Important information

This story references domestic abuse.

Forming Chiswick Women’s Aid

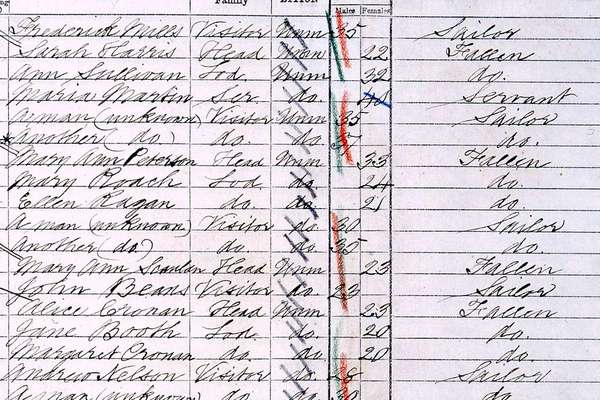

In February 1970, around 600 women travelled to Ruskin College in Oxford to attend Britain's first ever National Women's Liberation Conference. The event was organised in response to a period – the end of the 1960s – marked by the establishment and strengthening of movements demanding social, cultural and political change.

In Oxford, separate groups came together under the Women's Liberation Movement (WLM) and agreed on four demands: equal pay, equal educational and job opportunities, free contraception and abortion on demand, and free 24-hour nurseries. It has been described as the 'event that helped a generation find its voice.'

Despite shared demands, disagreements within subgroups of the Women's Liberation Movement weren't rare. In 1971, following questions around management and priorities of the Women's Liberation Workshop (a London-based section of the WLM), a handful of women left to form the Chiswick Women's Aid (CWA).

From the start, the group took an active role in the Chiswick area. They demonstrated against the government's proposed withdrawal of free milk for primary school children, highlighted essential food saving comparisons on blackboards on Chiswick High Street, and held town hall meetings on abortion legislation.

CWA were working in challenging times. Marital rape wasn't a crime, women needed a man's signature for bank loans, and women were not yet legally protected from discrimination on the grounds of sex or marital status.

At first, CWA meetings took place in people's homes, but it soon became clear an official centre was needed.

Establishing a centre

On the 3rd November 1971, after negotiations with Hounslow Council, Chiswick Women’s Aid was granted access to a building on 2 Belmont Road.

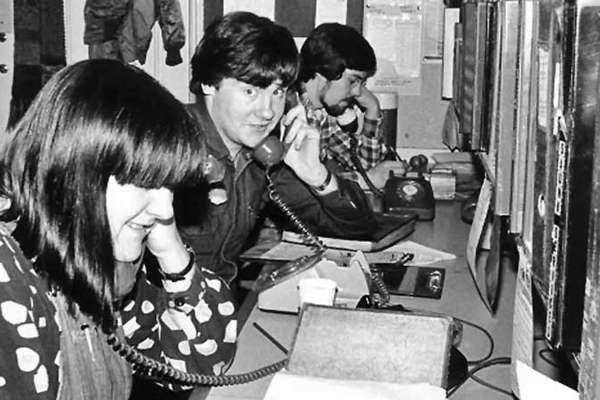

Work quickly began. CWA provided information on health, education and childcare issues, advised on legal matters, and also organised discussion groups, protests and sit-ins. They also helped women in their requests for financial support from the Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS).

They led feminist activities in Chiswick, attracting both women in need of support and those looking to support their work, often through volunteering. It was a place where women felt safe.

In the first month of opening the centre, a woman suffering violence at home arrived asking for shelter. Erin Pizzey, CWA's coordinator and spokesperson, didn't think twice. She quickly made arrangements to host the woman at the centre until her situation improved. Word spread and soon more women arrived seeking shelter.

And so, the Chiswick Women’s Aid refuge, the world's first refuge for women fleeing domestic violence, opened.

