Record revealed

List of people summoned to the 1265 Parliament

This document records the first time that citizens outside of the elites were called to join an English parliament – without being asked to support new taxes.

Images

Image 1 of 4

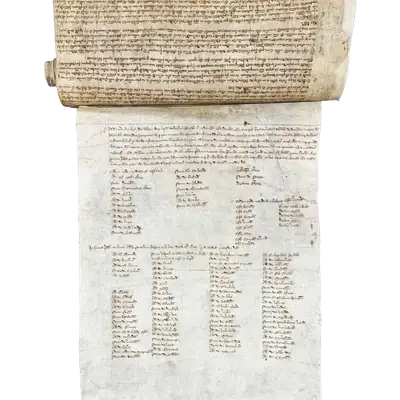

The close roll from Chancery recording who was summoned to join the 1265 Parliament.

Image 2 of 4

Sheet of parchment attached to the main roll listing which officials from the church, nobility and ordinary society had been summoned to join the parliament.

Image 3 of 4

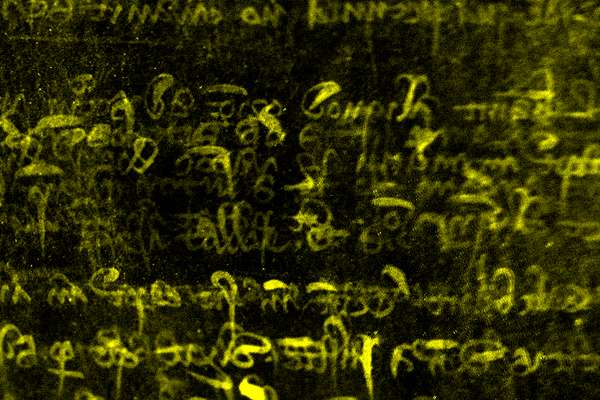

Top of the parchment listing which officials had been summoned to join the parliament.

[The text uses abbreviations commonly used by Chancery clerks, expanded here]

Henricus Dei gracia rex Anglie, dominus Hibernie et dux Aquitannie, venerabili in Christo patri R. eadem gracia episcopo Dunelmensi salutem.

Cum post gravia turbacionum discrimina dudum habita in regno nostro [...] et jam sedata, benedictus Deus, turbacione predicta super deliberacione ejusdem salubriter providenda, et plena securitate tranquillitatis et pacis ad honorem Dei et utilitatem totius regni nostri firmanda et totaliter complenda ac super quibusdam aliis regni nostri negociis que sine consilio vestro et aliorum prelatorum et magnatum nostrorum nolumus expediri, cum eisdem tractatum habere nos oporteat ; vobis mandamus, rogantes in fide et dilectione quibus nobis tenemini, quod omni occasione postposita et negociis aliis pretermissis, sitis ad nos Lond' in octabis Sancti Hillarii proximo futuris, nobiscum et cum predictis prelatis et magnatibus nostris quos ibidem vocari fecimus super premisses tractaturus et consilium vestrum impensurus. Et hoc sicut nos et honorem nostrum et vestrum necnon et communem regni nostri tranquillitatem diligitis, nullatenus omittatis. Teste rege apud Wygorniam viij. die Decembris.

Eodem modo mandatum est episcopo Karleolensi,

abbati Sancta Marie Ebor',

[...]

Eodem modo mandatum est subscriptis :

episcopo Londoniensi,

episcopo Wyntoniensi,

[...]

Henry, by the grace of God, king of England, lord of Ireland and duke of Aquitaine, greetings in Christ to the venerable father R[obert], by the same grace, bishop of Durham.

When, after the great disturbance which, sometime before, had taken place in our kingdom [...] now quelled, thanks be to God, by the resolve of the same [King Henry] restoring to spiritual health, full security, tranquillity, and the peace of our realm, to the honour of God and to the advantage of everyone, firmly and perfectly accomplished; and upon certain other affairs of our kingdom which, without your counsel and that of the other prelates and magnates of our realm, we do not wish to deal with hastily, when it is essential that with them we are to have discussions, we order you, and request in faith and with the love which you hold for us, that putting aside every occasion and neglecting other business, you will come to us in London on the octaves of St Hilary next, with us and with our aforesaid prelates and magnates, whom we have called there, intending to debate these matters and secure your counsel. And this you will in no way neglect, since you love us and our honour and yours, as well as the common tranquility of our kingdom. Attested by the king at Winchester on the 9th day of December.

