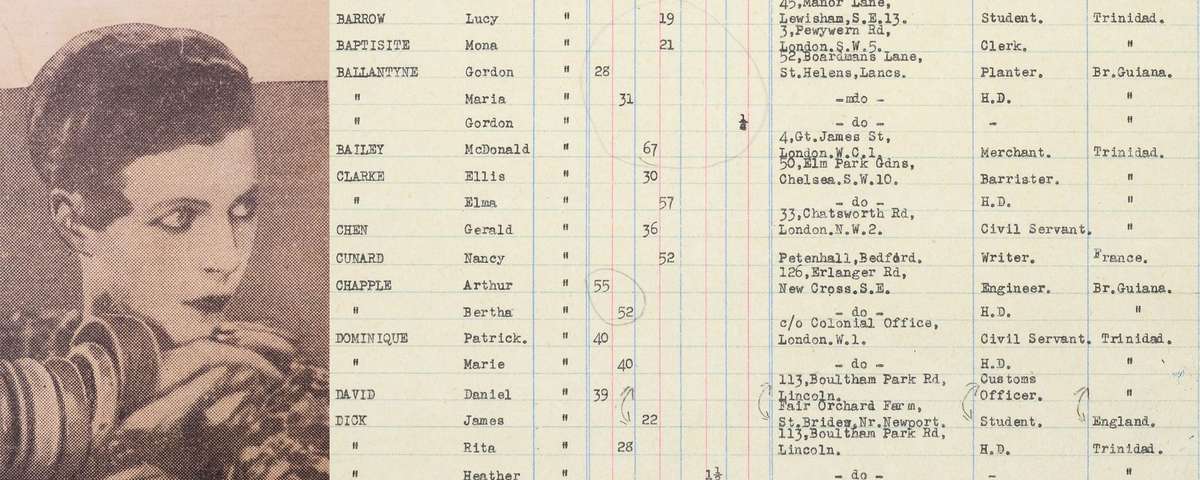

A photograph of Nancy from the Daily Express, December 15, 1933. Catalogue reference: MEPO 38/9.

After she separated from her first husband Sydney, Nancy became enmeshed with the intellectual scene in Paris. She moved to the city in 1920, becoming a muse for writers including Aldous Huxley, Samuel Beckett, and Ezra Pound, and publishing poems by her own hand.

Keen to pursue her career as an activist intellectual, she took over a publishing press specialising in the avant-garde, which she renamed Hours Press.

‘Black Man and White Ladyship’

In 1928 Nancy met Henry Crowder in Venice after hearing him play the piano with the jazz band Eddie South and his Alabamians. Knowledge of her friendship with a black gentleman quickly spread across Europe and the pair became the focus of gossip pages in the transatlantic print media. In one such episode on a May morning in 1932 Nancy met photographers and reporters to address a story which had been published that day.

The focus of the media frenzy was the publication of a small pamphlet entitled Black Man and White Ladyship. In the pamphlet Nancy wryly listed the racist protestations of her mother and the wider world to her relationship with Henry, revealing personal details about her allowance and correspondence with other members of high society.

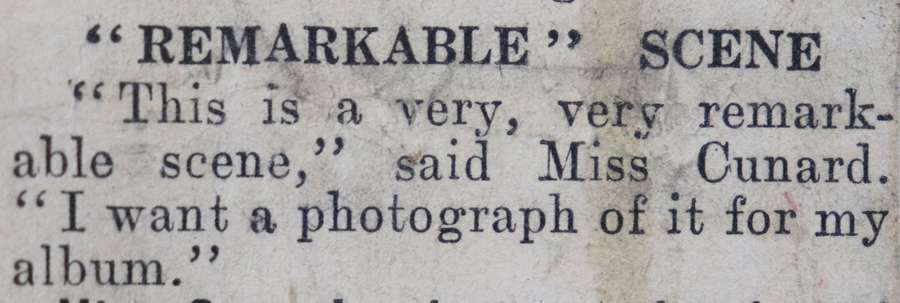

"This is a very very remarkable scene," said Miss Cunard. "I want a photograph of it for my album"

An extract from the Daily Express, 3 May, 1932. Catalogue reference: MEPO 38/9.

