Conflict in Southeast Europe

At the time of the First World War, British troops were part of an Allied force fighting against the Bulgarians and their allies in the Balkans. Serbia was successfully invaded by Bulgarian, Austro-Hungarian and German forces in October 1915, culminating in the division of the country into Bulgarian and Austro-Hungarian occupation zones.

As a result, Serbian forces retreated to Albania. They lost many men in the ice-cold conditions and the survivors evacuated to neutral Greece. They were joined there by Allied powers, made up of British, French and Italian forces, who landed in the Northern Greek port city of Salonika (now known as Thessaloniki). This lead to the creation of a Macedonian front, a traditionally side-lined theatre in narratives of the First World War.

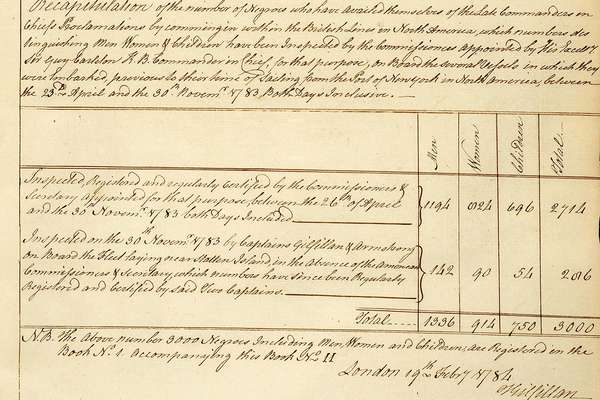

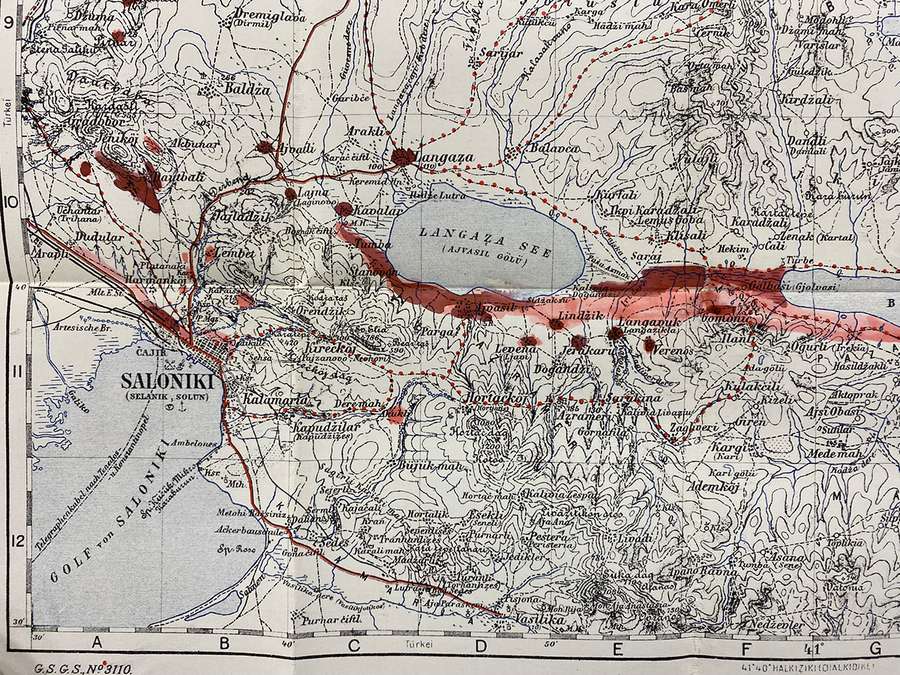

War Office Map of Salonika, showing the areas (in red) with high incidences of malaria. Catalogue reference: WO 32/5112

The 28th General Hospital

The British Salonika Force (BSF), commanded by Lieutenant-General George Milne, arrived at Salonika on 5 October 1915. With the arrival of British and allied troops, medical facilities needed to be established. A number of Casualty Clearing Stations were set up, as well as around 30 base hospitals.

One of these – the 28th General Hospital – was set up on the Monastir Road, close to the 4th Canadian General Hospital. The medical case sheets from this hospital still survive today in record series MH 106. Maps found in our collection also show how infrastructure was created to accommodate the sudden surge of troops to the area.

