Record revealed

Photographs of the British Black Panthers headquarters

These photographs, captured through police investigations, give a unique insight into the heart of the early British Black Panther movement, one of the principal Black Power organisations to form in the late 1960s.

Images

Image 1 of 3

Rear ground floor room of premises at 307 Portobello Road, W11. Photograph taken on 25 July, 1968 by police photographer.

Image 2 of 3

Rear ground floor room of premises at 307 Portobello Road, W11. Photograph taken on 25 July, 1968 by police photographer.

Image 3 of 3

Exterior of premises at 307 Portobello Road, W11. Photograph taken on 25 July, 1968 by police photographer.

Why this record matters

- Date

- 1968

- Catalogue reference

- CRIM 1/4962

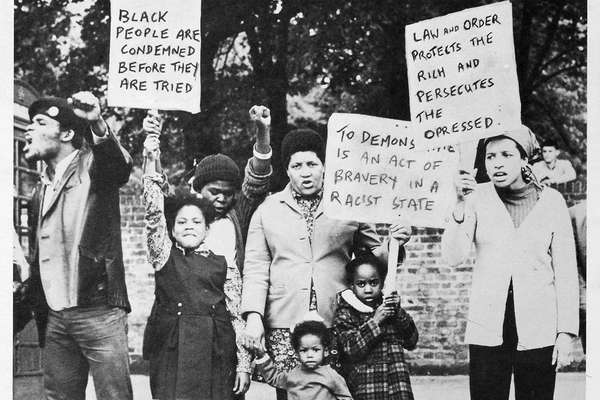

The 1960s and 1970s saw fresh waves of Black activism throughout the world, from the civil rights movement in America to unrest against colonial governments in the Caribbean. A new type of movement was forming, inspired by Black pride and Black self-determination, this movement emphasised economic as well as political independence and self-defence.

In 1967 political campaigner Stokely Carmichael, a central figure in the American Black Power movement who later adopted the name Kwame Ture, visited Britain and sent out a rallying message. While there had always been UK based fights against racism, this was a galvanising moment that gave the movement new energy and drove the creation of activist organisations. British authorities were fearful – they started to place such groups under surveillance at home and overseas.

One of the key organisations to form was the British Black Panther movement, inspired by its American counterpart and in response to the specific challenges faced by Black British activists. Obi Egbuna, a Nigerian born playwright and activist, had founded the organisation in April 1968. The organisation had a small and restricted membership, but a larger reach through community literature.

Egbuna’s influence was short lived. Later that year he was arrested on charges of threatening to murder police officers at Speakers Corner. He had written an article, to be published in the organisations official publication Black Power Speaks, that encouraged Black people to resist police violence. Unlike the US Black Panther Party who organised police patrols, this kind of radical self defence strategy was rarely actively pursued in the UK but was referenced in literature.

The organisation’s Black printer said he did not support the Panthers aims and ‘was very happy in this country’, and he passed the draft text on to the police. Egbuna was controversially held without bail for almost six months, eventually tried in the Central Criminal Court and given a suspended sentence (documents relating to Egbuna's attempts to get bail can be found in catalogue reference LO 2/479).

As part of this case police officers searched the headquarters at 307 Portobello Road, Notting Hill, for evidence against Egbuna and his fellow Panthers. Photographs of the interior and exterior of their headquarters were taken on 25 July 1968. Police noted the significant ‘slogans and signs showing that it was the Black Power Movement of the Black Power Party’.

The two interior images give a strong impression of the influences on the Panthers and what was important to them. The rear ground floor office included photographs of Robert Williams, an American civil rights leader, Ahmed Sékou Touré, first president of Guinea, and Che Guevara, Marxist revolutionary guerrilla leader.

The movement positioned themselves as part of global liberation struggles – as their surroundings showed – drawing connections through various anti-imperialist campaigns and a sense of solidarity through political Blackness. At times this international lens was seen to be at the expense of focusing on Black British struggles.

The walls also displayed a canvas with the classic Black Power symbols, a black panther and clenched fist. The central poster states ‘Black Power means liberation not ‘integration’ as 3rd class citizens’. This was a key shift in ideology at the time – these campaigners wanted freedom not just acceptance. Some elements of the movement were keen to align themselves with white working class struggles and others seeing them as separate fights.

Although the Panthers later moved from these headquarters, and their political and social goals changed, these photographs are an intimate and rare insight into this pioneering organisation at a particular moment in time; a visual representation of some of the ideals the movement valued most.

The British Black Panthers only lasted a few more years, but during this came a high point in the Black British Power Movement – the Mangrove Nine campaigns. By this point the organisation was non-hierarchical with Althea Jones-LeCointe as a leading figure in the group.

Related galleries

Featured articles

The story of

The Mangrove Nine

The trial of nine black protestors who were arrested while demonstrating in Notting Hill in the early 1970s became a public platform to criticise police racism.