It was here, ‘sat upon a glass-topped table’ that she also expressed her desire to provide support for the Scottsboro Boys – a case concerning seven young black boys, all under the age of 19, sentenced to death for the alleged assault of two young white women in Alabama in 1931.

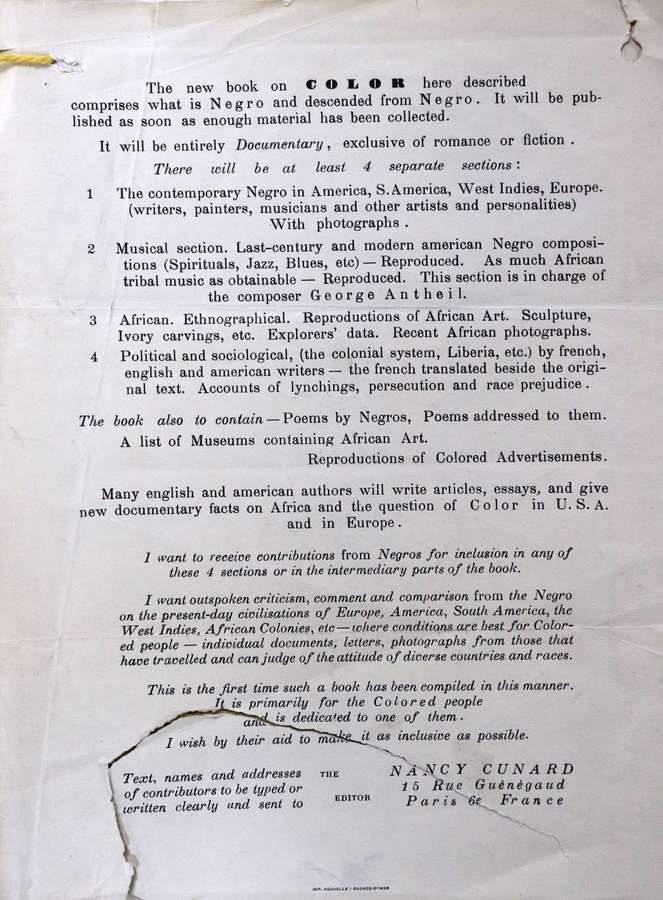

Nancy asserted she would devote her stay to collecting material for her book ‘for colored people’, which would contain outspoken criticism, accounts of lynchings, and of course, poetry.

The new book on COLOR here described comprises what is Negro and descended from Negro. It will be published as soon as enough material has been collected.

It will be entirely Documentary, exclusive of romance or fiction.

There will be at least 4 separate sections:

- The contemporary Negro in America, S. America, West Indies, Europe. (writers, painters, musicians and other artists and personalities). With photographs.

- Musical section. Last-century and modern american Negro compositions (Spirituals, Jazz, Blues, etc) – Reproduced. As much African tribal music as obtainable – Reproduced. This section in charge of the composer George Antheil.

- African. Ethnographical. Reproductions of African Art. Sculpture, Ivory carvings, etc. Explorers’ data. Recent African photographs.

- Political and sociological, (the colonial system, Liberia, etc.) by french, english and american writers – the French translated beside the original text. Accounts of lynchings, persecution and race prejudice.

The book also to contain – Poems by Negros, Poems addressed to them.

A list of Museums containing African Art

Reproductions of Colored Advertisements

Many english and american authors will write articles, essays and give new documentary facts on Africa and the question of Color in U.S.A. and in Europe.

I want to receive contributions from Negros for inclusion in any of these 4 sections or in the intermediary parts of the book.

Nancy’s anthology, ‘Negro’, was published in 1934 and it collected works by many different contributors including W. E. B. DuBois, Langstone Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. Catalogue reference: MEPO 38/9.

This is the first time such a book has been compiled in this manner. It is primarily for the Coloured people and is dedicated to one of them. I wish by their aid to make it as inclusive as possible.