Alongside this influx of service personnel were medical and nursing staff. Lieutenant George Gibson described the arrival of nursing workers to Salonika in December 1915:

Our nursing staff arrived two days ago after having been five weeks at sea… they floundered up here in the pouring rain and in mud which takes one nearly to the knee, and I have never felt so sorry for any human beings.

Alan Wakefield and Simon Moody, Under the Devil’s Eye: The British Military Experience in Macedonia

The war diary for 28th General Hospital gives us insight into the harsh conditions experienced by those in the makeshift camps: often battered by extreme weather, from oppressive heat to snow, temperatures could vary wildly even in the same 24 hours.

The diary entries also give details of patient admission and discharges. 2 August 1916 saw 12 patients admitted and 98 discharged, and on the same day:

The rainfall was tremendous, + it was accompanied by an exceptionally strong gale, before the force of which the Officers’, Sergeants’, + men’s messes + the canteen were wrecked, + the Dispensary & all the stores only just managed to remain standing.

War diary for 28th General Hospital, 1916. Catalogue reference: WO 95/4933

Christmas Day of that year saw a 'gloriously fine sunny day', with concerts given to patients and personnel, but three days later the canteen and recreation room were again wrecked by a storm.

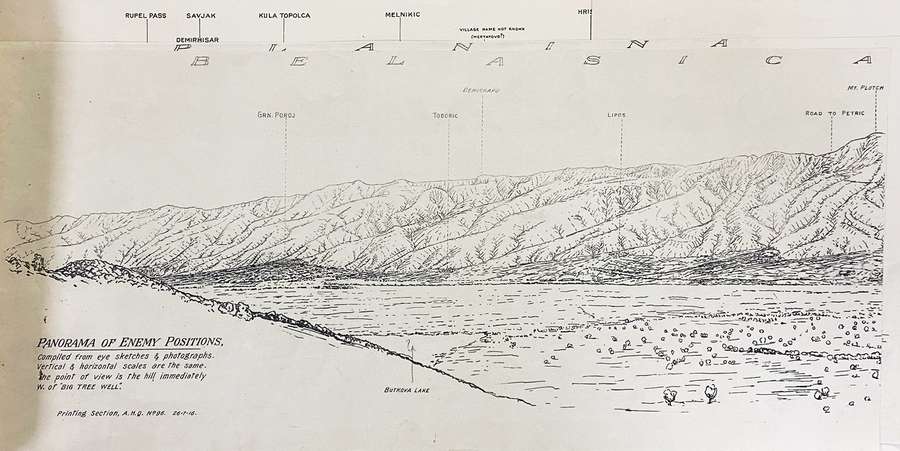

Not only did personnel and servicemen have to deal with the fluctuating extremities of the weather, the landscape was also tough. The mountainous terrain of the Macedonian front meant that supplies had to be carried by animals such as mules.

War Office Panaroma of enemy positions towards Belasica mountainous range. Catalogue reference: WO 153/1344

Our collection of medical case sheets show that eight Muleteers from the Macedonian Mule Corps were admitted to the 28th General Hospital from 1918 to 1919. Sadly all eight men died at the hospital.

A typical British field ambulance column in Macedonia, using horses and mules, 1916. © IWM (HU 51960)

On top of the extreme climate and terrain, service-personnel also had to contend with battlewounds and disease. Work on First World War medical records by volunteers at The National Archives has listed trench foot, gas poisoning, shell and gunshot wounds, shell shock, broken bones, tonsillitis, in-grown toenails and influenza as just some of the common ailments and afflictions faced by those living and fighting on the front lines.

But the sub-series of records from 28th General Hospital show that the greatest cause of admission there, by a distance, was malaria.

The War Office versus malaria

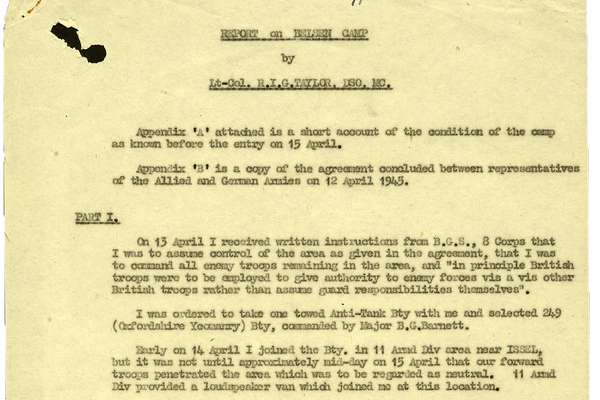

Cabinet Minutes in April 1917 record the summary of a report by Colonel Hunter of the Army Medical Service, and President of the Mediterranean Sanitary Commission, on the extent of the condition among troops on the Macedonian front. He wrote that:

During the past year it affected more than one fourth of the total forces. The malarial infection has therefore been not only of unusual magnitude, but also of exceptional intensity, as shown by the severity of its clinical features, the post-mortem changes found in fatal cases, debilitating effects, and subsequent frequency of relapse.

