The Women's Suffrage Movement

Alice Hawkins was active in the militant suffrage society the WSPU from 1907 and was a consistent figure in their campaigns. The National Archives has a world-renowned collection of documents relating to the 20th-century part of the women’s suffrage movement. The wealth of records cross many government departments, illustrating the huge impact, particularly the militant suffrage campaign, had across government.

A photograph of the Deputation of Working Women in The Suffragette, 31 January 1913. Catalogue reference: ASSI 52/212.

These records also highlight many personal experiences of male and female campaigners for the vote. Following Alice’s experience gives us an insight into how the suffrage campaigns affected the real lives of individuals.

Working women and the vote

Alice Riley was born in 1863 in Stafford, one of nine children. By the age of 13, after the family had moved to Leicester, she was working in the shoe trade, creating boots and shoes just as her father did. Her early life can be traced through our census records.

In 1884 she married Alfred Hawkins. The pair met at an early socialist meeting, and from then on Alfred would actively support Alice’s work to get women the vote.

Alice became active in the militant suffrage society – the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) – and was a consistent figure in their campaigns. She helped establish the WSPU in Leicester.

Alice was first arrested in February 1907, when she was one of 29 women sent to Holloway Prison after a march on Parliament.

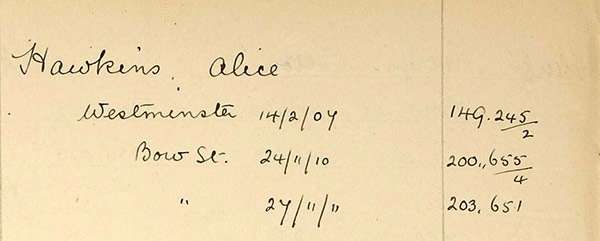

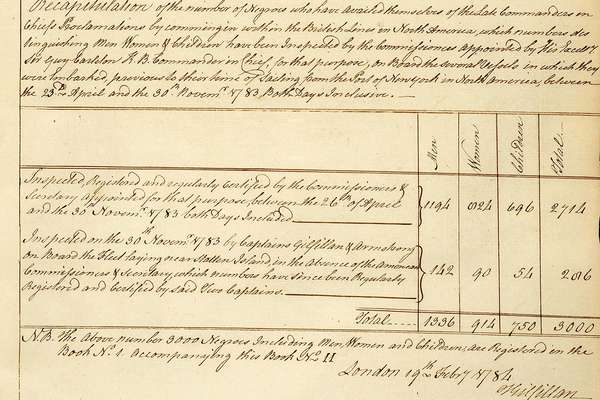

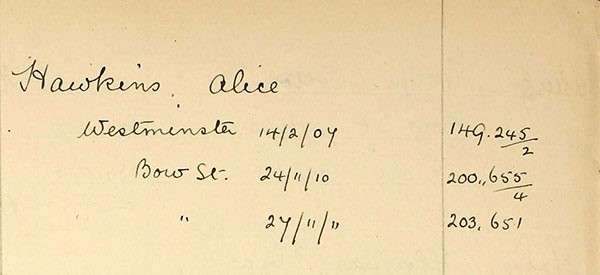

Hawkins, Alice

Westminster 14/2/07

Bow St 24/11/10

'' 27/11/11

The entry for Alice Hawkins in the index to suffragettes arrested. Catalogue reference: HO 45/24665.

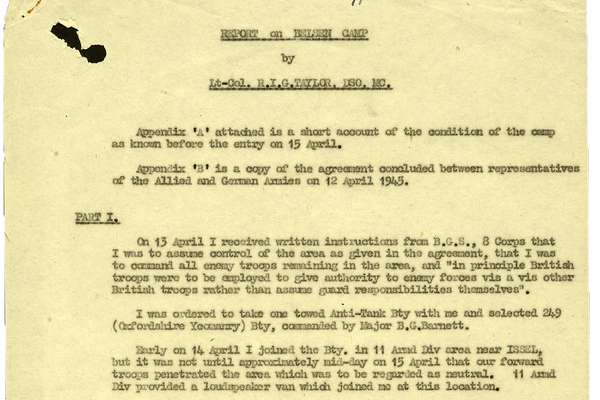

Record revealed

List of suffragettes arrested from 1906–1914

More than a thousand people who supported women’s right to vote were arrested for their activism. This document records them – and includes some famous names.

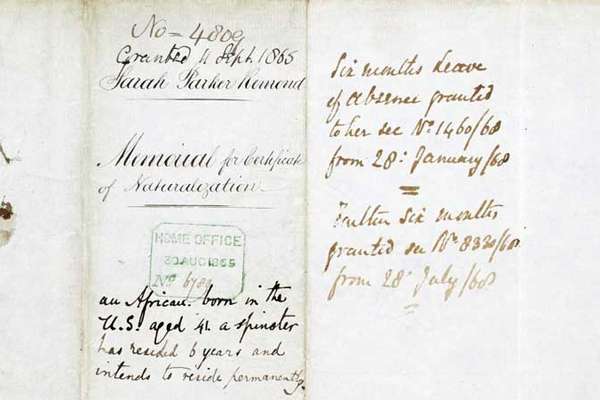

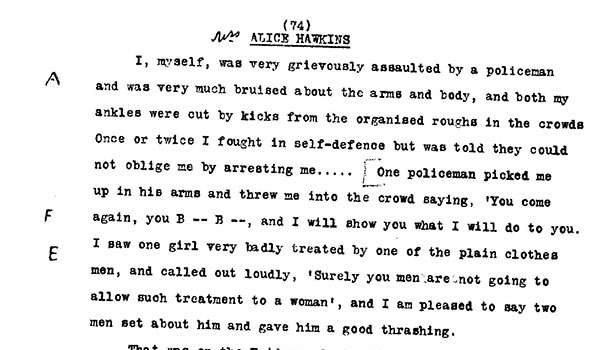

Black Friday: a turning point

On 18 November 1910, Alice was one of around 300 women on a delegation led by Emmeline Pankhurst to Parliament. They were protesting against the Prime Minister’s decision not to allow any more time on a Bill to give approximately 1 million women the vote. This resulted in lengthy and violent clashes with the police.