The attention did not quell and on their return to London that year, Nancy and Henry were met with ‘hysteria’, with people calling their hotel daily to discover the intended onward journeys of the pair. Writing in W. E. B. DuBois’ African American Journal The Crisis, Nancy also mentioned briefly her choice to ignore ‘Rumours of detectives, whispers of police’ (The Crisis, Vol.38, Issue 9, September 1931).

Police attention

Some of Nancy’s interactions with police through the 1930s are captured in the file MEPO 38/9.

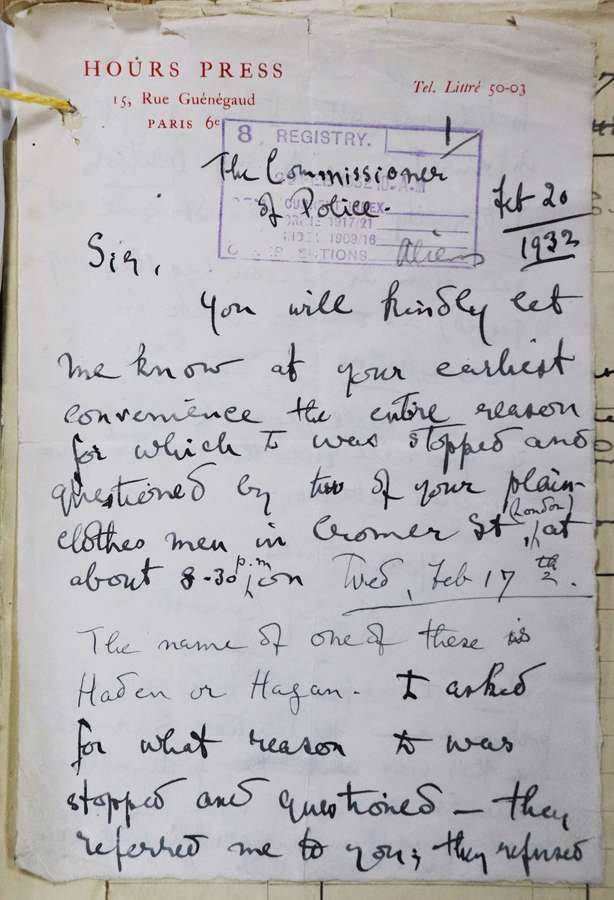

In February 1932 she was stopped in London by officers who had been instructed to ascertain her identity. After the incident Nancy wrote to the Commissioner of Police:

HOURS PRESS

15 Rue Guénégaud

Paris 6e

The Commissioner of Police

Feb 20 1932

Sir,

You will kindly let me know at your earliest convenience the entire reason for which I was stopped and questioned by two of your plain clothes men in Cromer St (London) at about 8.30pm on Tues, Feb 17th.

The name of one of these is Haden or Hagan, I asked for what reason I was stopped and questioned – they referred me to you […]

Nancy’s handwritten letter to the Commissioner of Police. Catalogue reference: MEPO 38/9.

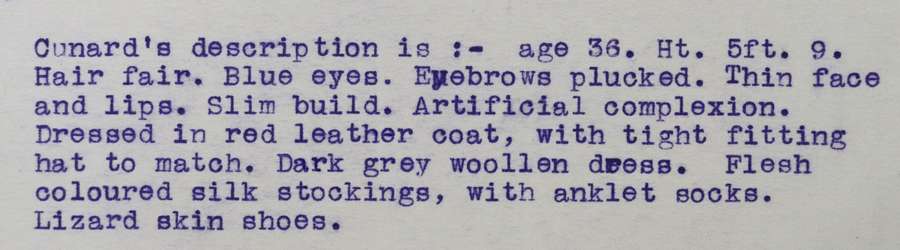

The complaint of 1932 was quickly dismissed, but the encounter was recorded in detail by the officers involved. We can only imagine what the scene may have looked like on Crowder Street on that wintry evening in February – Nancy with her distinctive short haircut, dressed in a ‘red leather coat’, matching hat and ‘Lizard skin shoes’. She demanded to know the reasons for which she was being questioned by police, while her companion Gerald Bradley – a known communist – gently encouraged her to show her passport to the gentlemen.