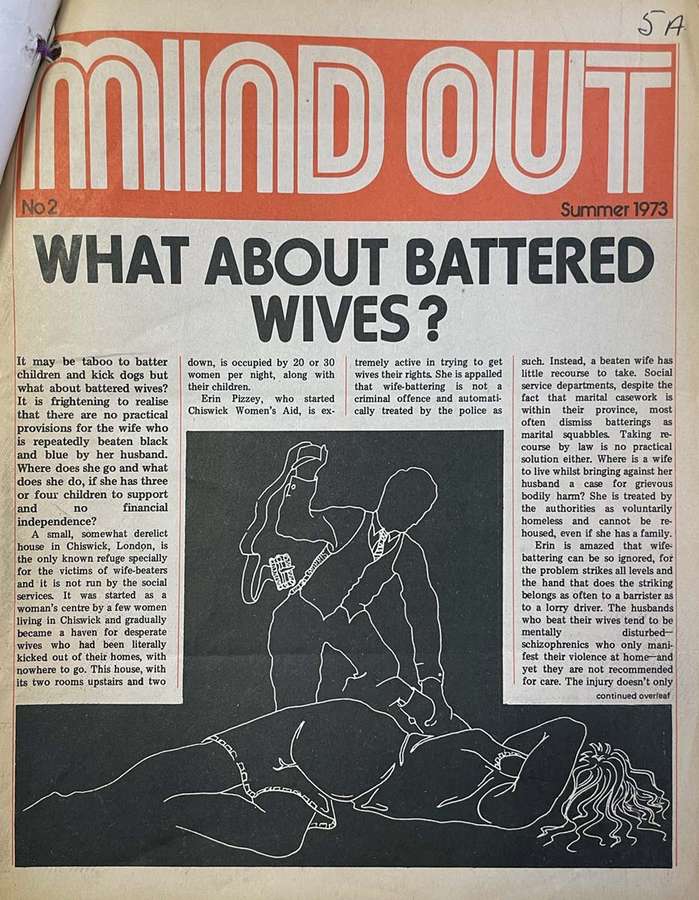

MIND OUT

WHAT ABOUT BATTERED WIVES?

It may be taboo to batter children and kick dogs but what about battered wives? It is frightening to realise that there are no practical provisions for the wife who is repeatedly beaten black and blue by her husband. Where does she go and what does she do, if she has three or four children to support and no financial independence?

A small somewhat derelict house in Chiswick London, is the only known refuge specially for the victims of wife-beaters and it is not run by the social services. It was started as a woman's centre by a few women living in Chiswick and gradually became a haven for desperate wives who had been literally kicked out of their home with nowhere to go. This house, with its two rooms upstairs and two down, is occupied by 20 or 30 women per night, along with their children.

Front cover of Mind Out magazine (no. 2, Summer 1973) reporting on 'battered wives', which was accepted terminology at the time. Catalogue reference: MH 154/837

New premises and continued action

The centre's situation changed in 1973. Hounslow Council's programme of regeneration included the property demolition of Belmont Terrace, and CWA received an eviction notice.

Fortunately, the Bovis Construction company, who already supported CWA with donations, stepped in to provide a new larger location: a 15-room, four-storey property, with a garden, on 369 Chiswick High Road. CWA moved in and applied to DHSS for exceptional grants.

Letters held at The National Archives and Pizzey's 2011 memoir The Way to the Revolution, show the relationship between Hounslow Council and the CWA was complicated. While the council tried to provide support, it also enforced compliance such as fire safety and household limits regardless of the exceptional circumstances the women faced. Making CWA's work more challenging, this tension led to public protest, which was widely documented in the media.