Following the protest, around 200 women claimed they were injured – and in some cases sexually assaulted – by the police. These shocking clashes on 18 November 1910 became known in suffrage history as ‘Black Friday’.

This was a turning point in the movement. Suffrage campaigners believed that the government cared more about damage to property than the damage done to women’s bodies. After the clashes, evidence was gathered and submitted to the Home Office. In their own words these women powerfully described how they were treated by police.

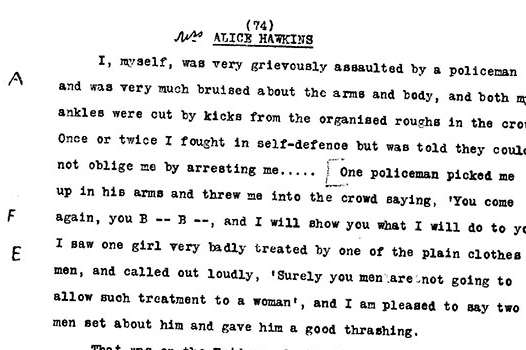

Alice provided her own testimony, in which she details how she was treated on this fateful day. She described being assaulted by a policeman.

I, myself, was very grievously assaulted by a policeman and was very much bruised about the arms and body, and both my ankles were cut by kicks from the organised roughs in the crowds. Once or twice I fought in self-defence but was told they could not oblige me by arresting me..... Once policeman picked me up in his arms and thew me into the crowd saying, 'You come again, you B -- B --, and I will show you what I will do to you. I saw one girl very badly treated by one of the plain clothes men, and called out loudly, 'Surely you men are not going to allow such treatment to a woman'., and I am pleased to say two men set about him and gave him a good thrashing

Alice Hawkins' Black Friday testimony. Catalogue reference: MEPO 3/203

-

- From our collection

- MEPO 3/203

- Title

- Alice Hawkins' Black Friday testimony as submitted as evidence

- Date

- 1911

The Deputation of Working Women

Alice was determined to win the vote. She participated in protests outside Parliament and window smashing campaigns but, like many suffragette campaigners, she also acknowledged the power of words.

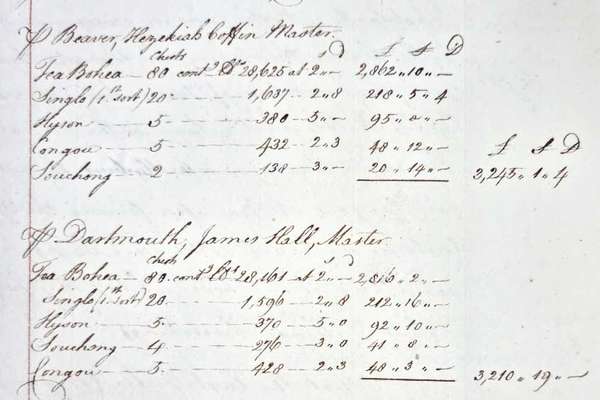

In 1913, the WSPU issued a call to working women from across the country to be part of a deputation to speak with David Lloyd George. Representing a range of trades, the deputation spoke about the struggles they faced as women and the striking disparity in wages compared to men in similar jobs. Their aim was to articulate why, for many working women, gaining the vote was just the first (very important) step in the struggle for equality.

The Deputation of Working Women, pictured in the Illustrated London News, 1913. Catalogue reference: ZPER 34/142.

Alice was one of the deputation: she represented herself, but also the women workers in the boot and shoe trade in Leicester. In her powerful statement to Lloyd George, Alice referenced the terrible, sweating conditions she worked in, and the inequality in her pay compared to men doing the same job. She talked about the irony that, under the proposed bill, her two sons would have the vote but she would not.

I have two sons… Those sons under this new bill – the Manhood Suffrage bill – would have votes. I, the mother who brought them into the world, have nothing

Alice Hawkins

During the deputation, Lloyd George gave assurances that amendments to the Reform Bill would be carried. However, the amendments were dropped that same evening. This was one of many in a long line of frustrations for suffrage campaigners.

When did working women get the vote?

In 1918, the Representation of the People Act 1918 came into law, providing some women with a vote in Parliamentary elections for the first time. Many working class women would not have gained the vote under this act. There was also an age clause. Alice was one of the approximately 20% of women over 30 who would not have met the property qualification to vote, despite the huge lengths she went to in her fight for equality.

Alice won her right to vote a decade later, under the 1928 Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act.

After her involvement in the women’s suffrage movement, Alice continued to be a lifelong campaigner for equality through the trade union movement. In 2018 a statue of Alice was unveiled in Leicester Market Square.

The statue of Alice Hawkins. Image: Kiran Parmar, CC BY 2.0.

Read more

Blog: Keeping tabs on suffragettes: the official watchlist

What can we learn from the official watchlist of suffragettes, which contains details of over 1,300 arrests?

Blog: The Archivists’ Guide to Film: Suffragette

In this post from our series in which staff at The National Archives write about favourite films, Katie Fox and Liz Fulton discuss Suffragette (2015)

Blog: The Representation of the People Act 1918: Votes for (some) women, finally

What did the passing of the Representation of the People Act mean for the lives of women? And whom did it leave out?

Teaching resource: Suffrage Tales

This resource, designed to be used in the classroom is based on a film made by students drawing upon a wide range of documents from our collection