Important information

This article details past homophobic and transphobic attitudes, gendered stereotypes and the policing of queer communities. Some records contain uncomfortable and offensive language. Original language is preserved here to accurately represent our records and to help us fully understand the past.

A kaleidoscope of colour

The 1930s saw a series of balls at the Royal Albert Hall filled with fancy dress, dancing to the early hours and transgressive clothing. These events were for the nation’s servants. Described as a kaleidoscope of colour, they were held annually and became very popular. As their popularity increased, so too did their attraction to society's outsiders.

‘In the bars small groups of young men dressed in coloured silk blouses and tight hipped trousers, were drinking from small glasses. One had a small hand mirror and comb. Their lips were rouged and faces painted.’

Metropolitan Police file. Catalogue reference: MEPO 2/3281

Individuals perceived as men danced with other men, dressed in unconventional, gender-playful outfits, and wore makeup. The range of sexuality and gender expressions on display might best be represented today using the umbrella term 'queer'. Against the host’s initial intentions, for one night of the year, the Royal Albert Hall became a queer working-class haven.

Photograph of the Royal Albert Hall, Kensington, London, where the balls took place from 1930. Photo dated 1899. Catalogue reference: COPY 1/442/591

Servants' turn to celebrate

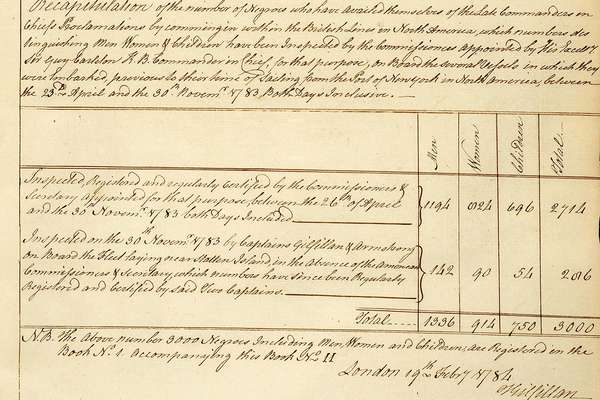

From 1923 until 1938, Lady Malcolm's Servants Balls were held at some of London’s finest hotels and ballrooms. Formal gatherings for servants were not unheard of, but these were on an entirely different scale. According to an article in the Gentlewoman, the balls were designed ‘to lighten the weary hours of those who commonly see their mistresses go out to balls and parties’. These dances were a rare spectacle that centred working-class individuals. Many staff in the domestic trade attended, from parlourmaids, butlers, footmen, chauffeurs and valets to cooks and housemaids. Even servants from the royal household joined in.

Lady Jeanne Marie Malcolm, political hostess, social reformer and socialite, was the organiser. She was the daughter of famed actress Lillie Langtry, and was married to influential Scottish politician Sir Ian Zachary Malcolm. The 1911 census shows that their household had ten servants at the time, including a lady’s maid and a footman. As well as giving them (and others like them) space to enjoy themselves, the events raised money for charity, with proceeds going to the West End Hospital for Nervous Diseases.

Jeanne Marie (née Langtry), Lady Malcolm, by Bassano Ltd. © National Portrait Gallery, London (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 DEED)

Dancing would take place into the early hours, with the event closing at 3am. The late timings were partly designed to fit around the working patterns of domestic staff, to increase the chances of them being able to attend (and still be able to complete their household duties). Wealthy households would fund their workers to go, with some even loaning them evening dresses.

Lady Malcolm's balls proved hugely successful, growing in scale year after year. By 1930 they had outgrown previous venues and were taking place in the Royal Albert Hall. They were heavily reported in newspaper columns under headings such as ‘The Gossip of London’ and ‘Men and Women of To-Day’. Servants travelled to them from across the country, from as far away as Aberdeen.

Involving the authorities

The National Archives holds records about these balls because they feature in Metropolitan Police files. Initially, Sir Ian Malcolm approached the police in 1932 asking for protection of his private property on the night of the ball. This was because the previous year, while living at Onslow Square, South Kensington, their home had been burgled. The Servants Balls were a well-known society fixture – it would have been obvious that the Malcolms’ house would be left empty and vulnerable. Unhappy with the ‘insufficient’ police help after the initial burglary, Sir Malcolm continued to ask for police support year on year. Behind the scenes, police noted that the couple were ‘not too easy to deal with’.

