In pictures

Historic food and drink at Christmas

Food and drink have been a central part of Christmas celebrations for centuries. But did 17th-century Brits eat turkey? Did they drink mulled wine? And which king ordered 19,000 litres of alcohol for their festivities?

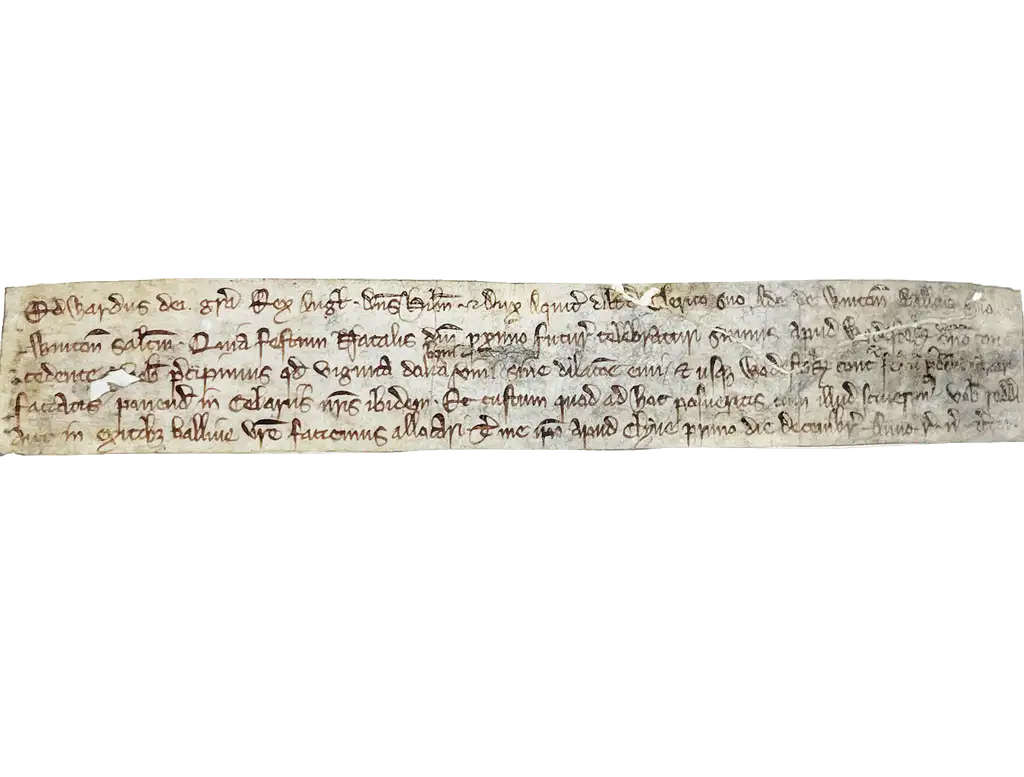

The fish and wine order for Edward I’s Christmas feast

- Date

- 1274

- Catalogue reference

- SC 1/14/98

At the beginning of December 1274, Edward I sent his bailiff, Adam of Winchester, two letters ordering fish and wine for his Christmas feast, which would be held that year at Woodstock in Oxfordshire. He required 21 loads of fish and 20 tuns of wine. A tun of wine was about 950 litres, so this was about 19,000 litres of wine.

After writing the wine order for ‘viginta dolia vini’ [20 tuns of wine], the clerk has gone back and added ‘boni’ – the Latin word for good. He, or the king looking over his shoulder, clearly wanted to ensure that the Christmas wine was to the king’s taste.

As well as Edward’s orders, we also hold the bill Adam sent to the king after purchasing the Christmas treats. It includes the expenses for carrying all of the fish and wine to Woodstock and an entry for the purchase of 400 haddock for 20 shillings.