Nancy’s clothes gained her the ‘reputation of advanced ideas of dress’ and officers following Nancy’s movements often made detailed notes about her clothing.

Cunard’s description is:- age 36. Ht. 5ft. 9. Hair fair. Blue eyes. Eyebrows plucked. Thin face and lips. Slim build. Artificial complexion. Dressed in red leather coat, with tight fitting hat to match. Dark grey woollen dress. Flesh coloured silk stockings, with anklet socks. Lizard skin shoes.

The police report from February 1932 describing Nancy’s appearance. Catalogue reference: MEPO 38/9.

Although officers stated that they approached Nancy based on the Aliens act 1919 in 1932, it was her involvement with anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist organisations that captured the attention of the police and MI5 and informs most of the file MEPO 38/9.

In 1933 for example, police record that she is collecting money on behalf of the Scottsboro Boys. MI5 was particularly interested in her plans to form the Negro Welfare Club and bookshop. Many of the reports also mention that Nancy had ‘no settled address’ and officers followed her to make note of where she was sleeping, what establishments she visited and who she interacted with, mostly the black men with whom she associated.

The constant surveillance Nancy was subject to across the 1930s and early 1940s reflected wider social anxieties about the relationships white women shared with black men in Britain at the time.

Parties and activism

Police officers also compiled newspaper clippings articles detailing Nancy’s grand parties in various addresses across London, painting a vivid picture of her social circle that included artists, intellectuals, and activists.

In 1933 officers even heard a rumour that Josephine Baker, the French singer, actress and dancer, might be persuaded to attend one of Nancy’s soirees.

But Nancy did not use these meetings only to entertain. Talks were given on various injustices such as racial discrimination in Britain and the Meerut prisoners – a group of Indian trade union leaders arrested by the British government. Money was raised to support a variety of causes, and some of these gatherings continued into the dawn.

In the mid 1930s, reports started to cover Nancy’s work as a journalist covering the civil war in Spain and her support for the Republican cause. She raised funds on behalf of the International Brigade and organised the sending of food parcels and relief missions to refugee camps, where she reported on atrocious conditions on behalf of the Manchester Guardian.

Her experiences informed a call out for writers and artists to take sides in the Spanish Civil War, the replies of which she published in 1937.

Tracing Nancy in the archive

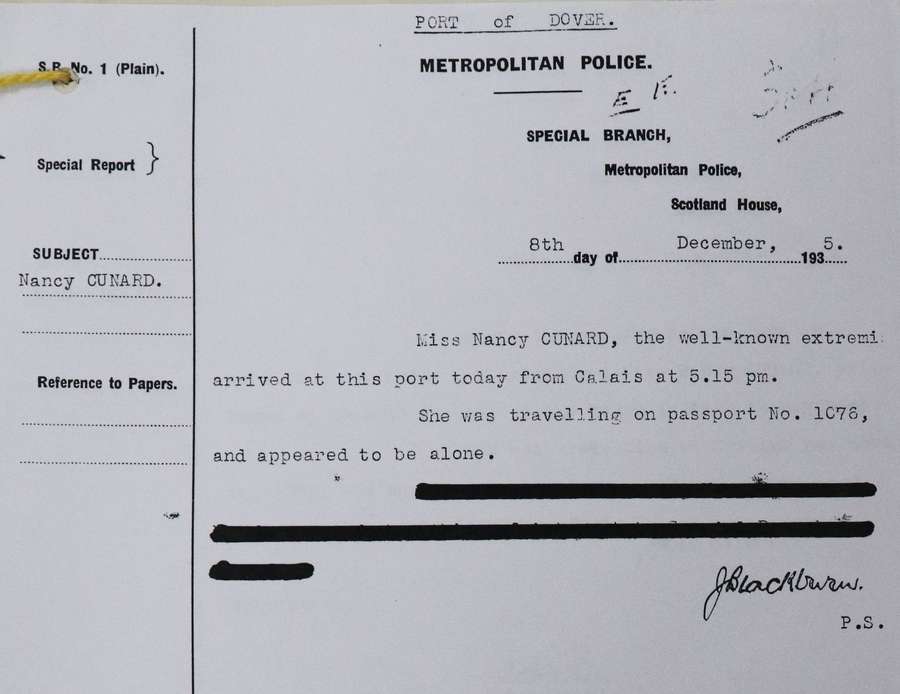

Some details in Nancy’s file have been redacted, meaning there is information blotted out and hidden from view. The exempt details of her file in MEPO 38/9 leave questions as to Nancy’s life, her involvement in political organisations and the investigations of the police.

