In pictures

The land girls of the Women’s Land Army

During the First and Second World Wars, while men went to fight on the front lines, thousands of women left towns and cities across the country to move to the nation’s farms. Our records provide a unique insight into the ‘land girl’ experience as they fought in the ‘Battle for Bread’.

First World War Women’s Land Army certificate

- Date

- 1914–1918

- Catalogue reference

- MAF 42/8

The Women’s Land Army (WLA) was created in 1917 to call women to work in agriculture, filling the gap in the labour force left by men going to fight in the First World War. Government officials worked hard to encourage women to join.

This certificate was issued to women who served in the Land Army to thank them for their wartime service. It states that ‘every woman who helps in agriculture during the war is as truly serving her country as the man who is fighting in the trenches, on the sea, or in the air.’ It is signed by the Director General of Food Production and the President of the Board of Agriculture.

The Women’s Land Army was disbanded at the end of the First World War, but was restarted in 1939 with the outbreak of the Second World War.

Land girl Vivien Kipling holding a calf

- Date

- 1939–1945

- Catalogue reference

- MAF 59/152

This photograph shows land girl Vivien Kipling holding a calf and was published in the Land Girl magazine in 1944. She joined the WLA at the age of 18 and went on to serve for ten years until its disbandment in 1950. When this photograph was taken, Vivien was forewoman at Lower Woodside Dairy Training Centre in Hertfordshire.

Women’s Land Army recruiting poster

- Date

- 1939–1945

- Catalogue reference

- MAF 59/18

The Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries worked with the Ministry of Information to produce publicity material to encourage women to join the Land Army. One slogan they commonly used was 'Win the Battle for Bread'.

A variety of design techniques and imagery were used to depict the Land Army. This poster presents a modern design incorporating a partially coloured photograph in blue and yellow depicting a land girl driving a piece of farm machinery. This kind of farming responsibility was initially considered unsuitable for women, but many land girls successfully took on these roles all over the country and enjoyed doing so. This poster presents a scene of strength and independence promoting an exciting and liberating new activity for potential recruits.

Women’s Land Army index card for Amelia King

- Date

- 1943

- Catalogue reference

- MAF 421/1

Amelia King was a Black woman who lived in East London working as a box maker before applying to join the WLA in 1943. She was rejected by the Essex branch who claimed it wouldn't be able to find a local farm that would accept her due to the colour of her skin.

This led to a public outcry, with solidarity meetings, leaflets, press publicity and questions in parliament. A cause of racial tension was the arrival of White American servicemen who were used to racial segregation at home. The British authorities feared offending their allies but did not want to promote racial segregation. This caused problems for Black servicemen, who were often harassed in public places.

Amelia joined the Hampshire WLA branch in 1943, working at Frith Farm in Fareham until 1944 when she moved to the London and Middlesex branch.

More than 90,000 index cards like this have been digitised and are available online.

Women’s Land Army recruiting poster

- Date

- 1939–1945

- Catalogue reference

- INF 13/140

Publicity posters were not only trying to attract women to join the Land Army, they also acted to promote the services of the land girls to potential employers. At first some farmers expressed scepticism about women working in agriculture, concerned both about their competence and the challenging of gender norms.

This poster is an example of this design objective. It shows an idyllic pastoral scene with a beaming woman holding the reins of a horse with a farmer gesturing to her with his pipe and saying 'We could do with thousands more like you..' The land girl is presented in a traditionally feminine way, while at the same time her effectiveness on the farm is clearly promoted.

'Popular misconceptions' cartoon from The Land Girl magazine

- Date

- 1940

- Catalogue reference

- MAF 59/21

This cartoon by artist Mary Fedden was printed in the Land Girl magazine in December 1940. Mary Fedden was a land girl at the time, having graduated from the Slade School of Fine Arts, London, in 1936.

The cartoon, titled 'Popular misconceptions', contrasts an idealised view of the land girl labelled 'as we hope we look' with a realistic view labelled 'as we generally do look'.

After the war Mary Fedden continued her successful art career. In 1951 she was commissioned to create a mural for the Festival of Britain. She later taught painting at the Royal College of Art, where her pupils included David Hockney.

Rat catching

- Date

- 1939–1945

- Catalogue reference

- MAF 59/154

As well as tending to crops and livestock, land girls also took on other important but unpleasant tasks such as clearing rodents off the farms. This photograph shows three land girls proudly displaying the rats they had caught.

L. Clark, a land girl working in Leicestershire, wrote in the Land Girl magazine that she had redirected exhaust fumes into rat holes: ‘Arming ourselves with sticks we waited till the poisonous fumes from the exhaust pipe wound their way into the underground labyrinths of the rats' homes. Suddenly, out popped a brown head with two beady eyes. Bash! One more of Hitler's helpers was removed; only a little helper maybe, but one who can cause a great deal of damage to our country's corn supply.'

Listen to our podcast on the Women's Land Army for more WLA stories.

Poster of a land girl by Laura Knight

- Date

- 1939–1946

- Catalogue reference

- INF 3/108

This painting by British artist Dame Laura Knight was commissioned by the Ministry of Information to be used to publicise the Women’s Land Army. Its medium is watercolour, gouache and charcoal and it depicts a woman ploughing a field with two horses. Laura Knight had direct experience of working on farms gained during the First World War, so she knew the subject well.

She had clear opinions on how land girls should be presented in order to promote their work most effectively. In a letter about the commission she wrote: 'That there should be one girl only with the plough is important, for it seems that farmers will not engage girls as a rule for that work as it is considered too expensive because they say it take 2 girls to work in place of one man, but there are girls such as this one who can manage a plough on her own, and she cuts as straight a furrow as any man.'

Featured article

The story of

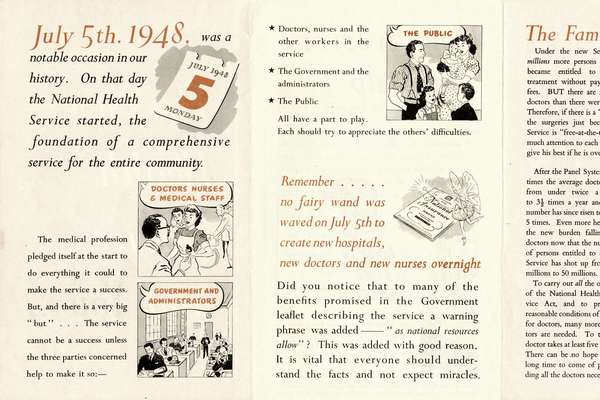

The foundation of the NHS

Explore the foundations of the NHS, one of Britain's most well-known and loved institutions.