Background

Emmeline Pankhurst was the leader of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), one of the predominant suffrage organisations involved in campaigning for votes for women. She interacted constantly with the government, which leaves us with a wealth of records around her involvement in the movement for women’s suffrage.

Emmeline Pankhurst, 1908. Catalogue reference: COPY 1/526 46322.

Our records contain everything from prison petitions in Emmeline’s own words asking for suffragettes to be treated as political prisoners, as well as items seized from WSPU headquarters. They provide fascinating insights into her activities and life.

Votes for women

The Women’s Social and Political Union

The WSPU had been founded in 1903 in Manchester, determined to try to get votes for women by any means necessary. Founded by Emmeline and her daughters, the organisation was frustrated by the many prior decades of slow progress and disappointments. The WSPU was known for its militant actions: its members became known as ‘suffragettes’ – a Daily Mail slur that was reclaimed by the movement. The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was the predominant constitutional organisation, often known as the ‘suffragists’.

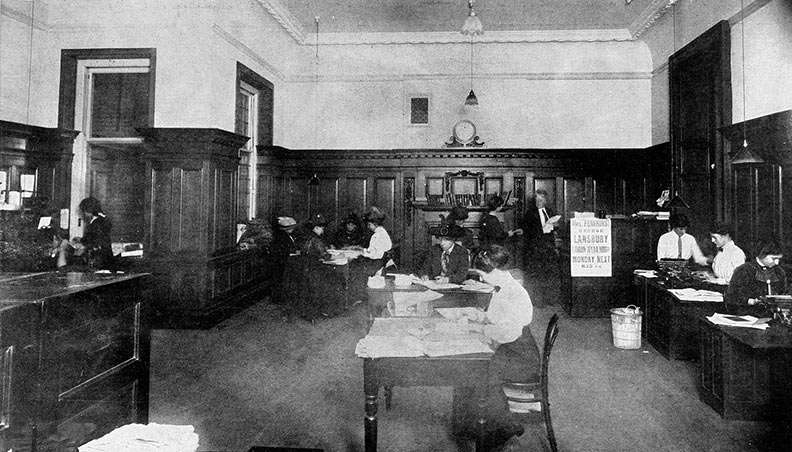

The general office at the WSPU headquarters, Lincoln’s Inn House, Kingsway. As seen in the Illustrated London News. Catalogue reference: ZPER 34/142.

Emmeline was not a flawless character; along with daughter Christabel, she had a reputation for being authoritarian. Under her leadership the WSPU was highly organised; from its headquarters in central London it communicated with regional branches, organised militant campaigns and reached out to members. The state closely monitored activities at the headquarters, keeping a particularly close watch on Emmeline.

‘Deeds, not words’

The WSPU’s policy of direct action had begun in 1905, when Christabel Pankhurst, daughter of Emmeline, and Annie Kenney interrupted a meeting to ask politicians whether they were in favour of votes for women. In the following years the methods and tactics developed, often organically, as the women repeatedly felt their voices were not being listened to. Emmeline herself was arrested, and evaded capture, many times for the cause.

‘For nearly 50 years we had your sympathy and your support, and nothing happened ... Nothing can stop militancy now, and it is going on until we get the vote. We tried by constitutional ways to get you to give us the vote, but you did not do it. What can we do now but carry on this fight ourselves? And I want you, not to see these as isolated acts of hysterical women, but to see that it is being carried out on a plan and that it is being carried out with a definite intention and a purpose. It can only be stopped in one way: that is by giving us the vote.’

Emmeline Pankhurst speaking at Hampstead Town Hall, 14 February 1913, as recorded in a police report

Record revealed

List of suffragettes arrested from 1906–1914

More than a thousand people who supported women’s right to vote were arrested for their activism. This document records them – and includes some famous names.

As the movement continued, mass window smashing campaigns and the targeting of MPs’ houses became more common forms of protest for the WSPU.

You can follow the increasingly militant actions of the suffragettes through some of our other blog posts. Militant methods were often divisive. While historians disagree about their effectiveness, our records show the huge impact militant actions had across government.