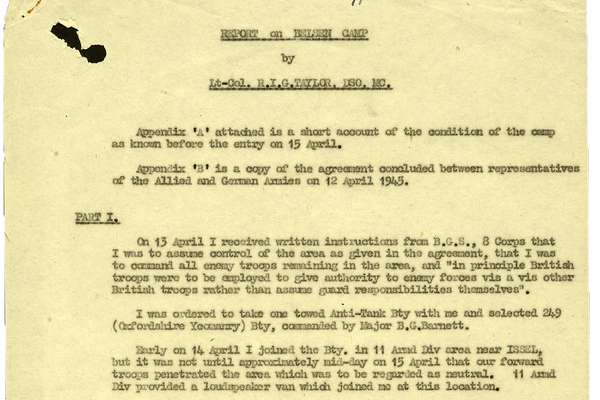

Special Report

Subject Nancy Cunard

Port of Dover

Metropolitan Police

Special Branch,

Metropolitan Police,

Scotland House,

8th day of December,1935

Miss Nancy Cunard, the well-known extremist arrived at this port today from Calais at 5.15 pm.

She was travelling on passport No. 1076, and appeared to be alone.

[Redacted]

A redacted memo on Nancy Cunard in which she is described as an 'extremist'. Catalogue reference: MEPO 38/9.

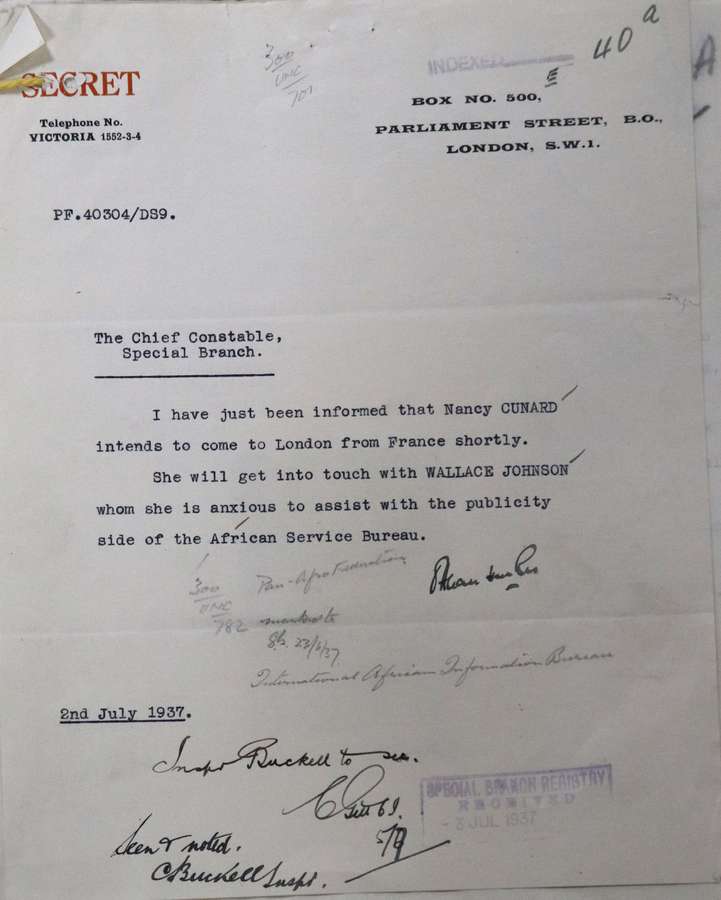

Her association with black activists was of particular interest to MI5. A memo from Box 500 – the SW1 Post Office box for MI5 – shows intelligence that the agency had on Nancy. This included her movements and who she wanted to talk to, such as the Sierra Leonian-born activist and journalist I. T. A. Wallace-Johnson.