The same is ordered to the bishop of Carlisle,

To the abbot of St Mary’s York,

[...]

The same is ordered to the below:

The bishop of London,

The bishop of Winchester,

[...]

Image 4 of 4

Close-up of the order to send citizens to the parliament.

Item mandatum et singulis vicecomitibus per Angliam quod venire faciant duos milites de legalioribus, probioribus et dicre tioribus militibus singulorum comitatuum ad regem Lond' in octabis predictis, in forma supradicta.

Item in forma predicta scribitur civibus Eboraci, civibus Lincolnie et ceteris burgis Anglie quod mittant in forma predicta duos de discretioribus, legalioribus et probioribus tam civibus quam burgensibus suis.

Item in forma predicta mandatum est baronibus et probis hominibus Quinque Portuum, prout continetur in brevi inrotulato inferius.

Also a command to every sheriff throughout England to send two of the more law-worthy, honest and prudent knights from each of the counties to the king of London in the aforesaid eight days, in the form aforesaid.

Likewise, in the aforesaid form, it is written to the citizens of York, the citizens of Lincoln, and the other burgesses of England that they should send in the aforesaid form two of the more prudent, law-worthy and honest fellow citizens or burgesses.

Likewise, in the aforesaid form, the command was given to the barons and noblemen of the Cinque Ports, as it is contained in the brief written below.

Why this record matters

- Date

- December 1264

- Catalogue reference

- C 54/82

In 1264 England was in crisis. In May of that year, after years of unrest within the ruling elite, King Henry III had been defeated at the Battle of Lewes and taken prisoner. The Earl of Leicester (who was also his brother-in-law), Simon de Montfort, had usurped power, ruling in Henry’s name while he held the king captive.

But this did not mean an end to the civil turmoil. De Montfort had many enemies, and there were powerful forces still loyal to Henry. De Montfort needed to give his government the veneer of legitimacy, and one means of doing that was to call a parliament. These great councils were a tradition of English government reaching back centuries. By holding one, de Montfort could give the impression that he was ruling with the guidance and consent of representatives from across the kingdom.

In December 1264, Chancery, the government writing office, prepared writs to summon people to a parliament planned for early 1265. Writs were sent to the sheriffs, who were the key royal officials in the counties, ordering them to send ‘two of the more law-worthy, honest and prudent knights from each of the counties’. More writs were sent to the ‘citizens’ of York, Lincoln and other English boroughs (towns), who were also ordered to send two of their most ‘prudent, law-worthy and honest fellow citizens or burgesses’. Yet more writs were sent to summon de Montfort’s baronial allies, churchmen, and citizens of the Cinque Ports (five Channel ports that owed particular obligations to the Crown, in return for certain privileges).

As the writs were criss-crossing the country, a clerk back at Chancery recorded the details of them – what had been sent where, to whom and when – on one of the huge Chancery rolls that existed for just this purpose. The writs had been sent as ‘letters close’, meaning that they were folded up, with the Great Seal across the closure, preventing anyone reading them en route to their intended recipient. They were enrolled (recorded) on the ‘close roll’ for the 49th year of the reign of Henry III. Thousands of these rolls are preserved at The National Archives, recording in incredible detail all manner of business by medieval royal government.

This close roll provides clear evidence that the 1265 parliament had representatives from across the country, and from different social groups. It was not purely a council made up of elite aristocrats. It would not be true to say that this was the first parliament at which there was broader representation – knights had certainly been included on some occasions before, and possibly also some citizens of the boroughs. However when they had been summoned to previous parliaments it was generally because the king was trying to get their support for new taxation (medieval monarchs were constantly short of cash). This parliament was different: de Montfort was not looking for money, he was seeking the advice and guidance of representatives of the kingdom he had usurped.

Only a few months after this parliament the Battle of Evesham was fought. The forces of de Montfort and his allies were defeated by forces led by the Lord Edward, Henry III’s son and heir. De Montfort himself was killed in the battle. Royal government under Henry III was restored. Nonetheless, it gradually became established that people outside the aristocratic elites would be summoned to parliaments. Despite his bloody end, Simon de Montfort was to have a lasting impact on the development of parliamentary democracy.

Featured articles

Record revealed

A medieval Irish roll with hidden grievances

This roll provides a glimpse into how medieval Ireland was governed, but today plays a starring role in the development of scientific methodologies.