Summary of a report by Colonel Hunter. Catalogue reference: CAB 24/10/2

The report noted that more than two-thirds of the admissions into the Field Ambulances were for malaria – an extraordinary threat. In 2522 case sheets from 28th General Hospital, Malaria is mentioned 559 times, compared to the next highest occurrence, pneumonia, with 178. 'Gunshot wound' appeared 130 times in the sample.

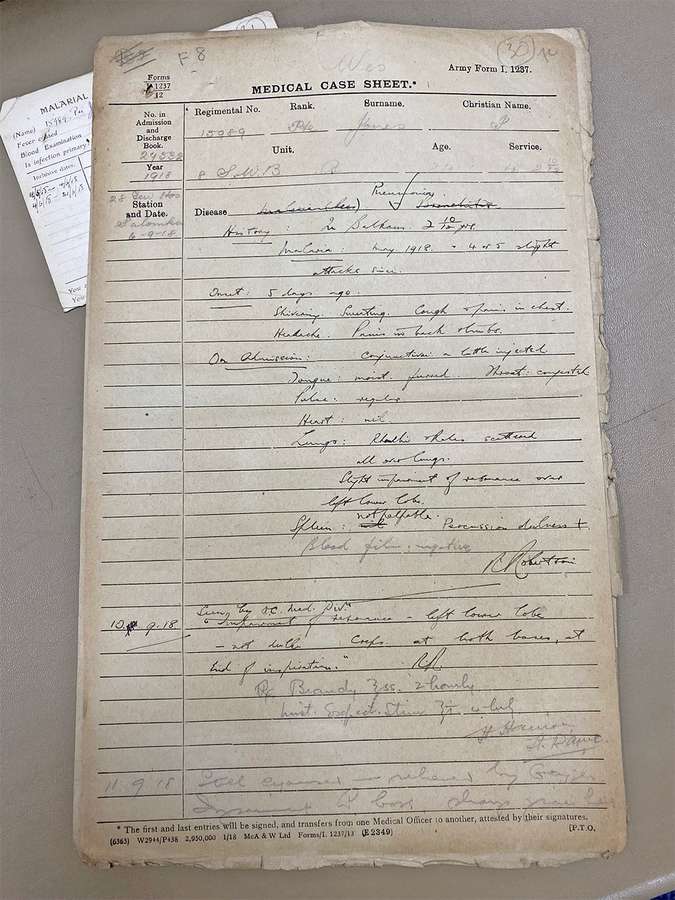

The medical case sheet for Isaac Jones of the South Wales Borderers shows that he caught malaria in May 1918 and had four or five attacks over the next few months. Sadly he passed away from pneumonia in 28th General Hospital on 14 September 1918.

Isaac Jones’ medical case sheet. Catalogue reference: MH 106/2381/22

Efforts were made to limit the risk. The British medical doctor Sir Ronald Ross had discovered the transmission of malarial parasites by mosquitoes in 1897. He worked as a malaria consultant for the army during the war, and his expertise was sought to save lives and money.

Some treatments did exist. Quinine, first isolated from the Cinchona bark in 1820, had been used to treat malaria from the mid-19th century. Ross explained in a letter that its use was necessary, but would not be a cure:

…The suggestion to cinchonise [give quinine to] the Greeks in the villages at once is very important. Mosquito-proof shelters for sentries and as much proofing as possible are also called for, and mosquito brigades and mosquito-reduction near camps is essential.

Experience shows that if the mosquitoes are allowed to abound as before, quinine, even in very considerable prophylactic doses, merely has the effect of keeping down the fever, while allowing the men to become infected... [W]hen the men stop taking the quinine they get fever again, and their health is always damaged by the presence of any parasites at all in the body.

However it is proper to do everything possible, and this will save money in the end. I think that you have still about two months grace left before General Malaria comes on the field against you.

