In pictures

Postwar Caribbean migration

Thousands of people migrated from the Caribbean in the second half of the 20th century. After ‘400 Years’ (as Bob Marley and the Wailers sang) under colonial rule, many West Indians sought better lives and to contribute to the UK. They often had to overcome significant barriers and prejudice.

Photograph from the Kingston Bakery Strike

- Date

- 29 November 1942 – 23 July 1943

- Catalogue reference

- CO 137/855/11

This image is from a file about a trade union dispute at W. E. Powell and Co. Bakers on 28 April 1943. It shows nearly 2,300 kilograms of wasted dough, lost to the floor of the bakery in Kingston, Jamaica, after workers walked out during the busy Easter period.

The photograph was filed alongside correspondence from the Governor of Jamaica, who requested urgent amendments to defence regulations, including the use of warships to intimidate workers.

Through the 1930s, people across the Caribbean had engaged in labour disruption to protest poor living conditions and low pay, a result of years of economic underdevelopment and wealth extraction by the colonial government. These calls for better treatment emerged alongside a demand for universal adult suffrage and eventually independence, which was won in 1962. Simultaneously, Jamaica became the 15th country to join the Commonwealth.

Photograph and letter from Dorothy Marguerite Blanchette

- Date

- 1945–1946

- Catalogue reference

- DE/K/C1-C25

Many international students won a British Council scholarship to study in the UK after the Second World War. One of them, Dorothy, travelled from St Kitts to London in 1945 to study at the Guildhall School of Music, specialising in the piano. This photo was attached to her application.

A letter Dorothy wrote provides an insight into her journey to Britain via Trinidad and New York, her experience studying and living in England, and the differences between St Kitts and London. She discusses visiting ‘beautiful and historical places’ including St Paul’s Cathedral and the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford-upon-Avon.

It notes that she found her experience in England ‘taxing’ at times, as it was difficult to compress her studies into a year and she disliked the cold and rain. Nonetheless Dorothy describes her time as ‘one of the fullest richest years of my life so far.’

List of skills of passengers on the SS Almanzora

- Date

- 3 December 1947

- Catalogue reference

- LAB 8/1499

In 1947, SS Ormonde and SS Almanzora docked in Liverpool and Southampton respectively. Both ships brought several hundred migrant passengers from the Caribbean.

After the Second World War, the British Ministry of Labour noted that the Caribbean faced a ‘serious problem of over population and underemployment’. This was partly due to large numbers of out-of-work ex-servicemen. Britain, meanwhile, had a labour shortage.

The Ministry of Labour worried about Caribbean migrants arriving without jobs or accommodation lined up. Before the Almanzora set sail, attempts were made to understand passengers’ professions and skills. Trades reported included shoemaker, mason and seamstress. Many passengers were returning to Britain having already worked there, some during wartime.

Despite their existing skills, many passengers faced discrimination in the workplace and significant job downgrading.

The 1948 British Nationality Act

- Date

- 1948

- Catalogue reference

- C 65/6670

The British Nationality Act of 1948 came into force on 1 January 1949. Anybody born in Britain or in a British colonial territory now became a ‘Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies’ or ‘British citizen.’ As such, the nationality of people born in Britain and its colonies was made equal.

Some historians argue that this was an attempt to curb the growth of anti-colonial movements, increasingly pushing for independence. Others argue that it was intended to facilitate migration between Britain and what has been referred to as its ‘old dominions,’ meaning the white settler-colonies of Canada, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.

The increased flow of migrants from Africa, Asia and the Caribbean led to growing calls for immigration control throughout the 1950s (particularly after the Nottingham and Notting Hill anti-Black riots), resulting in the Commonwealth Immigrants Act of 1962.

The Empire Windrush passenger list

- Date

- 1948

- Catalogue reference

- BT 26/1237/91

The Empire Windrush passenger list is one of The National Archives’ most celebrated documents. It marks the arrival of the iconic postwar ship carrying a largely Caribbean workforce, eager to contribute to what many saw as the ‘mother country.’

It lists the names of the 1,027 people (over 300 of them women) who arrived at Tilbury docks on 22 June 1948, a day now annually marked as ‘Windrush Day.’

The list itself actually gives the date of arrival as 21 June, which has led some historians to argue that the ship docked at night, and the passengers disembarked the next day. They would go on to play an invaluable role in rebuilding post-war Britain.

The rows of largely European surnames allude to the imposition of these names on many of the migrants’ ancestors during slavery, and speak to the entangled histories of Britain and the Caribbean.

'A West Indian in England' leaflet by HD Carberry and Dudley Thompson

- Date

- 1949–51

- Catalogue reference

- CO 875/59/1

Two years after the arrival of the Empire Windrush, the British government commissioned a Ministry of Information leaflet titled 'A West Indian in England'.