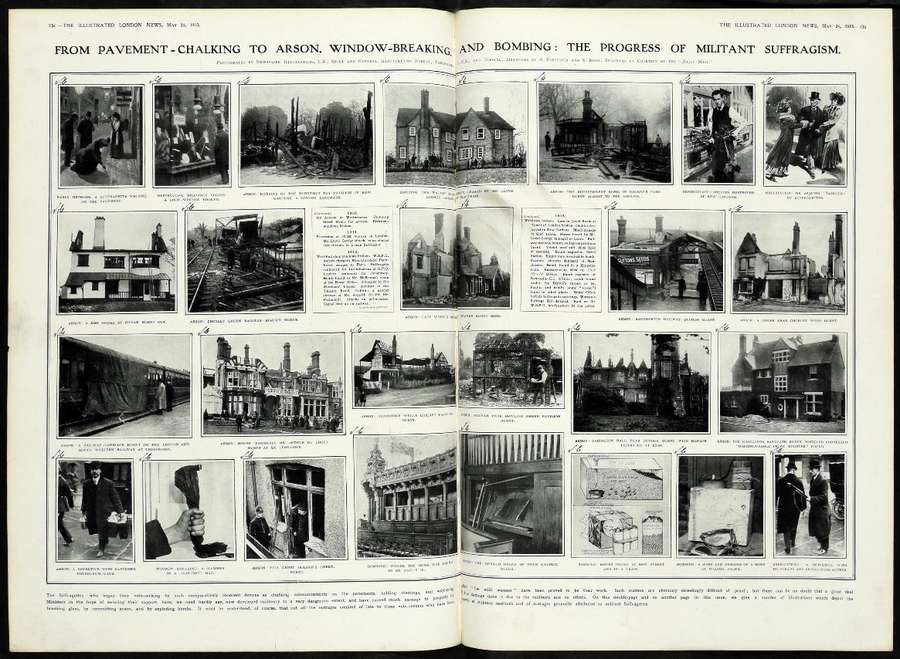

Extract from The Illustrated London News © ‘From pavement-chalking to arson, window-breaking and bombing: the progress of Militant Suffragism’, 24 May 1913. Catalogue reference: ZPER 34/142.

Listen

Listen: Suffrage 100: Did militancy help or hinder the fight for the franchise?

By 1912, militancy associated with the Suffragette movement hit its peak, with regular arson attacks, window-smashing campaigns and targeting of MPs’ houses. In retrospect, these tactics are often what the movement is famed for. In this talk Dr Fern Riddell and Professor Christa Calman ask: did these tactics help or hinder the cause?

Audio transcript for "Listen: Suffrage 100: Did militancy help or hinder the fight for the franchise?"

This talk is called “Suffrage 100 – Did militancy help or hinder the fight for the franchise?”.

It was presented by Dr Fern Riddell and Professor Christa Calman. It was recorded on the 20th February 2018 at the National Archives, Kew.

We now have Fern Riddell. Fern specialises in sex, suffrage and culture in the Victorian and Edwardian eras and her research focuses on Kitty Marion. She has a very exciting book out in April I believe, Death in Ten Minutes, so do look out for that.

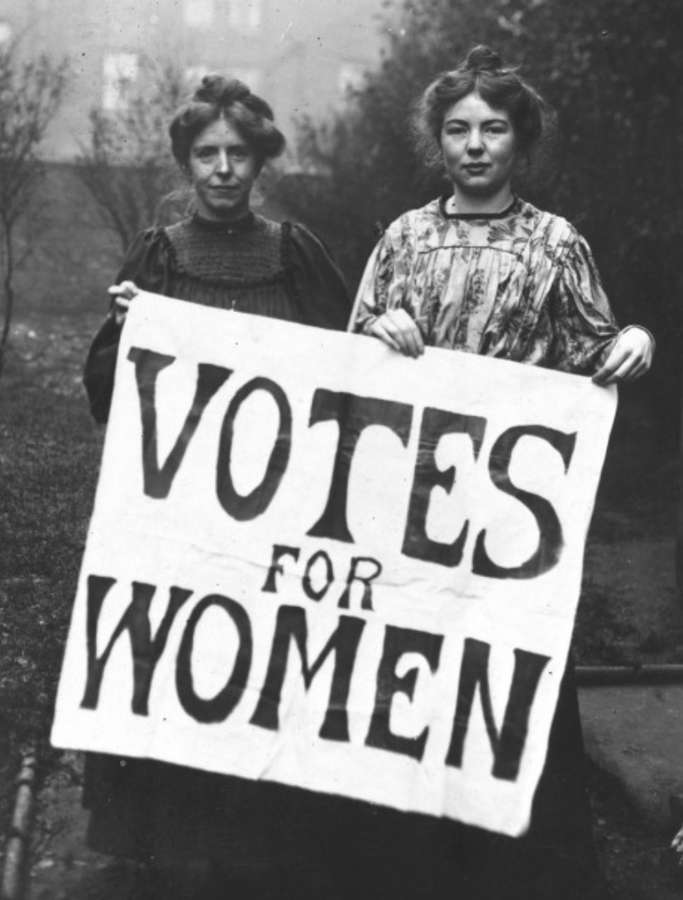

This is the image we mostly have of the Suffrage movement. The image of Emmeline Pankhurst standing talking, convincing people to listen to her. Or it’s this image, young women caught between the forces of state and often victimised by what happens to them.