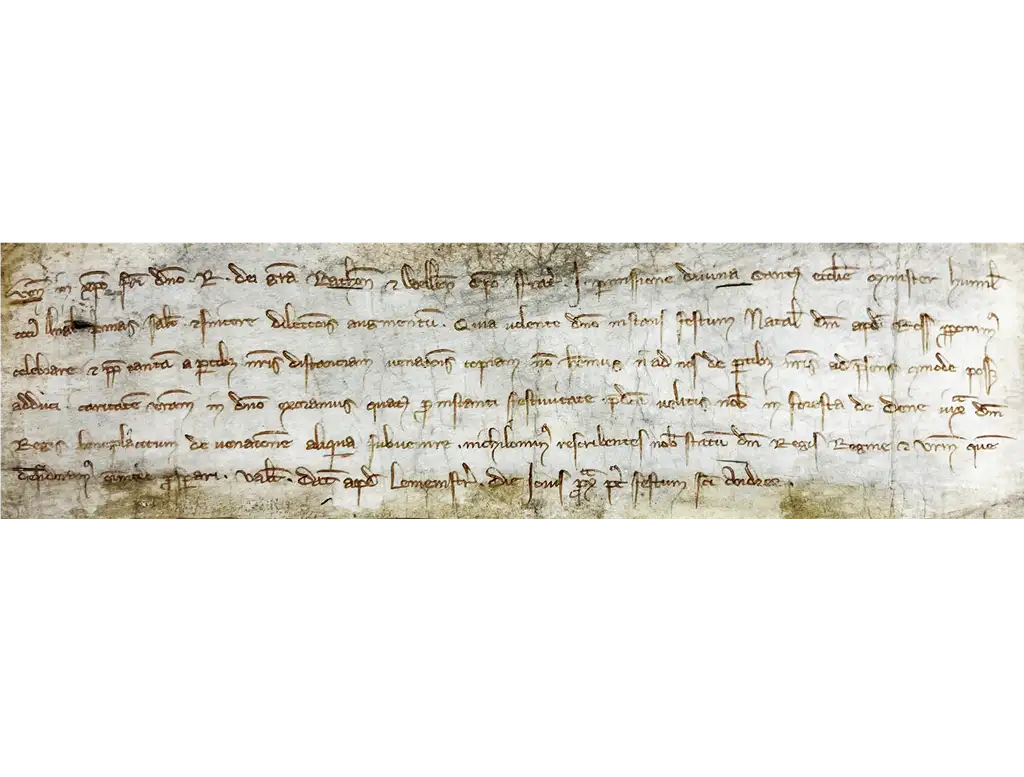

A letter from the archbishop of Canterbury ordering venison for his Christmas feast

- Date

- 1282

- Catalogue reference

- SC 1/24/44

On 3 December 1282, Archbishop John Pecham was looking ahead to his Christmas feast. He was planning to celebrate at Rochester, but there were no suitable hunting grounds nearby to supply him with deer for the ‘festum Natalis Domini’, the feast day of the birth of the Lord.

He wrote this letter to the bishop of Bath and Wells, asking him to provide venison from the Forest of Dean, around 150 miles from Rochester. As well as letting us know his plans for Christmas, this also reminds us of the web of trading and exchange routes across Britain in the period.