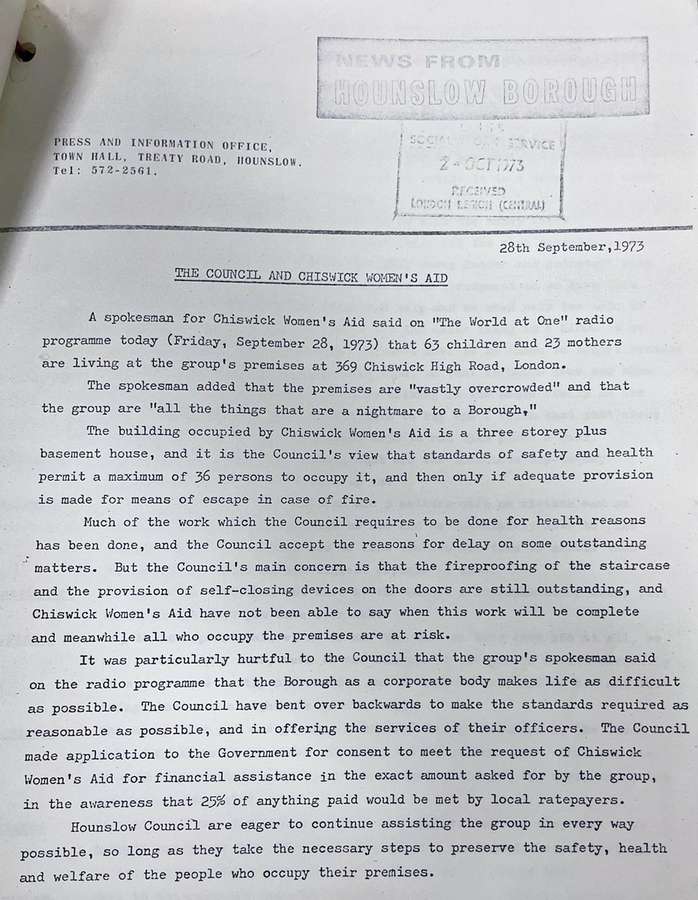

28 September, 1973

THE COUNCIL AND THE CHISWICK WOMEN'S AID

A spokesman for Chiswick Women's Aid said on "The World at One" radio programme today (Friday, September, 1973) that 63 children and 23 mothers are living at the group's premises at 369 Chiswick High Road, London.

The spokesman added that the premises are "vastly overcrowded" and that the group are "all the things that are a nightmare to a Borough."

The building occupied by the Chiswick Women's Aid is a three storey plus basement house, and it is the Council's view that standards of safety and health permit a maximum of 36 persons to occupy it, and then only if adequate provision is made for means of escape in case of fire.

Much of the work which the council requires to be done for health reasons has been done, and the Council accept the reasons for delay on some outstanding matters. But the Council's main concern is that the fireproofing of the staircase and the provision of self-closing devices on the doors are still outstanding, and Chiswick Women's Aid have not been able to say when this work will be complete and meanwhile all who occupy the premises are at risk.

It was particularly hurtful to the Council that the group's spokesman said on the radio programme that the Borough as a corporate body makes life as difficult as possible. The Council have bent over backwards to make the standards required as reasonable as possible, and in offering the services of their officers.

Press release of the article published on News from Hounslow Borough 28 September 1973. Catalogue reference: MH 154/837

CWA's report to government

In June 1973, CWA commissioned the Inter-Action Advisory Service to complete a report on the social problem of 'battered women' detailing the services they provided. 'Battered women' was an accepted terminology at the time, used by women themselves. The term domestic violence was first used in 1973.

CHISWICK WOMEN'S AID

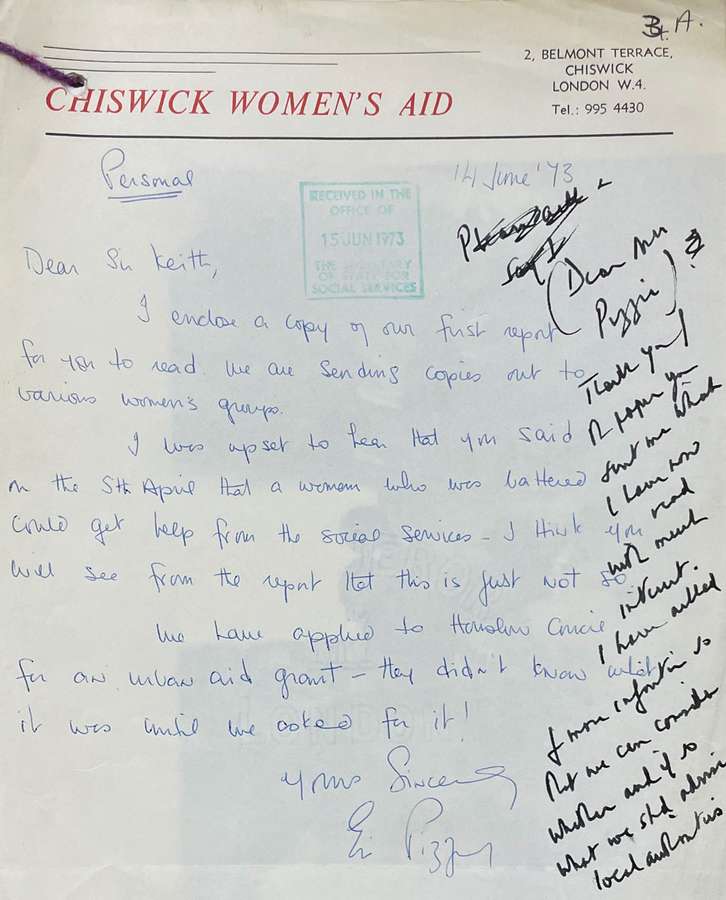

Dear Sir Keith,

I enclose a copy of our first report for you to read. We are sending copies out to various women's groups.