In 1933 Lady Malcolm visited the Met as she wanted to explain something ‘personally’. She visited Lord Hugh Trenchard, Metropolitan Police Commissioner at the time, requesting the services of two officers to be on duty at the ball ‘so that they could prevent unattractive characters from entering’. Even with the suggestion of private payment, the police were not happy with this use of their resources. They suggested using ex-police officers.

An anonymous letter was also sent to the commissioner. The letter used deeply homophobic language, representing attitudes that would have been common at the time, asking:

‘Are the Police really going to allow the disgraceful scenes, of previous years of degenerate Boys and Men in female attire parading about at Lady Malcolm’s Servants Ball, at the Albert Hall tomorrow night? Such exhibitions are degrading in the extreme.’

Metropolitan Police file, 1933. Catalogue reference: MEPO 2/3281

By this time, the balls were drawing more people exhibiting same-sex desire and demonstrating transgressive gender expression. The organisers and general public had a growing awareness of it. By 1936, it was noted that ‘this Dance attracts more men of the perverted type, than any other held at the Royal Albert Hall’.

Subverting public spaces

The unique atmosphere created at these balls helped to develop a sexually open, gender-fluid and non-hierarchical space. A summary written by the police commissioner in 1934 described the festivities:

‘The Ball is a fancy dress affair and closely approximate in size to the Police Ball. Prizes are offered for the best dress, the most original turn-out and so on, the Judges being as a rule leading members of the theatrical profession. In 1933, for instance, among the Judges were Miss Irene Vanbrugh, Mr. Willie Clarkson, Mr. George Belcher and Miss Gladys Cooper.’

Metropolitan Police file. Catalogue reference: MEPO 2/3281

With their late-night dancing, fancy dress competitions and pageants, these balls offered the perfect guise to dress and act in ways that were not generally socially acceptable. Police noted: ‘ “Homo-Sexualists” generally seem to be attracted to Costume Balls’.

Fancy dress was encouraged, in part because it avoided the need for prohibitively expensive formal evening wear. Each year the fancy dress was said to become more and more elaborate. Domestic workers often humorously offered a social commentary on their employment through their fancy dress – dressing as items related to their service, such as cleaning equipment or even alarm clocks. On other occasions costumes would question defined gender roles, with individuals perceived to be men wearing dresses.

Photograph from The Bystander magazine depicting Lady Malcolm (centre), her daughter and guests in fancy dress, 1938. Source: Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

One individual, Lady Austin, possibly attended these balls. We know about them from another series of queer events that they organised: gatherings of Lady Austin's camp boys. Lady Austin attended these dances in alternative masculine and feminine dress, and implied that their name was born out of attending Lady Malcolm’s Servants Ball or Chelsea Arts Ball. Austin describes themselves as male but used this feminine identity at events. Although we don’t know details of other specific partygoers in attendance, this kind of dress and drag persona seems consistent with other individuals that the police were observing.

The large number of attendees likely offered some protection, with crowds of 4,000–5,000 upwards in attendance. As a servants’ ball, this space was already subverting social hierarchies and ‘master/servant’ dynamics. Lady Malcolm was reported in the press as dancing with her butler. The destabilising of the accepted social order in this space, for one night of the year, may have helped create an atmosphere where guests felt able to act differently.