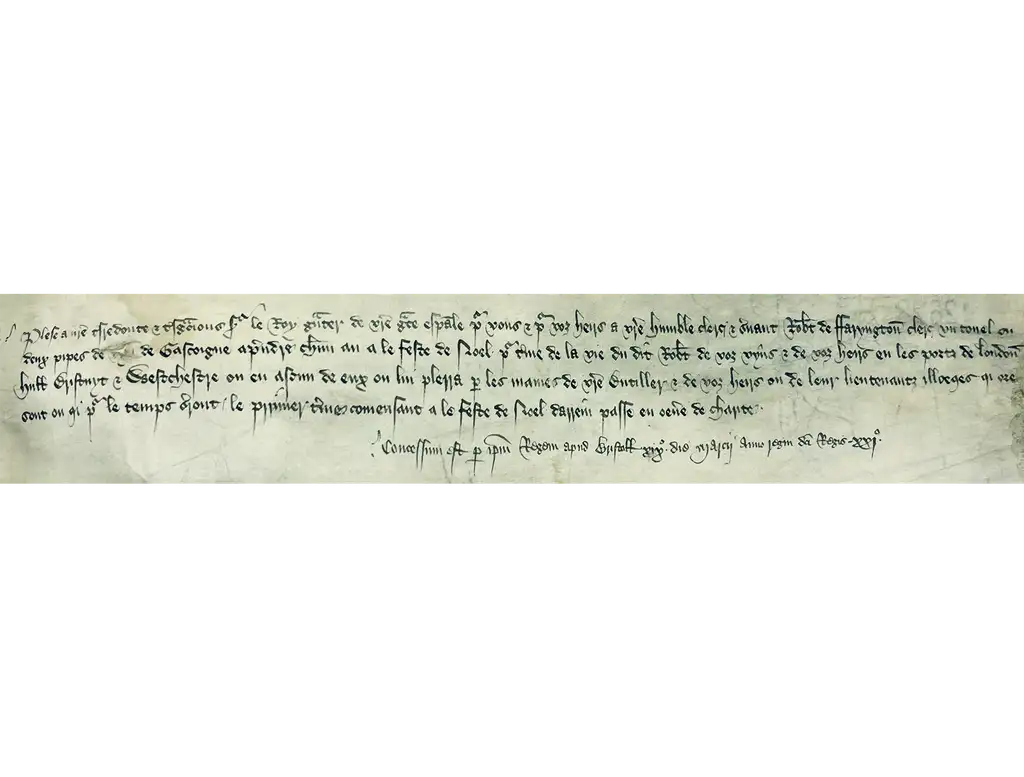

A petition asking the king for a tun of wine every Christmas

- Date

- 1398

- Catalogue reference

- SC 8/185/9244

Robert Faryngton, a clerk in the king’s service, sent this petition to King Richard II in March 1398, asking to be granted a tun or two pipes of Gascon wine every Christmas for the rest of his life. A tun of wine was about 950 litres, so more than 1,250 standard bottles of wine.

The petition, which is in French, has a note at the bottom in Latin that reads ‘This was granted by the King at Bristol on the 19th day of March in the 21st regnal year of the same king [1398]’. There is confirmation of this grant in the patent rolls, the records of the king’s public commands, which backdates it to the previous Christmas, so presumably, Faryngton could pick up his first tun immediately. For convenience, the wine could be collected at any of London, Hull, Bristol or Chester ports.

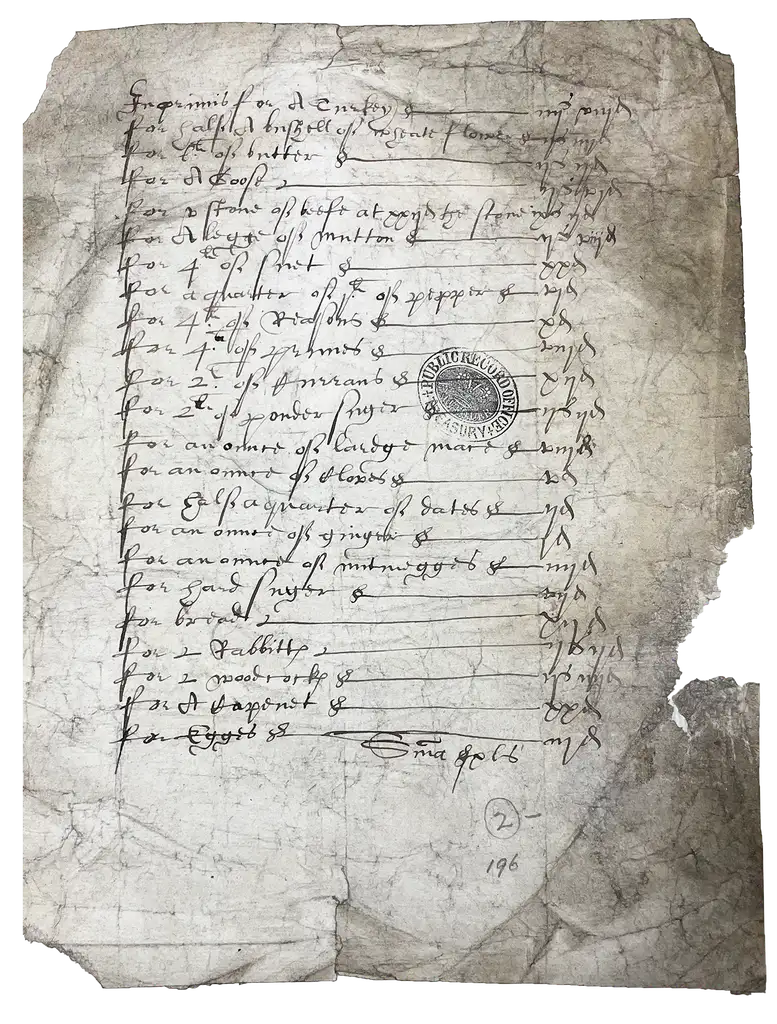

A 17th-century Christmas food list

- Date

- 1622–1625

- Catalogue reference

- SP 46/66/fo195-196

This account is a list of food for the Christmas period with costs. At the top of the first page, the list starts ‘Your supper for the 23rd and 25th of December’, and includes ‘a dozen of larks’. This page, the second page of the list, includes some food that we would recognise as Christmas food today, such as a turkey (first on the list) and a goose (fourth entry down). But it also includes some more unusual fare such as ‘2 woodcocks’ (a nocturnal wading bird).

Household accounts like this one end up in The National Archives’ State Papers collection almost by accident – we don’t know whose Christmas feast this was, as there are no names on the document, but it seems like they ate well. As well as a range of different meats, there is a long list of expensive imported ingredients, including ginger, pepper, and dates.