I was upset to hear that you said on the 5th April that a woman who was battered could get help from the social services – I think you will see from the report that this is just not so.

We have applied to Hounslow Council for an urban aid grant – they didn't know what it was until we asked for it!

Yours sincerely

E. Pizzey

Dear Ms Pizzey,

Thank you I [?] paper you sent me which I have now read with much interest. I have added [?] more information so that we can consider whether and if so what we should advise local authorities

Letter written by Mrs Erin Pizzey to the DHSS on 14 June 1973 enclosing the report. Catalogue reference: MH 154/837

The report was sent to the government's Department of Health and Social Security.

Now held at The National Archives, the report explained why and how CWA was set up, the services it provided – including accommodation and catering, childcare, psychological and legal aid – how it was financed, and how activities were collectively run on the principle of self-help.

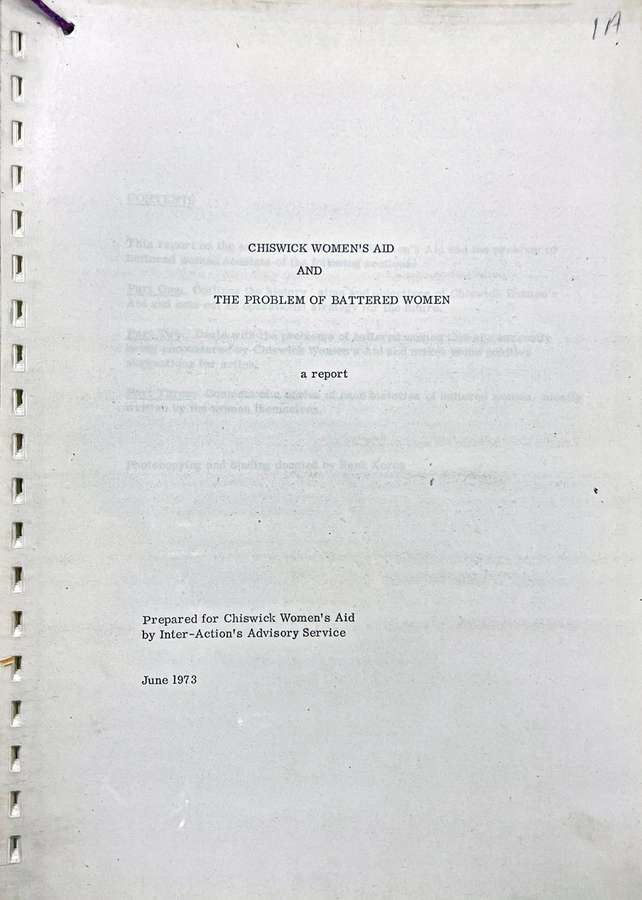

CHISWICK WOMEN'S AID

AND

THE PROBLEM OF BATTERED WOMEN

a report

Prepared for Chiswick Women's Aid by Inter-Action's Advisory Service

June 1973

The front cover for report prepared for Chiswick Women’s Aid by Inter-Action Advisory Service, June 1973. Catalogue reference: MH 154/837