Policing queerness

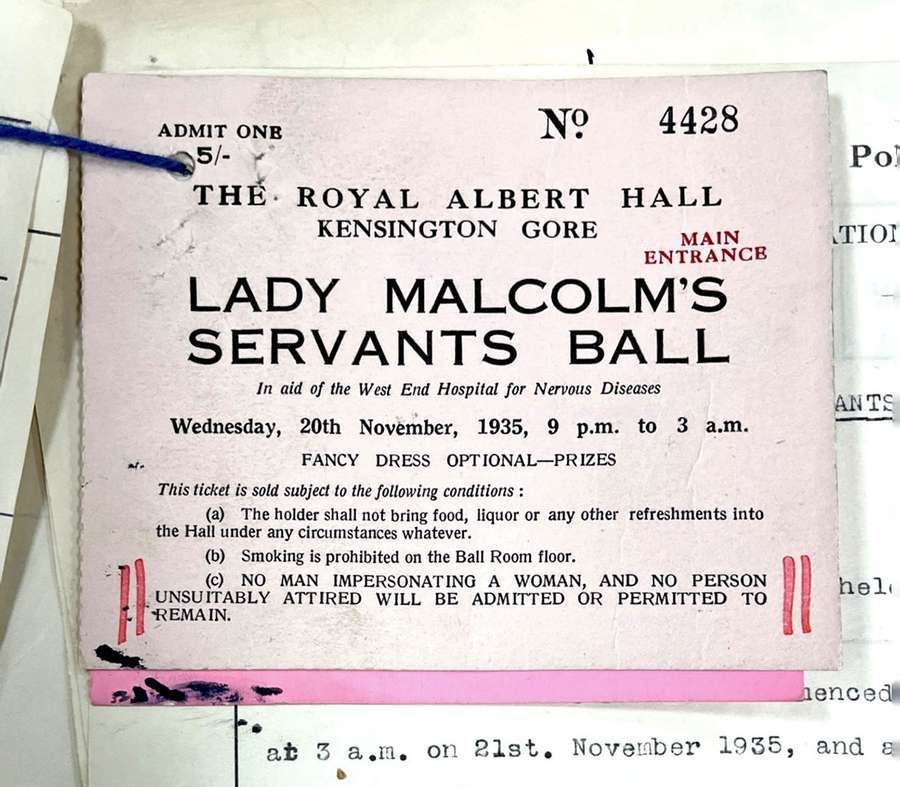

By 1935, tickets to the ball contained the following words in clear capital letters:

NO MAN IMPERSONATING A WOMAN, AND NO PERSON UNSUITABLY ATTIRED WILL BE ADMITTED OR PERMITTED TO REMAIN.

LADY MALCOLM'S SERVANTS BALL

in aid of the West End Hospital for Nervous Diseases

Wednesday, 20th November, 1935, 9 p.m. to 3 a.m.

FANCY DRESS OPTIONAL—PRIZES

This ticket is sold subject to the following conditions :

(a) The holder shall not bring food, liquor or any other refreshments into the Hall under any circumstances whatever.

(b) Smoking is prohibited on the Ball Room floor.

(c) NO MAN IMPERSONATING A WOMAN, AND NO PERSON UNSUITABLY ATTIRED WILL BE ADMITTED OR PERMITTED TO REMAIN.

Ticket for the 1935 Lady Malcolm’s Servants Ball, including text to deter subversive dressing. Catalogue reference: MEPO 2/3281

The organising committee were not pleased with the kind of people they felt were increasingly in attendance, and this was one way they sought to address it. A dystopian-sounding Board of Scrutineers formally controlled what costumes were allowed. One costumed individual drew the attention of the board as they were ‘dressed in such a fashion as might become indecent should the cloak fall. He was requested to leave and did so.’ Others drew comments on their manner and facial appearance. The way people acted, and the clothes and makeup they wore, could all have been read as homosexual signifiers.

By 1936 staff were put in post to patrol the corridors and bars. All curtains in the front of the venue's boxes were removed prior to the function, so that occupants and their actions could be plainly seen from all parts of the venue. We can only imagine the type of behaviour they were hoping to prevent!

