Record revealed

A misleading Victorian medical device

Unexpectedly surviving among some court papers, this medical belt was one of a number of Victorian devices that claimed to use the power of electricity to cure ailments.

Images

Image 1 of 4

Harness’ Medical belt sold by the Medical Battery Company.

Image 2 of 4

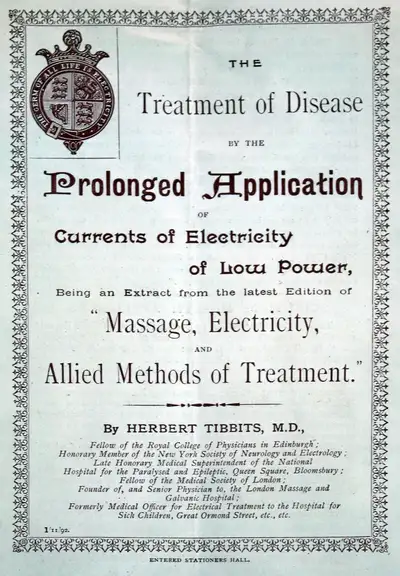

Pamphlet by Dr Herbert Tibbits, which featured an advertisement for the Medical Battery Company on the back page.

Transcript

The Electropathic and Zander Institute, for the treatment & cure of disease by electricity, and Dr. Zander's Swedish mechanical exercises.

Sole proprietors – The Medical Battery Company Limited, 52, Oxford Street, London, W. (Corner of Rathbone Place).

Image 3 of 4

Pamphlet by Dr Herbert Tibbits, which explained how the medical belt could be used.

Transcript

The Treatment of Disease by the Prolonged Application of Currents of Electricity of Low Power, Being an Extract from the latest Edition of “Massage, Electricity, and Allied Methods of Treatment.” By Herbert Tibbits, MD., Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians in Edinburgh: Honorary Member of the New York Society of Neurology and Electrology; Late Honorary Medical Superintendent of the National Hospital for the Paralysed and Epileptic, Queen Square, Bloomsbury; Fellow of the Medical Society of London; Founder of, and Senior Physician to, the London Massage and Galvanic Hospital; Formerly Medical Officer for the Electrical Treatment to the Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street, etc, etc.

Image 4 of 4

Folder packet containing evidence for the libel case Herbert Tibbits (Plaintiff) v Alabaster, Gatehouse and Kempe (Defendents).

Transcript

This packet contains the Exhibits, two in number. (viz. the belt and the sketch) referred to by Lord Kelvin of the Glasgow University, a witness for the defendants, in his deposition on oath taken at Glasgow on the 11th day of February 1893, before me as Special Examiner under order made by Master [?], Master in Chambers, dated 11th February 1893. J. Muirhead, Special Examiner.

Why this record matters

- Date

- 1893

- Catalogue reference

- J 17/283

In the 19th century, the allure of electricity permeated consumer culture and even understandings of the body. Electric devices were sold in the Victorian period as an alternative to medicines prescribed by doctors. Adverts for devices, such as medical belts, appeared in popular lay magazines and the local press.

Proprietor Cornelius Bennett Harness of the Medical Battery Company stated his medical belt would cure nervous complaints, indigestion, sleeplessness and impart ‘new life and vigour’. Domestic electrical devices also had the added benefit of patients being able to self-administer and control their own treatment.

Used as evidence for a court case pleading heard at the Queen’s Bench (one of the three Senior Courts of England and Wales), the medical belt was found tucked into an unassuming packet at The National Archives. Physical evidence like this tends to be weeded out before it comes here.

Why was it used as evidence? In the 1890s, the editors of The Electrical Review reported extensively on the charlatan nature of electro-therapeutics, publishing a series of exposés against The Medical Battery Company. They detailed experiments that showed the chemical effect of metals on the skin could only produce a small amount of electricity and could not penetrate the skin, thereby giving no therapeutic effect.

As part of their frequent exposés they called out the professional morals of a medical man named Herbert Tibbits, who supported The Medical Battery Company in their promotional material. As a result, Tibbits sued the proprietors of the magazine, claiming £5,000 for libel. During the libel trial, one of Harness’s medical belts was examined by the eminent scientist Lord Kelvin, then the President of the Royal Society.

In his witness testimonial, dated 11 February 1893, Kelvin damningly noted ‘This belt, or any other belt constructed to the same pattern is incapable of generating an electric current without additional connecting wires to complete the circuit between the copper and zinc discs, and if worn on the body as it is, it would be electrically ineffective’.

Newspaper reports show that editors of The Electrical Review ended up winning the case. Tibbets was later struck from the Medical Register.

This medical belt and court case give us today insight into professional attitudes towards medical electricity in the Victorian period. Despite these attitudes, electro-therapeutics continued to flourish on the margins of and even within professional medical practice.

Featured articles

The story of

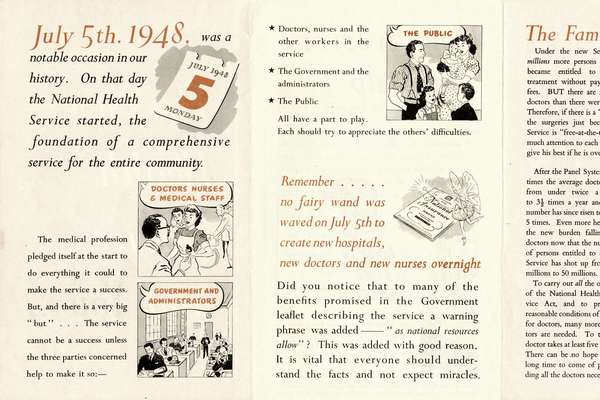

The foundation of the NHS

Explore the foundations of the NHS, one of Britain's most well-known and loved institutions.

Blogs

-

Blog

Electro-therapeutic cures in the Victorian Age

Explore the allure of electricity permeated 19th-century consumer culture and even understandings of the body.