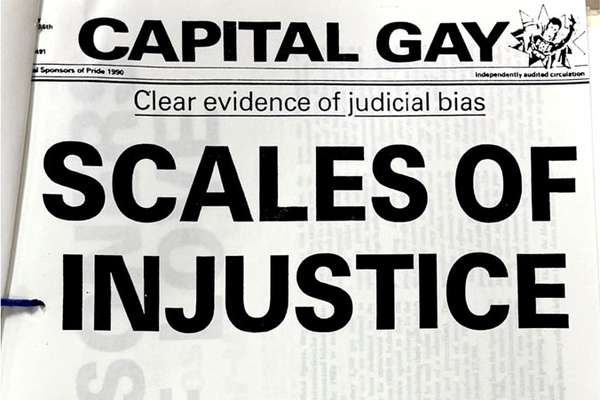

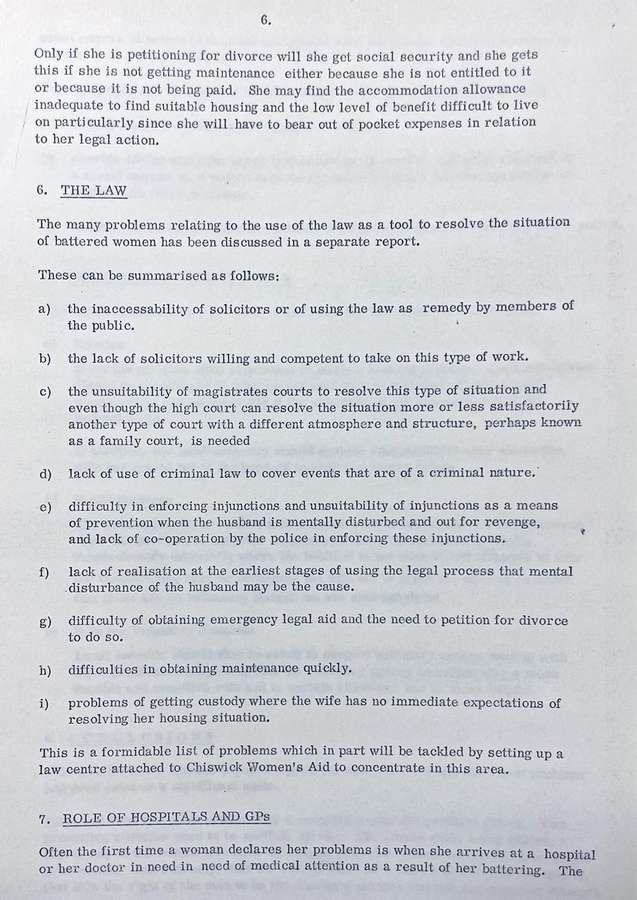

The report also underlined the lack of a legal framework to address domestic violence highlighting a shortfall of competent solicitors taking on cases, inappropriate and unsatisfactory laws, police not enforcing injunctions, and the inability to quickly obtain emergency legal aid and maintenance.

The report highlighted legal loopholes that made caring for and protecting women particularly complicated. These included the fact that married women leaving their husbands weren't allowed to claim social security payments until they filed for a divorce, which made alternative solutions to refuges hard to find.

6. THE LAW

The many problems relating to the use of the law as a tool to resolve the situation of battered women has been discussed in a separate report.

These can be summarised as follows:

a) the inaccessibility of solicitors or of using the law as remedy by members of the public.

b) the lack of solicitors willing and competent to take on this type of work.

c) The unsuitability of magistrates courts to resolve this type of situation and even though the high court can resolve the situation more or less satisfactorily another type of court with a different atmosphere and structure, perhaps known as a family court, is needed.

d) lack of use of criminal law to cover events that are of a criminal nature.

e) difficulty in enforcing injunctions and unsuitability of injunctions as a means of prevention when the husband is mentally disturbed and out for revenge, and lack of co-operation by the police in enforcing these injunctions.

f) lack of realisation at the earliest stages of using the legal process that mental disturbances of the husband may be the cause.

g) difficulty of obtaining emergency legal aid and the need to petition for divorce to do so.

h) difficulties in obtaining maintenance quickly.

i) problems of getting custody where the wife has no immediate expectations of resolving her housing situation.

This is a formidable list of problems which in part will be tackled by setting up a law centre attached to Chiswick Women's Aid to concentrate in this area.

Report Chiswick Women’s and The Problem of Battered Women part II, page 4. Catalogue reference: MH 154/837

The report concluded with a list of immediate recommended changes:

- 'extension of self-help centres or refuges where battered women and their children can come

- resources being made more quickly available by local authorities to do this

- a greater understanding and awareness of the problem

- changes in the law, its enforcement and its practice

- changes in social benefit and housing provisions

- tenancy or ownership of the marital home being jointly held by husband and wife

- a recognition of the criminality of inflicting severe physical violence of one’s marital partner'