Sir Ronald Ross to Surgeon General Alfred Keogh, 29 February 1916. Catalogue reference: WO 32/5112

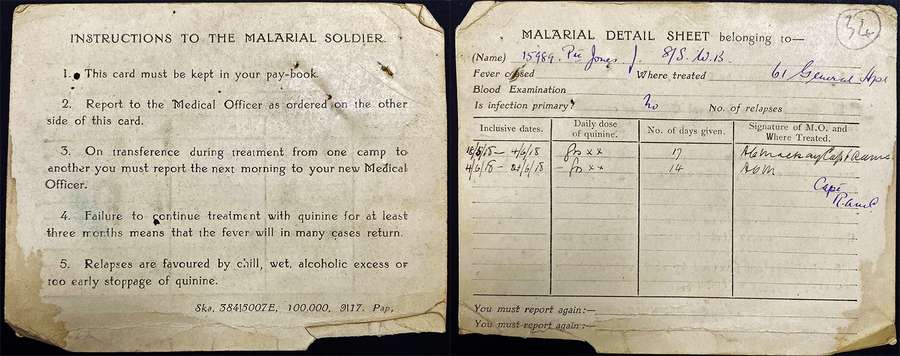

As Ross recommended, quinine was administered as a prophylactic to troops, as well as to villagers and labourers. Many of the casesheets in the Salonika sub-series include a malarial detail sheet which recorded soldiers' daily doses.

Instructions to the Malarial Solider

- This card must be kept in your pay-book.

- Report to the Medical Officer as ordered on the other side of this card.

- On transference during treatment from one camp to another you must report the next morning to your new Medical Officer.

- Failure to continue treatment with quinine for at least three months means that the fever will in many cases return.

- Relapses are favoured by chill, wet, alcoholic excess or too early stoppage of quinine.

Malarial detail sheet with 'Instructions to the Malarial Soldier', 1918. Catalogue reference: MH 106/2381/22

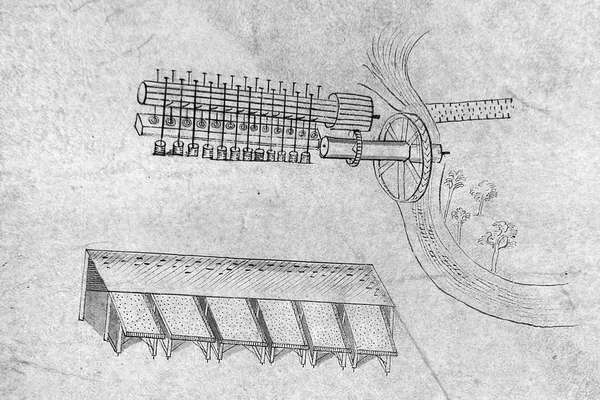

In addition, extensive malarial surveys of the area were carried out. Men were issued mosquito nets made up of two curtains (9 feet by 5 feet, 6 inches), at a weight of 1 lb 9 oz.