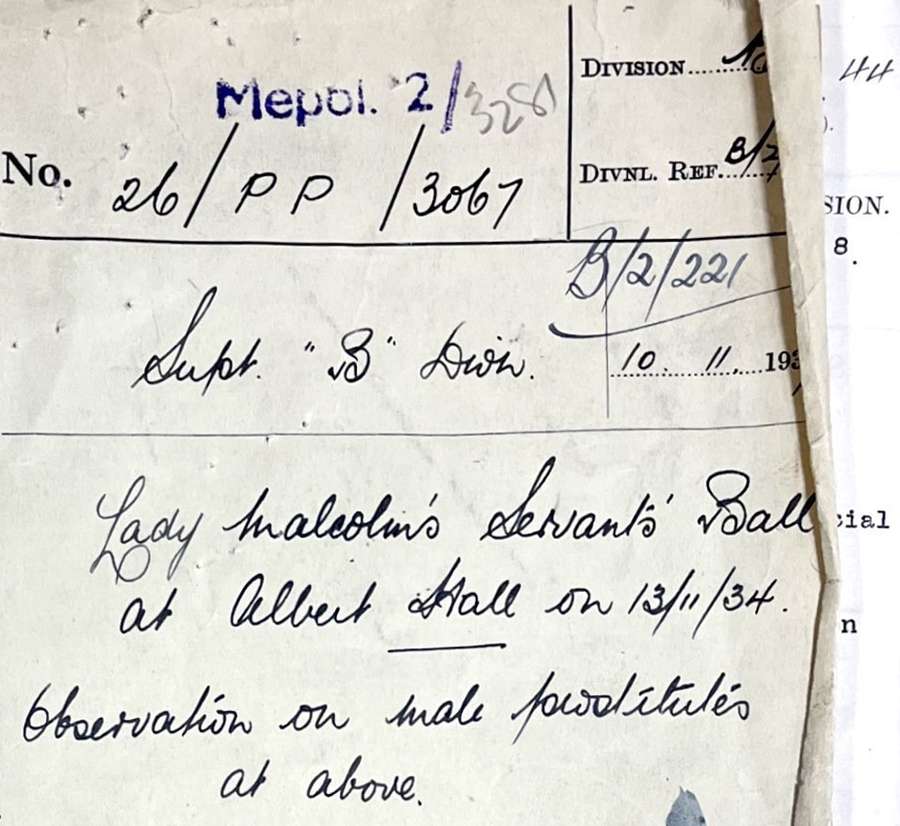

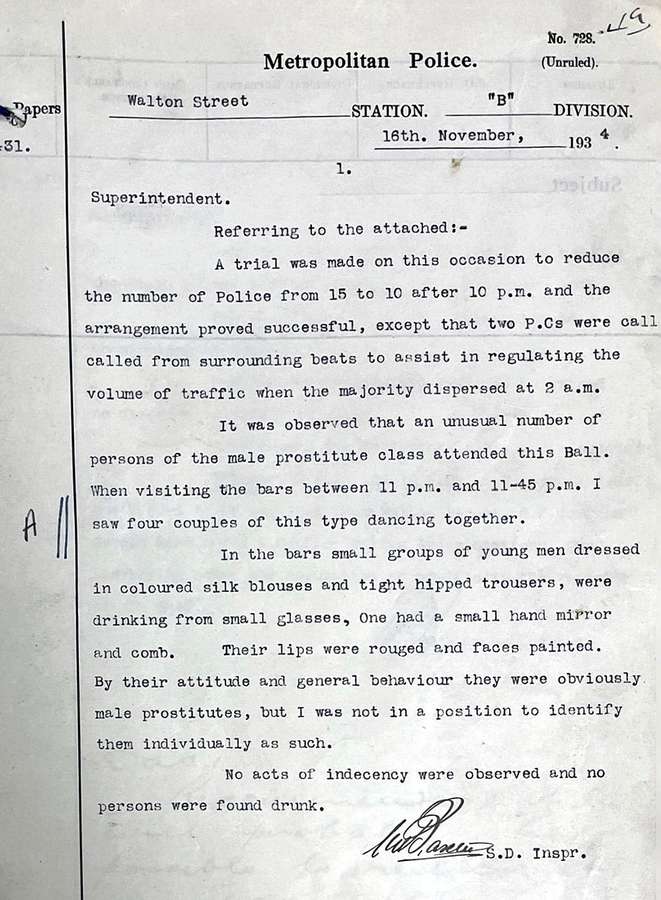

Organisers were also concerned about male sex workers. A whole subfile in the Metropolitan Police records is entitled ‘Observation on male prostitutes’. The divide between same-sex acts, male sex workers soliciting other men, and displays of gender non-conformity, were all blurred in the eyes of the police. Sex between men, whether money exchanged hands or not, was all criminalised.

Metropolitan Police subfile cover, entitled ‘Observation on male prostitutes’. Catalogue reference: MEPO 2/3281

Despite this, police reports tend to end with observations that only a handful of arrests were made (often for foul language or drunkenness) and that no disorder was noted. This suggests that, while there were attempts to police the space, individuals managed to successfully claim sections of the event as their own.

It was observed that an unusual number of persons of the male prostitute class attended this Ball. When visiting the bars between 11 p.m. and 11-45 p.m. I saw four couples of this type dancing together.