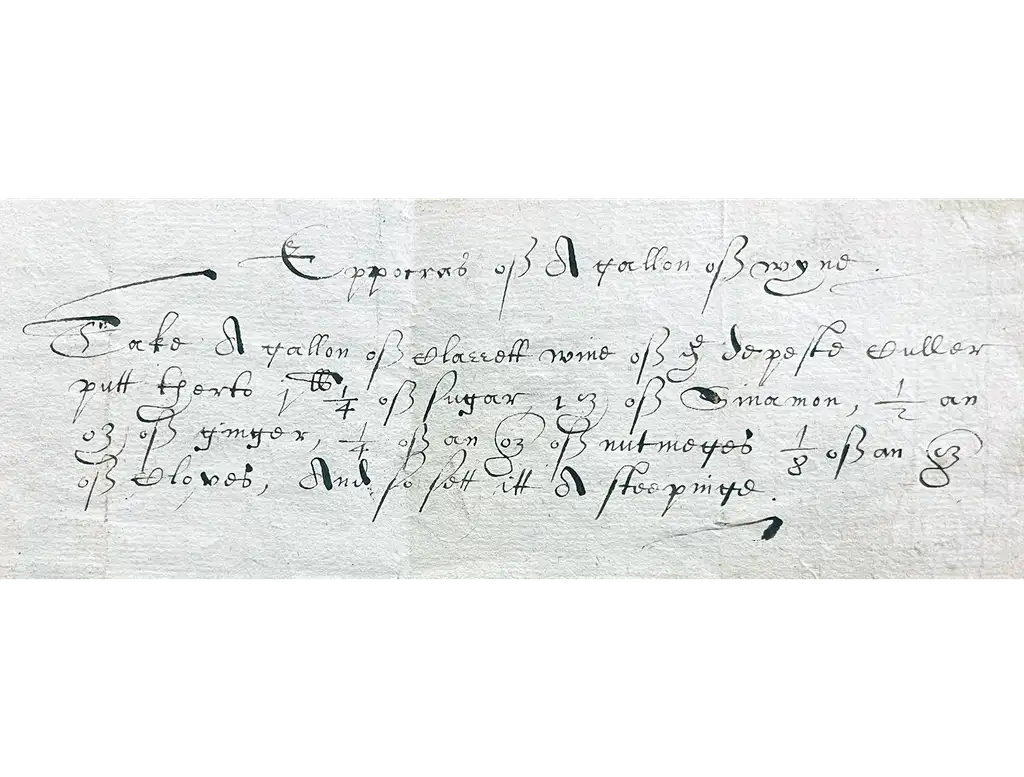

A recipe for Eppocras, a spiced wine drink

- Date

- 1600–1660

- Catalogue reference

- WARD 2/29/96A/25

This recipe isn’t specifically for Christmas, as people in the Middle Ages and Early Modern period drank spiced wine throughout the year, but it is similar to the modern festive drink of mulled wine. The recipe calls for a gallon of claret wine, sugar, cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg and cloves. All of the ingredients are put together, then the recipe instructs the cook to ‘sett itt a steepinge’.

The drink would have been served hot or cold, and was a way to use up older wine. The name ‘Eppocras’ (often spelt Hippocras in other recipes) comes from the method of filtering a liquid through a linen bag to remove the solids, which was invented by the 5th-century Greek physician Hippocrates.

This document ended up in The National Archives when its owner was involved in a court case in the Court of Wards and Liveries. It was mixed up in their other papers and presented to the court as evidence.

Featured article

Record revealed

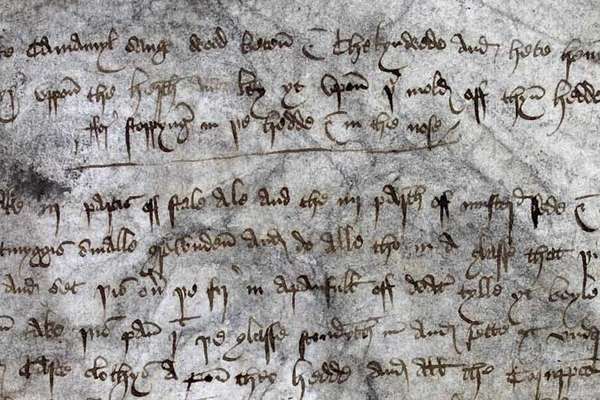

A medieval cold and flu remedy

Stale ale, ground nutmeg and mustard seeds – would you try these medieval cures for headaches and congestion? They give surprising insights into global trade.