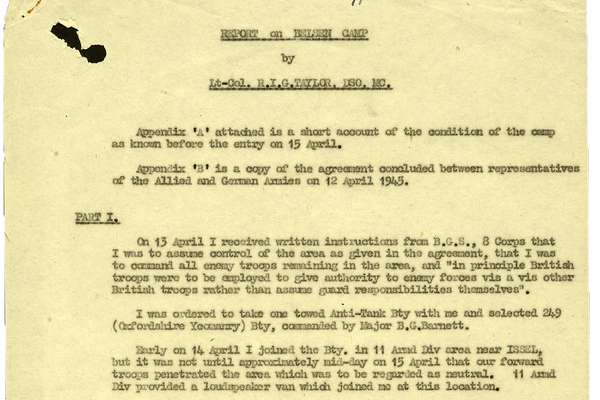

Government action

The report, the increase of refuges across the country, and media attention fuelled by Erin Pizzey's 1974 book Scream Quietly or the Neighbours Will Hear – now considered one the first books on domestic violence – as well as Michael Whyte's documentary of the same name, led to greater awareness of the issue. In response, the government established a Select Committee on Violence in Marriage and held a parliamentary inquiry in 1974 to 1975.

The Select Committee's report was published in 1976 and immediately circulated to local authorities. It stated, among other things, that for any government tackling domestic violence the provision of national refuges had to be the priority. It said there should be a minimum of one family refuge space per 10,000 people in the population.

This was soon followed by the 1976 Domestic Violence and Matrimonial Proceedings Act, which amended the 1967 Matrimonial Homes Act. The act provided police with powers of arrest for the breach of injunction in cases of domestic violence.

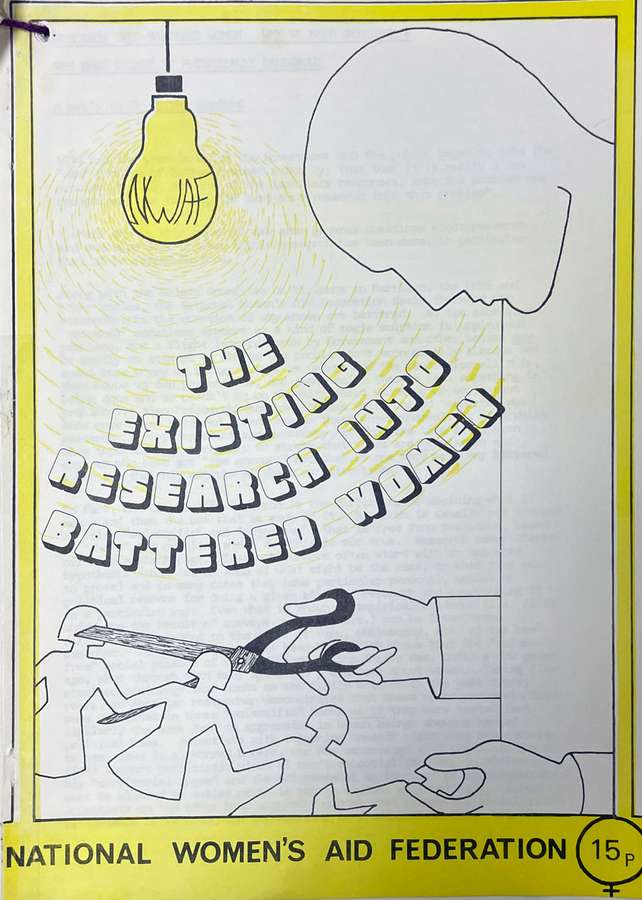

Leaflet produced by the National Women’s Aid Federation detailing existing research into battered women. Catalogue reference: MH154/835

National Women’s Aid Federation

By 1974, as things finally started to move at government level, change also came at grassroots level, particularly in Chiswick.

Most UK refuges coalesced into the National Women's Aid Federation (NWAF), established in 1974. However, following disagreements between NWAF and Erin Pizzey, Chiswick Women’s Aid remained independent.

This independence made it harder for CWA to request exceptional grants for their pioneering work. From 1976, following the creation of NWAF, the DHSS decided to phase out the exceptional support provided to CWA. Instead it requested they applied for Urban Aid Grants – a 1968 setup scheme providing extra help in areas where existing services were under strain, as other refuges were expected to do.