But for me, being really the only historian that we have working on the nationwide scope and scale of the arson and bombing campaign, this is the image for me of the suffragettes. And tonight I want to talk very quickly about the reality of militancy. Because one of the issues that I have whenever we have debates like this, we’re often asked, did militancy help or hinder, when actually we have no understanding of what the reality of militancy was.

That research has never been done in our history, really until the last 10 years. And that might seem incredible if you think that we’ve had a 100 years to talk and record and learn about the women’s movement and learn about the suffragettes, and yet this has been something that has been continually hushed up. People talk about the fact that we shouldn’t talk about this part of our history, that somehow it demonises or condemns the Suffragette movement; personally for me, as a young suffrage historian, what I have found when we go back into the archives and look at the reality of these attacks, is that we come across the most incredible voices of women – who have been lost to our time and lost to history, and who deserve to have a place in our history and in our understanding of the Suffrage movement, as much as the leaders and as much as the suffragists.

Christabel Pankhurst wrote that “If men use explosives and bombs for their own purpose, they call it war, and that the throwing of a bomb that destroys other people is then described as a glorious and heroic deed. Why should a woman not make use of the same weapons as men? It is not only war we have declared, we are fighting a revolution”.

And I think that’s one of the most important things to bear in mind, when we’re talking about militancy. The women of the WSPU did not think that they were simply an organisation who were taking on and doing things that women did not do in the past, they were at war. And like all soldiers, they resorted to violent methods.

This is the arson attack on the house of Arthur Ducrow who was an MP for Hastings, and this was led by Kitty Marion whose incredible autobiography, which has never been published before, I have been lucky enough to spend the last seven years working on, and as Kitty said, Death in Ten Minutes, which is the first publication of the story of her life, comes out in April.

This is the inside and what I would really like you to do, when you see the image of this, is take on the scope and scale of what these arson attacks were resulting in, because from really 1912 to 1914 we see the most incredible campaign of bombing and arson attacks that we’ve never talked about.

In one month alone in May 1913 there are 52 attacks, both arson and bombings, and one of the difficulties is that we don’t actually understand how many of those were bombs, or how many of those were simply arson attacks, because many of the arson attacks were started by incendiary devices. That means that people planted bombs that were going to explode later.

Here we have a bomb attack at Oxstead, the arson attack at Kew and the attack on the church of St Catherine’s in Hatcham. This for me is so important, to understand that the women of the WSPU felt that they had no other recourse to convince the government to listen to them. They decided to leave incendiary devices, as Elizabeth said, in churches, in trains, on commuter trains, burn down MPs’ houses, to attack and take out communications from telegraph and telephone wires between London and Glasgow. Imagine taking out the internet or phone lines between London and Glasgow today. We have a word for it: we understand this as domestic terrorism and the suffragettes themselves were intensely proud of their ability to terrorise both the general public and the government and the state itself.

Often when the suffragettes would print reports of these attacks by its members they would come underneath headlines such as “Reign of Terror”. They weren’t shy about the impact that it was having on the public. And as you can see, it was always a spectator event, people had to come to see what was happening.

No one was free from a suffragette attack and one of the things that I always think about is, if you think wherever you could find a woman, you would be able to find a suffragette bomb at this time.

Often much like the IRA used to leave notes or would call in the fact that they had a bomb in place, the suffragettes would leave suffragette posters, memorabilia, ephemera; they would write and leave pamphlets at the site of any of their attacks, like this one at Plymouth Hoe, which had “Votes for Women, Death in Ten minutes”, inscribed on it. You might think that that meant that they didn’t think that the bomb would go off and that it would be found and it wouldn’t be dangerous, but for those who think that the suffragettes weren’t fully aware of the damage a bomb could do, remember that these were timed devices; they might leave it there in an empty house at 1am but they had no way of knowing that in the three hours it would take for it to go off, that someone wouldn’t come in and possibly be in danger, so the threat of violence and the threat of danger was very real.