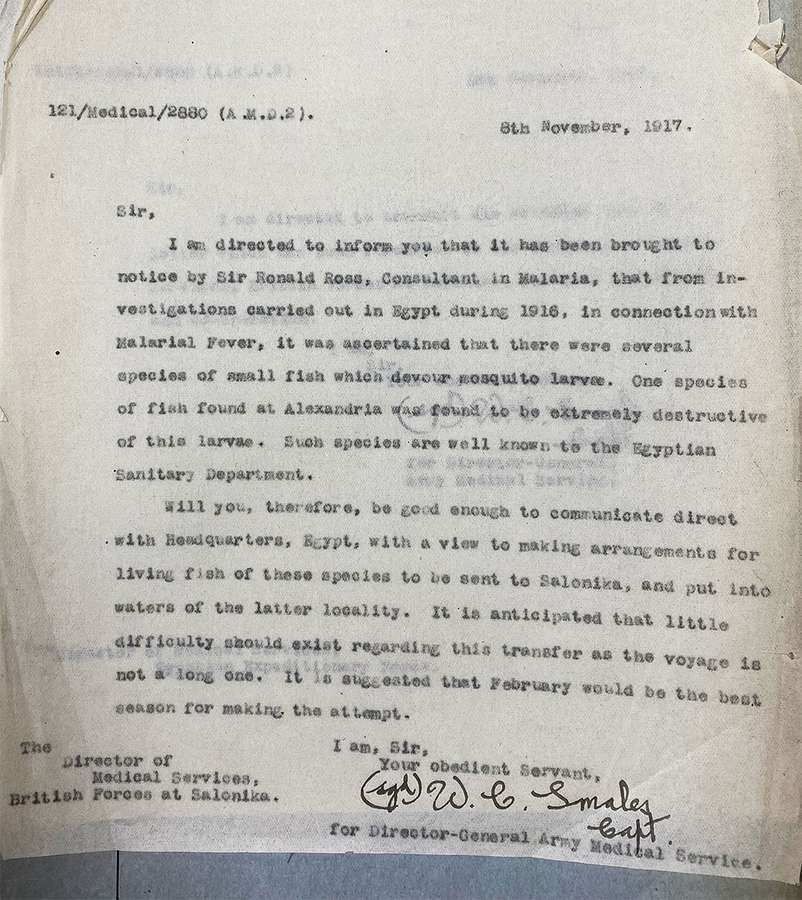

It was also found that a certain species of fish in Egypt could help keep mosquito numbers down – because they ate mosquito larvae. A letter from November 1917 shows that Captain WG Smales, the Director General of Army Medical Services, wrote to the Director of Medical Services for the British Forces in Salonika to discuss transferring fish from Alexandria:

Sir,

I am directed to inform you that it has been brought to notice by Sir Ronald Ross, Consultant in Malaria, that from investigations carried out in Egypt during 1916, in connection with Malarial Fever, it was ascertained that there were several species of small fish which devour mosquito larvae. One species of fish found at Alexandria was found to be extremely destructive of this larvae. Such species are well known to the Egyptian Sanitary Department.

Will you, therefore, be good enough to communicate direct with Headquarters, Egypt, with a view to making arrangements for living fish of these species to be sent to Salonika, and put into waters of the latter locality. it is anticipated that little difficult should exist regarding this transfer as the voyage is not a long one. It is suggested that February would be the best season for making the attempt.

I am, Sir, Your obedient Servant,

(sgt) W. G. Smales Capt.

Letter to the Director of Medical Services for the British Forces in Salonika, November 1917. Catalogue reference: WO 32/5112

Despite these efforts, malaria still caused extensive damage to the troops stationed on the Macedonian front. There was only so much that could be done.

The end of the campaign

The conflict in Macedonia ended with the defeat of Bulgaria and liberation of Serbia in October 1918. The War Diary for 28th General Hospital includes a Special Order thanking the BSF for their gallantry, determination and devotion, noting that:

... this result has been obtained only by your extraordinary exertions after three summers spent in a malarious country and against obstacles of great natural and artificial strength. What appeared impossible has been accomplished….. No one knows better the odds against which you have had to contend, and I am proud to have had the honour of commanding you.

Special Order from General George Milne, 1918. Catalogue reference: WO 95/4933

Despite these successes and the challenging ordeal the forces had to endure, the Macedonian front is regarded as one of the forgotten 'side-shows' of the war. Records like the medical case sheets in MH 106 can serve to remind us of the individual toil of those working and fighting there.

Records featured in this article

-

- From our collection

- Sub-sub-series within MH 106

- Title

- Medical case sheets for soldiers treated at 28th General Hospital, Salonika

- Date

- 1915–1919

-

- From our collection

- WO 32/5112

- Title

- War Office Map of Salonika showing areas with high incidences of malaria

- Date

- 1916–1917

-

- From our collection

- WO 95/4933

- Title

- War diary for 28th General Hospital, Salonika

- Date

- October 1915 – June 1919

-

- From our collection

- WO 32/5112

- Title

- Report on the incidence of malaria in the Salonika army, and measures proposed and taken to address it

- Date

- 1916–1917

-

- From our collection

- CAB 24/10/2

- Title

- Summary of a report by Colonel Hunter on the extent of malaria among forces in Macedonia. Catalogue reference: CAB 24/10/2

- Date

- 10 April 1917

References

- Alan Wakefield and Simon Moody, Under the Devil’s Eye: The British Military Experience in Macedonia 1915-1918 (2004).

- Captain Cyril Falls, Official History of the War: Military Operations in Macedonia (London, 1933-1935).

- Major JPB Condon, The Macedonian Mule Corps 1916-1919 (1979).

All works referenced are available in The National Archives Library.

More in-depth details of the Salonika campaign and Balkan front can be found on The Long, Long Trail website (last accessed 17 September 2024).