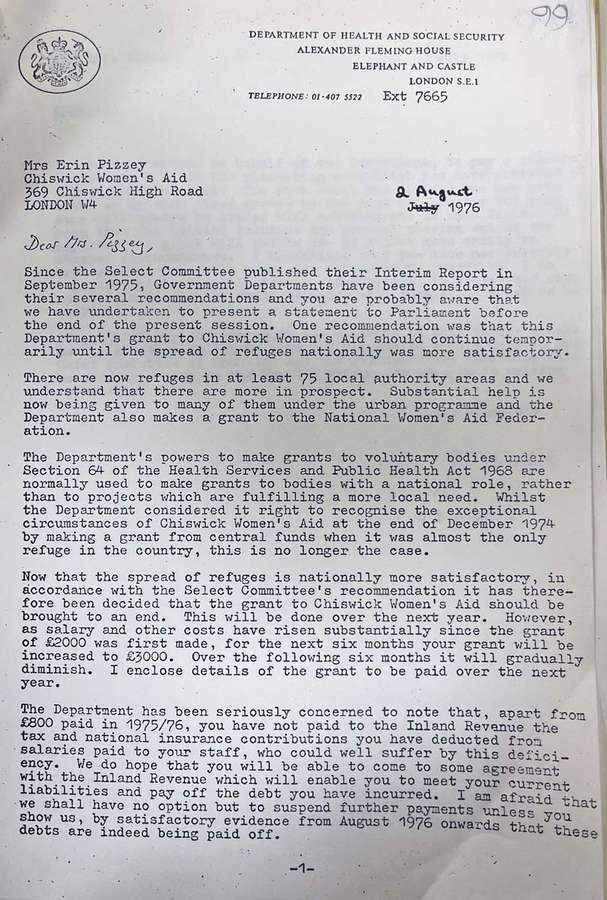

The letter from DHSS to CWA stated:

Whilst the Department considered it right to recognise the exceptional circumstances of Chiswick Women’s Aid at the end of 1974 by making a grant from central funds when it was almost the only refuge in the country, this is no longer the case.

Now that the spread of refuges is nationally more satisfactory, in accordance with the Select Committee’s recommendation it has therefore been decided that the grant to Chiswick Women’s Aid should be brought to an end.

MH 154/837

2 August 1976

Dear Mrs Pizzey

Since the Select Committee published their Interim Report in September 1975, Government Departments have been considering their several recommendations and you are probably aware that we have undertaken to present a statement to Parliament before the end of the present session. One recommendation was that this Department's grant to Chiswick Women's Aid should continue temporarily until the spread of refuges nationally was more satisfactory.

There are now refuges in at least 75 local authority areas and we understand that there are more in prospect. Substantial help is now being given to many of them under the urban programme and the Department also makes a grant to the National Women's Aid Federation.

The Department's powers to make grants to voluntary bodies under Section 64 of the Health Services and Public Health Act 1968 are normally used to make grants to bodies with a national role, rather than to projects which are fulfilling a more local need. Whist the Department considered it right to recognise the exceptional circumstances of Chiswick Women's Aid at the end of December 1974 by making a grant from central funds when it was almost the only refuge in the country, this is no longer the case.

Now that the spread of refuges is nationally more satisfactory, in accordance with the Select Committee's recommendation it has therefore been decided that the grant to Chiswick Women's Aid should be brought to an end. This will be done over the next year

Letter sent to Erin Pizzey by the DHSS to inform phasing out of current grants. Catalogue reference: MH 154/837