The chemical attacks that the suffragettes led, which included sending a powder that would irritate the eyes, nose and throat, in the post, or in one famous occasion actually going to Asquith and attempting to throw it in his face at a general meeting. These attacks were supposed to cause damage, they were supposed to cause irritation and for many of the postmen who actually took out the vials of phosphorous that were being sent in the post, to MPs, those broke and on contact with air would burst into flames, leaving postmen with severe burns. So there were a number of casualties in this campaign that we never really talk about. Academics may discuss it between each other but it’s a memory that hasn’t impacted on our cultural understanding and our public memory of the suffragettes.

So does militancy help or hinder? For me I think it does both; we know that the wider public found the militancy to be uncomfortable, annoying, difficult, dangerous, scary or worrisome; you only have to look at today when we see the visual impact of attacks or fires on trains; as many of you I’m sure saw in the last couple of weeks, there was a fire on a train very near to here and the fear that it causes straight away, I think it would be almost ridiculous to assume that a fire on a commuter train in the 1910s would cause anything less than the same instant worry and impact that it does now.

So as far the public were concerned I think the WSPU’s militancy was dangerous, but as far as the government were concerned there was a very different pressure. At the end of World War One there was a serious fear that the militancy would kick off again and the government, attempting to put the state together in the aftermath of the social and economic destruction that came with World War One, desperately needed to make sure that the world that they were trying to put back together would remain as calm and as careful as possible.

And I personally believe that’s one of the reasons why Franchise was granted, specifically to women over the age of 30 who owned property, many of whom or at least some had an engagement with property, many of whom were in the WSPU, we could see at that time. So whenever you think about militancy, bear in mind the scale of this campaign that was from Scotland all the way down to Cornwall, throughout London and across to Ireland, these attacks were taking place.

Thank you very much Fern.

So finally we have Christa Calmann, Professor of History at Lincoln University, who has done lots of research on the Women’s Social and Political Union, including her book called Women of the Right Spirit. And so over to you Christa.

I guess the problem with going third is that most of the good quotations have already gone, but for some, maybe repetition may be a good thing. I think what I’m hoping to go for is probably somewhere a little bit in the middle ground really, which is picking up on some of the points that Elizabeth made but also picking up on some of the points that Fern made, and although I am the last speaker I do want to go back to this question of definitions.

So in terms of the, well actually the first one doesn’t even overlap, when you go back and look at what the suffragettes themselves meant by militancy at the time, which I think is probably as good a way of approaching the topic of suffragette militancy as any, let’s actually see what they thought they meant by being militant.

The very first act of militancy that we see defined and described by such was actually in February 1904, when Christabel Pankhurst went to hear Winston Churchill speak at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, and she had been fortunate enough to secure a platform ticket for this event, which meant that it was a very prestigious place to sit. And at the end of Churchill’s speech, she attempted, uninvited, to put an amendment to the resolution that he was about to put to the meeting. Political meetings in those days were very, very set piece events and would generally end with the passing of a resolution, and of course you have a sympathetic crowd and some people would be coming along to have a go and you have other people coming along and you are very much preaching to the converted.

So Churchill is moving this resolution and Christabel gets up to try and put an amendment to the resolution and she says afterwards, I think it’s quite interesting that she says this in her autobiography which she writes in the 1940s, so that by the time that she writes her autobiography, the events that Fern described so graphically happened. Christabel has been to prison several times, she has seen many of her friends and many members of her family forcibly fed, she’s seen women be seriously injured in the result of this suffragette struggle, but she says looking back on it, that this was the first militant step – it was the hardest to do in front of the great and the good of Manchester, in front of Manchester society.

The second definition we have, and I won’t go into great detail as it’s the one that Elizabeth read out to us, is Emmeline’s description of her meeting in May 1905 when she has this impromptu meeting outside parliament after the Suffrage Bill has yet again been talked out.

And then the third one, perhaps better known, is the 13th of October 1905, Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, where they stand up and shout “Votes for women, will the Liberal government give votes for women?”. They are bundled out of the hall by stewards, and then there are various descriptions of whether Christabel actually spits at a policeman or whether she spits and hits. Some newspaper descriptions at the trial state that she strikes him as well. This is the day which is celebrated ever afterwards as Prisoners’ Day.

Now the point I want to make about this, is that the militancy of these particular actions lies not so much in the behaviour itself but in the gender of those who are engaging in this behaviour, and it is no coincidence that the women who carry out these acts are all schooled in radical socialist politics and they are used to the politics of the street corner. They are used to a robust form of politicking and they are used to this sort of very, very direct political behaviour.