The Chief Constable,

Special Branch.

I have just been informed that Nancy CUNARD intends to come to London from France shortly.

She will get into touch with WALLACE JOHNSON whom she is anxious to assist with the publicity side of the African Service Bureau

A memo to the Chief Constable of Special Branch on Nancy’s movements. Catalogue reference: MEPO 38/9

However, her impact as an activist is evident through her presence across the vast collection at The National Archives. For example, Nancy is also mentioned in correspondence regarding the presence of communist influence across the British Empire and specifically in Jamaica, where strikes and civil disobedience bought industries to a halt across the island in the 1930s and early 1940s (catalogue reference: CO 295/606/4)

As an outspoken anti-fascist and champion of African diasporic culture and peoples, she was a target for the Nazis. During the occupation-pillage of her house in Réanville during World War II, decades-worth of her work covering the Spanish Civil War was destroyed and scattered while the houses of her neighbours remained untouched.

The loss of such work must have affected Nancy on a deep level. Indeed, her struggles with mental health, extensive travelling, and substance abuse might have contributed to her early death in 1965 in Paris.

We may never know what kind of conversations or interactions occurred between Nancy and her fellow passengers in A class aboard the Empire Windrush in 1948. However, her vivid presence in records held by The National Archives speaks to an individual who should not be dismissed as a socialite masquerading as an activist, but as an advocate for causes that took her across the world and placed her under the scrutiny of the police and British intelligence service in the 20th century.

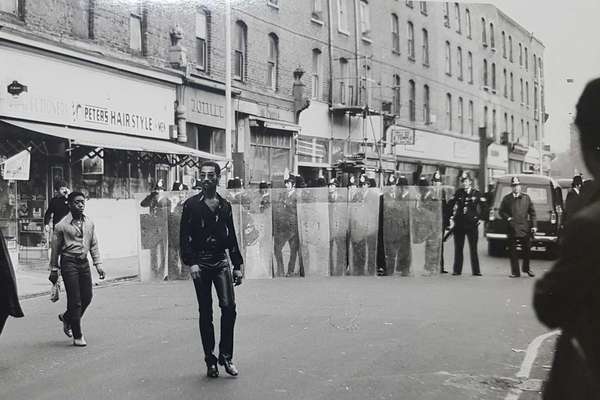

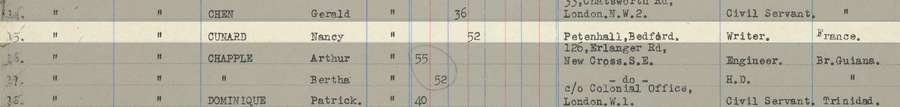

15. CUNARD Nancy

52

Petenhall, Bedford

Writer

France.

Nancy Cunard's entry in the 1948 Windrush passenger lists. Catalogue reference: BT 26/1237

Records featured in this article

-

- From our collection

- MEPO 38/9

- Title

- Nancy Cunard's Metropolitan Police File

- Date

- 1932 – 1947

-

- From our collection

- BT 26/1237

- Title

- Inwards Passenger Lists, Empire Windrush, London

- Date

- 21 June 1948

-

- From our collection

- CO 295/606/4

- Title

- Communist activity in the British West Indies

- Date

- 22 March 1938 – 24 June 1938

Further reading on Nancy Cunard

Anne Chisholm, Nancy Cunard: A biography (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981).

Anne de Courcy, Five love affairs and a friendship: Scenes from the Paris life of Nancy Cunard (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2022).

Anne Donlon, “Things and Lost Things: Nancy Cunard’s Spanish Civil War Scrapbook.” The Massachusetts Review, vol. 55, no. 2, 2014, pp. 192–205.

Nancy Cunard, Poems of Nancy Cunard: From the Bodleian Library, edited with an Introduction by John Lucas (Nottingham: Trent Editions, 2005).

Read more

Windrush 75

In this collection of articles and resources, discover the history of Windrush 75 years on, told through the government records that capture this important moment in British and global history.