Record revealed

'Fallen' women of the real Albert Square

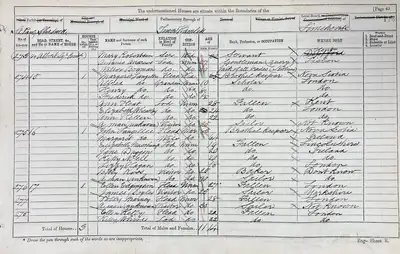

Just off a busy road in London's East End is Albert Gardens, previously called Albert Square – the well-known fictional location of the soap opera EastEnders. Thanks to the 1871 Census we can meet the real residents here, who give a curious insight into 19th-century London life.

Images

Image 1 of 2

Page 43 from the 1871 Census.

Partial transcript

NAME and Surname of each Person

Ann Heat

AGE of Male/Female

Female, 28

Rank, Profession, or OCCUPATION

Fallen

WHERE BORN

Kent

NAME and Surname of each Person

A man (unkown)

RELATION to head of family

Visitor

Age of Male/Female

Male 25

Rank, Profession, or OCCUPATION

Sailor

WHERE BORN

Not known

Image 2 of 2

Page 40 from the 1871 Census.

Why this record matters

- Date

- 1871

- Catalogue reference

- RG 10/544

Located off Commercial Road near Limehouse, London, is a square of three-storey terraced houses enclosed around a garden. Today it's called Albert Gardens, but it was once known as Albert Square, as it's listed in the 1871 Census held at The National Archives.

The households listed in the census tell us a lot about this 1870s East End London community. They were not typical family households. Each held a significant number of lodgers and visitors. These were the residences of some of London's many sex workers.

The employment for most of the women living at Albert Square was listed as 'fallen', a biblical reference to the fall of Eve referencing perceived moral failings and a 'fall' in public reputation. The fluid term could refer to everything from a full-time sex worker, to a woman having sex outside marriage. They are listed here alongside 'heads' of households described as 'brothel keepers'.

Most male ‘visitors’ are listed as ‘sailors’, a stark contrast to the moralistic label given to the women. Along the road from Albert Square were the London Docks in Shadwell, which brought people to the city for periods away from home and family life. Sailors were known to frequent sex workers, who gravitated towards ports and docks across England for the trade it provided. The sailors listed were from a variety of places, including Germany, London, Ireland, Exeter, Nova Scotia.

The fleeting nature of the interactions meant details could be inaccurate or sparsely captured. Here there is a useful note from the enumerator – a person employed in taking a census – speaking in an unusually informal tone of voice for a census: ‘These fallen women very often don’t know either the names or the ages of those men who sleep with them, their ages can therefore only be guessed at.’ This is illustrated by the missing names of some of the sailors, with the remark 'A man (unknown)' in the name column.

As 'brothelkeeper' was not on the Registrar General’s official list of recognised professions, it remains unknown if the profession was declared or assumed by the enumerator. Given the surviving records are the enumerator's copies, rather than the household schedules, it's unlikely the residents knew the final details recorded.

Sex work itself was not directly criminalised, but many surrounding elements were, such as soliciting. The average sex worker tended to be less visible on census returns, not declaring their work honestly, due to risk or judgement. It’s more common to find sex workers referenced in institutions like asylums and prisons, or on police returns for homeless persons when soliciting the streets.

Women often opted in and out of sex work as necessary – particularly in areas facing extreme poverty found in London's East End – finding other seasonal or intermittent employment. This census was taken on the night of 2 April 1871. Had it been another day, some of the women's listed trades may have been different. But doubtless, if it was not these individual sex workers and sailors recorded on that night in Albert Square, it would have been others.