In fact one thing that most people do tend to forget is that Emmeline Pankhurst’s first arrest was nothing to do with Suffrage agitation. It was in the 1890s. It was a demonstration for the rights of socialists to speak in public in Manchester parks, and that was the first time she was arrested.

So they are schooled in this tradition of radical militant street politics and street corner politics. And these acts are seen as militant and seen as inappropriate when women carried them out. Fern gave us the quotation from Christabel about men can do this and are lauded and women do this and it’s seen as inappropriate, as peculiar, as deviant, and these sorts of comparisons go all the way through the suffragette campaign, all the way from the beginning.

It is a coincidence, because of where the Free Trade Hall happens to be built, but there is no coincidence that they really milk the fact that the Free Trade Hall, the site of the first suffragette arrests, is of course built on the site of the Peterloo Massacre, and this is frequently referred to in speeches both by Annie and Christabel themselves and also by other women saying, you know, but the first time women were arrested in this struggle, for the first time, standing on the ground where our forefathers were killed for demanding their political rights. So they draw on this radical heritage all the way through.

The second point I want to make in my remaining three or four minutes is that it’s a real error to think about militancy as being a scale of actions in which one action replaces another and this is not to run away from what Fern was talking about, by any means, but I think it is also worth remembering that while a number of women in the campaign were carrying out arson attacks and bomb attacks, and the precursor to this, if you like, which was the large-scale mass window smashing which becomes a tactic from round about 1910. The first window smashing is 1908 and interestingly, and this is one quotation that I thought you might use, but didn’t, interestingly, when Mary Leigh and Edith New are charged with this, in court Mary says “well it was windows this time but it will be bombs next time”, although it takes a good five years for this to actually come up.

But while these other tactics are going on, different militant tactics are still being practiced – not just the heckling, not just the demonstrating but at the same time that they are evolving, if you like, or adopting bombing and arson. Suffragettes are also adopting other forms of militancy on a really widespread scale, so it’s not until about 1913 that the theatre protests kick off and it’s not until 1913, that they start an initiative called Prayers for Prisoners. And the really interesting thing about Prayers for Prisoners is it involves women going to church services, generally Anglican but sometimes Catholic sometimes Free churches; they are not wild protests, they are not rowdy protests, but in the bits of the liturgy where you are supposed to remain silent, women get up and say “God save Mrs Pankhurst, God save Rachel Pearce, God save Lillian Lenton, God save all these women who are hunger striking in prison”.

As a neat little aside, it was almost a century to the day that suffragettes were physically thrown out of York Minster for saying “God save Mrs Pankhurst, God bless Rachel Pearce, God save all the brave women who were starving in prison and were fighting for the vote”; they were picked up literally by the stewards, and thrown out, almost a century to the day that the first women Bishops were consecrated in York Minster.

And that would be my final point, that these inappropriate, transgressive behaviours, don’t just have an impact on public opinion, they also have an impact on the perpetrators.

Elizabeth gave us another definition of militancy, which she said is using confrontational or violent tactics in the pursuit of a political or social cause. And I think it’s the social aspect of suffrage that we often overlook when we think about militancy, although suffrage historians are always very keen to say the suffrage campaign wasn’t just about the vote;, it was about changing attitudes to women, it was about changing social attitudes, and I think it’s also about women changing themselves and empowering themselves, through different behaviours. So I think if you take a broader definition of militancy and look more broadly at its impacts, then it makes you come up with a different variety of answers to the question.

So thank you very much to our panellists, Fern, Christa and Elizabeth. Can you give them a round of applause please?

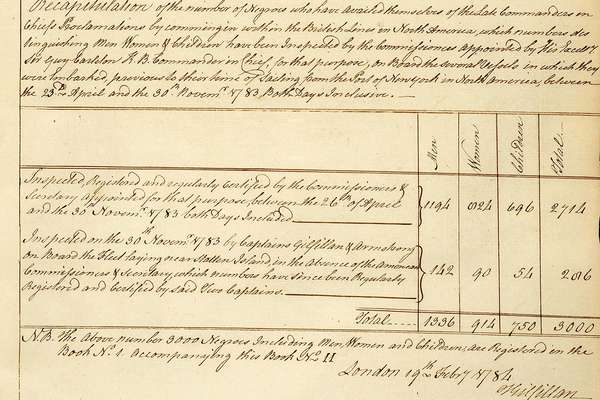

Foot soldiers of the movement

While it is great to celebrate figureheads, such as the Pankhursts, the strength of the suffrage movement lay in the foot soldiers who were willing to fight alongside them. The Home Office Amnesty from 1914 records 1,224 women and 108 men who were imprisoned between 1906 and 1914 for offences committed for the votes for women campaign.