In the bars small groups of young men dressed in coloured silk blouses and tight hipped trousers, were drinking from small glasses, One had a small hand mirror and comb. Their lips were rouged and faces painted. By their attitude and general behaviour they were obviously male prostitutes, but I was not in a position to identify them individually as such.

No acts of indecency were observed and no persons were found drunk.

Metropolitan Police report on the 1934 Servants Ball, including references to male sex workers. Catalogue reference: MEPO 2/3281

The wider queer scene

These balls were far from the only night on the social calendar of queer revelers, but they were particularly public, at a prominent, commercial venue. They were also controversial for creating a space that centered the working classes. The records we hold reveal an underlying fear about sexual deviance among the lower classes, especially when they were working in upper-class households.

There was another ball at the same venue that attracted controversy: the annual New Year's Eve Chelsea Arts Ball. This calendar fixture attracted ‘the Bohemian class in fancy dress’, with annual themes varying from ‘sun worship’, ‘flaming youth’ to ‘physical perfection’. It similarly drew police scrutiny. In 1935 it was reported: ‘A few of both sexes were scantily clad but all were within the bounds of decency’ (Catalogue reference: MEPO 2/3278).

New Year's Eve at the Chelsea Arts Ball, 1923. Source: Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

It isn’t clear how such gatherings were communicated through queer networks. Year on year, though, the presence of individuals deemed to be of an ‘undesirable type’ increased at the balls, suggesting that the message spread successfully. Other working-class trades with queer networks, such as the hotel profession, found innovative ways to communicate their gatherings, and we can assume that this was the case for domestic workers as well. Word of mouth was surely an important component, at a time when it was risky to write about your queerness, sexuality or gender diversity.

Other queer balls occasionally took place at hired venues, but more commonly noted in the National Archives collections are underground, makeshift bars or clubs – quickly set up and ready to be closed at any moment. For a thorough survey of queer spaces in 1920s–1950s London, see Matt Houlbrook’s Queer London. The organisers of Lady Malcolm’s Servants Balls were worried that their events were increasingly attracting individuals outside of the servant profession. People like Lady Austin clearly accessed multiple venues, suggesting the fluidity and success of these spaces.

The end of the party?

On a basic level, the police felt that it was not their role to regulate a charity event funded by the Malcolms. Policing outside the hall, to create order and regulate traffic, continued.

The last event was held in 1938. A key factor was the outbreak of the Second World War, but given the increasing challenges the ball posed, Lady Malcolm may have been relieved. The domestic industry and the era of the stately home was changing. Lady Malcolm’s Servants Balls captured a unique moment in time where London contained both pockets of queer social possibility and still fostered a significant domestic service industry.

The policing of public queerness is the reason we can learn about these past lives in our records. In their fancy dress, with rouged faces, these individuals were determined to create spaces to fully express their authentic selves. The decades since have seen many changes in LGBTQ+ culture, from the rise of drag shows to online apps. Though the context has changed immeasurably, the need to forge spaces continues.

Records featured in this article

-

- From our collection

- MEPO 2/3281

- Title

- Metropolitan Police file about treatment and supervision of Lady Malcolm's Servants Ball

- Date

- 1930–1938

-

- From our collection

- MEPO 2/3278

- Title

- Metropolitan Police file about treatment and supervision of Chelsea Arts Ball

- Date

- 1933–1939

-

- From our collection

- RG 14/546

- Title

- 1911 census entry for St Marylebone, where the Malcolm family lived

- Date

- 1911

-

- From our collection

- COPY 1/442/591

- Title

- Photograph of the Royal Albert Hall, Kensington, registered for copyright by William York

- Date

- 1899

Read more

Research Guide: Sexuality and gender identity history

This guide will help you find records relating to sexuality, including gay, lesbian and bisexual histories, as well as transgender and gender identity history.

Film: Queer Connections in the 1920s

What creative ways did people we might now consider to be LGBTQ+ use to meet and communicate with members of the same sex in the 1920s?

Blog: ‘Corrupting public morals?’ Fitzroy Square and queer desire

It’s December 1927. You travel to a basement flat near London’s West End. You are risking everything by being here. Undercover police are watching.

Blog: The Shim Sham Club: ‘London’s miniature Harlem’

Explore how queer club culture in the 1930s was vibrant and varied, especially in the growing post-First World War underground scene.