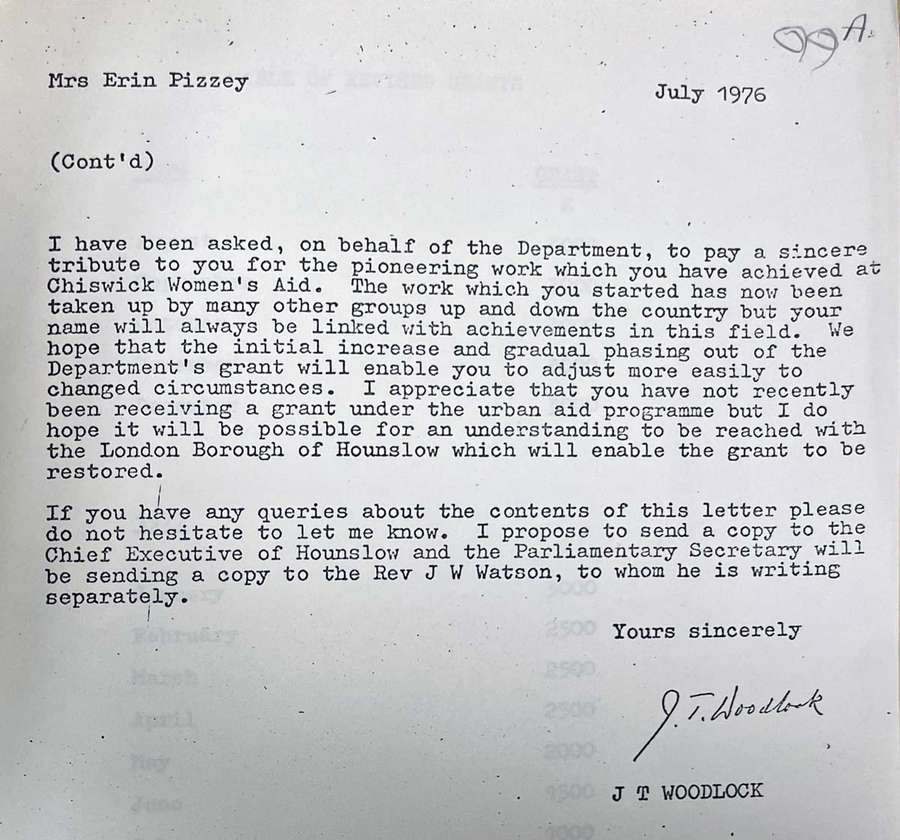

The letter outlining the end of the exceptional funding finished on a bittersweet note:

'I have been asked, on behalf of the Department, to pay a sincere tribute to you for the pioneering work which you have achieved at Chiswick Women’s Aid. The work which you started has now been taken up by many groups up and down the country but your name will always be linked with achievements in this field.'

Mrs Erin Pizzey

(Cont'd)

I have been asked, on behalf of the Department, to pay a sincere tribute to you for the pioneering work which you have achieved at Chiswick Women's Aid. The work which you started has now been taken up by many other groups up and down the country but your name will always be linked with achievements in this field. We hope that the initial increase and gradual phasing out of the Department's grant will enable you to adjust more easily to changed circumstances. I appreciate that you have not recently been receiving a grant under the urban aid programme but I do hope it will be possible for an understanding to be reached with the London Borough of Hounslow which will enable the grant to be restored.

If you have any queries about the contents of this letter please do not hesitate to let me know. I propose to send a copy to the Chief Executive of Hounslow and the Parliamentary Secretary will be sending a copy to the Rev J W Watson, to whom he is writing separately.

Yours sincerely,

J T Woodlock

Second page of the letter sent to Erin Pizzey by the DHSS to inform phasing out of current grants. Catalogue reference: MH 154/837

The end of the funding

The ending of the exceptional funding brought further tensions between CWA, DHSS and Hounslow Council and a continuous struggle to find and grant funding to run the centre. Yet, the work continued amid the battles.

Erin Pizzey worked at CWA until 1983, when she parted following disagreements with other members. When she left, the centre changed its name to Chiswick Family Rescue, until it was renamed Refuge in 1993. Today, Pizzey is considered a men's rights activist and her views on domestic violence are at odds with many abuse charities. She received a CBE in 2024 for services to victims of domestic abuse.

The NWAF ran as a national federation until 1978, when it split into regional units to guarantee more autonomy: Women’s Aid Federation Northern Ireland; Welsh Women’s Aid; and the Women’s Aid Federation of England.

In 2020, there were 261 refuge services in the UK, a stark contrast to 1971, when Chiswick Women's Aid's 2 Belmont Road centre opened its doors for the first time.

Find out how to get help if you or someone you know is a victim of domestic abuse on gov.uk.

Records featured in this article

-

- From our collection

- MH 154/837

- Title

- Chiswick Women's Aid: Minutes and notes of various meetings

- Date

- 1973 – 1974

-

- From our collection

- MH 154/835

- Title

- Research on marital violence: proposals, discussions, papers, comments and correspondence

- Date

- 1976 – 1978

Read more

Blog: Researching the birth of the first domestic violence refuge

Read more about Giorgia's research into 'How the first women's refuge enacted change in the UK' and how it led to a moving personal encounter.