These numbers only reflect those arrested, not the people who avoided arrest or campaigned constitutionally; they represent the tip of the iceberg of the movement and the records we hold.

This was clearly a national, mass, organised movement.

Suffragettes Annie Kenny and Christabel Pankhurst 1906. Catalogue reference: COPY 1/494.

The Representation of the People Act

At the outbreak of war, Emmeline paused the militant movement, and instead worked with the government to support the war effort. Many suffrage supporters took up roles on the home front or travelled abroad to support the war.

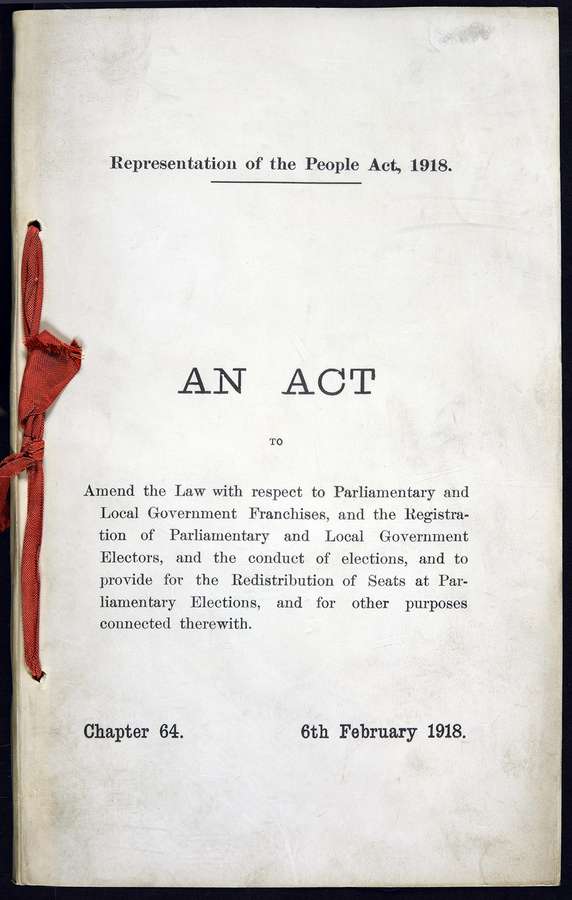

Eventually, after decades of peaceful and militant campaigns, on 6 February 1918, the Representation of the People Act (1918) received Royal Assent and came into force. This act provided some women with a vote in Parliamentary elections for the first time.

Representation of the People Act, 1918.

AN ACT

TO

Amend the law with respect to Parliamentary and Local Government Franchises, and the Registration of Parliamentary and Local Government Electors, and the conduct of elections, and to provide for the Redistribution of Seats at Parliamentary Elections, and for other purposes connected therewith.

Chapter 64. 6th February 1918.

Representation of the People Act, 1918. Catalogue reference: C 65/6385.

-

- From our collection

- C 65/6385

- Title

- Representation of the People Act, 1918

- Date

- 1918

Ten years later in July 1928, the Conservative government’s Representation of the People Act (1928) finally extended the vote to all women over 21 years of age. Emmeline had died just weeks before this, on Thursday 14 June 1928. Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS, was still alive and attended the parliamentary session to see the vote take place.

Emmeline was commemorated two years later with a statue in London’s Victoria Tower Gardens, on which we also hold records. It was unveiled in 1930 by the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, who had opposed votes for women.

Read more

Blog: ‘Raided!!’ London headquarters of the Women’s Social and Political Union

This blog post shows how the headquarters of the WSPU were constantly vulnerable to police raids.

Blog: Keeping tabs on suffragettes: the official watchlist

What can we learn from the official watchlist of suffragettes, which contains details of over 1,300 arrests?

Blog: The Archivists’ Guide to Film: Suffragette

In this post from our series in which staff at The National Archives write about favourite films, Katie Fox and Liz Fulton discuss Suffragette (2015)

Research Guide: How to look for records of women’s suffrage

This guide will help you to find records of the women’s suffrage movement and of the women and men who campaigned for the cause in the early part of the 20th century.