It was written by HD Carberry and Dudley Thompson, two law students at Oxford who both lived in the Caribbean for substantial periods of their lives. They were tasked with informing migrants what they should expect on arrival in ‘unknown and darkest England’.

It humorously highlights unfamiliar aspects of British culture such as ‘The English Reserve’, ‘The English Climate and its Functions’, ‘Queuing’, and ‘The English Pub’ (described as a ‘Poor man’s night-club’). It also reflects more challenging areas of life, describing discrimination in the workplace, and the colour bar.

Files at The National Archives include various drafts, suggested amendments and a planned distribution list for the leaflet.

Ministry of Labour communication about Wolverhampton union activity

- Date

- 1955

- Catalogue reference

- LAB 10/1400

Many arrivals from the Caribbean took up jobs in Britain’s public transport system and faced racist attitudes from coworkers, employers, and trade unions.

In September 1955, tension at the Wolverhampton Corporation Transport Department resulted in the calling of a ban on overtime by the Transport and General Workers’ Union, in protest at the number of staff of colour.

In a bid to protect overtime pay for white workers, the union requested the 68 workers of colour be reduced to 52. According to the Manchester Guardian, between 400 and 500 people were involved in the action. The union claimed they did not support a ‘colour bar’, but staff refused to work overtime for 18 days, until the company set a quota for employees of colour.

At the time, bus crews were averaging 21 hours of overtime a week, meaning any ban would disrupt the local service significantly for the local community.

List of West Indian clubs and associations

- Date

- 1959–1960

- Catalogue reference

- CO 1031/2545

Numerous West Indian clubs and associations were established across Britain in the post-war period, offering a space for migrants to socialise, engage in recreational activities, and sometimes to politically organise.

This list highlights the range of clubs set up throughout the country, from the West Indian Association in Bristol and the British Caribbean Association in Birmingham, to London's United Kingdom Inter-Racial Brotherhood.

The attached report discusses the benefits that such organisations provide for both individuals and the community, such as creating ‘lasting friendships’, ‘providing a platform for exchange of information and news of home’, and ‘replacing activities indulged in in the West Indies before migrating’.

The geographical span of clubs across the country shows the cities, towns, and villages migrants settled in, and the positive impact their community spaces created.

Police file on arrangements for Notting Hill Carnival

- Date

- 1967-1976

- Catalogue reference

- MEPO 2/10891

Postwar Caribbean migrants brought music, food and cultural influences with them to Britain. To foster a sense of community, celebrate Caribbean culture, and in retaliation to racist attacks, West Indian carnival-style events were founded. The Notting Hill Carnival was born.

This file focuses on the struggle to keep the carnival going – from policing arrangements to local complaints.

In 1976 locals petitioned to stop the event, triggering protests in response to protect it. One protest flyer issued the rallying cry, ‘We negotiate from a position of power, and this is certainly not the first time in the history of Carnival that we have had to put up a struggle to control the streets for the celebration.’

Notting Hill Carnival continues to thrive, and annually attracts over a million people on to the streets of Ladbroke Grove, West London.

Newspapers advertising the Black People’s News Service

- Date

- 1976

- Catalogue reference

- CK 2/1535

The 1970s saw the creation of a wave of newspapers including the West Indian World, the Caribbean Weekly Post and the Weekly Crusader. Such papers had sections on local and national news as well as music and sports, and promoted businesses, food sellers and events. They also signposted resources like the Black People’s News Service.

The United English Nationalist Party reported the Black People’s News Service to the Race Relations Board for offering housing, education and legal support only to Black people, claiming it contravened the Race Relations Act. These newspapers were collected as part of the Board's investigation. New adverts were printed and the committee recommended not to bring proceedings.

Newspapers serving the Caribbean and wider Black community continue to this day, driven by the need for an understanding safe space.

Featured article

The story of

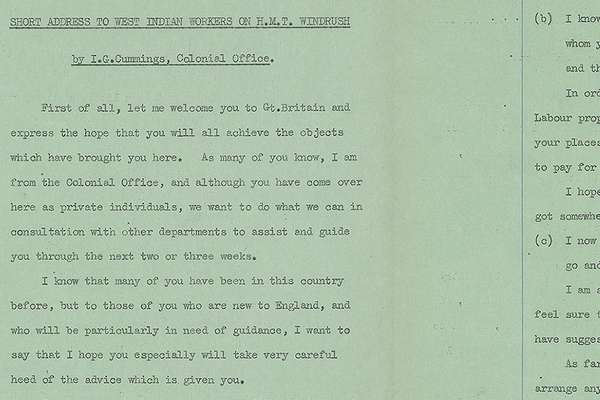

Ivor Cummings

Ivor Cummings (1913–1992) greeted the iconic arrival of the Empire Windrush at Tilbury in 1948. He became known as the 'gay father of the Windrush generation'.